Presented at The Developing Group 1 Oct 2005

Contents

This paper is in four parts:

- The love lab – John Gottman’s research

- Definitions of Contempt, Despise, Respect

- Comments from us

- Exercises

1. The love lab

Edited from Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell (Penguin/Allen Lane) 2005 Chapter 1, pages 18-47.

At the University of Washington a Psychologist, John Gottman studies married couples. The couples are sat down about five feet apart on two office chairs. They have electrodes and sensors clipped to their fingers and ears, which measure things like their heart rate, how much they are sweating, and the temperature of their skin. Under their chairs a “jiggle-o-meter” measures how much each of them moves around. Two video cameras, one aimed at each person, records everything they say and do.

How much do you think can be learned about Sue and Bill’s marriage by watching a 15 minute video tape of them disagreeing about their dog?

| Sue: | Sweetie! She’s not smelly … |

| Bill: | Did you smell her today? |

| Sue: | I smelled her. She smelled good. I petted her and my hands didn’t stink or feel oily. Your hands have never smelled oily. |

| Bill: | Yes sir. |

| Sue: | I’ve never let my dog get oily |

| Bill: | Yes sir, she’s a dog. |

| Sue: | My dog has never gotten oily. You’d better be careful. |

| Bill: | No. You’d better be careful. |

| Sue: | No. You’d better be careful…don’t call my dog oily, boy. |

Can we tell if their relationship is healthy or unhealthy? I suspect that most of us would say that Bill and Sue’s dog talk doesn’t tell us much. It’s much too short. Marriages are buffeted by more important things, like money and sex and children and jobs and in-laws, in constantly changing combinations. Sometimes couples are very happy together. Some days they fight. Sometimes they feel as through they could almost kill each other, but then they go on vacation and come back sounding like newly weds. In order to “know” a couple, we feel as though we have to observe them over many weeks and months and see them in every state. To make an accurate prediction about something as serious as a future of a marriage it seems that we would have to gather a lot of information and in as many different contexts as possible.

But John Gottman has proved that we don’t have to do that at all. Since the 1980s, Gottman has brought more than 3,000 married couples into a small room in his “love lab”. Each couple has been videotaped and the results have been analyzed according to something Gottman dubbed SPAFF (for specific affect), a coding system that has 20 separate categories corresponding to every conceivable emotion that a married couple might express during a conversation. Disgust, for example is 1, contempt is 2, anger is 7 defensiveness is 10, whining is 11, sadness is 12, stonewalling is 13, neutral is 14, and so on. Gottman has taught his staff how to read every emotional nuance in people’s expressions and how to interpret seemingly ambiguous bits of dialogue.

When they watch a marriage videotape, they assign a SPAFF code to every second of the couple’s interaction, so that a 15-minute conflict discussion ends up being translated into a row of eighteen hundred numbers — nine hundred for the husband and nine hundred for the wife. Then the data from the electrodes and sensors is factored in, so that the coders know, for example, when the husband’s or the wife’s heart was pounding or when his or her temperature was rising or when either of them was jiggling is his or seat, and all of that information is fed into a complex equation.

On the basis of those calculations, Gottman has proven something remarkable. If he analyzes an hour of a husband and wife talking, he can predict with 95 percent accuracy whether that couple will still be married 15 years later. If he watches a couple for 15 minutes his success rate is around 90 percent. Recently, a professor who works with Gottman names Sybil Carrere discovered that if they look at only three minutes of a couple talking, they could still predict with fairly impressive accuracy who was going to get divorced and who was going to make it.

One of his findings is that for a marriage to survive, the ratio of positive to negative emotion in a given encounter has to be at least 5 to 1. On a simpler level, though, what Gottman is looking for is a pattern in Bill and Sue’s marriage, because a central argument in Gottman’s work is that all marriages have a distinct pattern, a kind of marital DNA that surfaces in any kind of meaningful interactions. This is why Gottman asks couples to tell the story of how they met, because he has found that when a husband and wife recount the most important episode in their relationship that pattern shows up right away. Gottman says “When I first started doing these interviews, I thought maybe we were getting these people on a crappy day. But the prediction levels are just so high, and if you do it again, you get the same pattern over and over again.”

Gladwell uses the analogy of what people in the world of Morse code call a fist. Morse code is like speech. Everyone has a different voice. So during World War II, even when the British couldn’t understand what was being said because it was encoded, it didn’t necessarily matter, because before long, just by listening to the cadence of the transmission, the interceptors began to pick up on the individual fists of the German operators, and by doing so, they knew something nearly as important, which was who was doing the sending.

The key thing about fists is that they emerge naturally. Some part of the operator’s personality appears to express itself automatically and unconsciously in the way they work the Morse code keys. The other thing about a fist is that it reveals itself in even the smallest sample of Morse code.

What Gottman is saying is that a relationship between two people has a fist as well: a distinctive signature that arises naturally and automatically. That is why a marriage can be read and decoded so easily, because some key part of human activity has an identifiable and stable pattern. Predicting divorce, like tracking Morse Code operators, is pattern recognition.

“People are in one of two states in a relationship,” Gottman went on. “The first is what I call positive sentiment override, where positive emotion overrides irritability. It’s like a buffer. Their spouse will do something bad and they’ll say, ‘Oh, he’s just in a crummy mood.’ Or they can be in negative sentiment override so that even a relatively neutral thing that a partner says gets perceived as negative. In the negative sentiment override, people draw lasting conclusions about each other. If their spouse does something positive, it’s a selfish person doing a positive thing. It’s really hard to change those states, and those states determine whether when one party tries to repair things, the other party sees that as repair or hostile manipulation. For example, I’m talking with my wife and she says, ‘Will you shut up and let me finish?’ In positive sentiment override, I say, ‘Sorry, go ahead.’ I’m not very happy, but I recognise the repair. In negative sentiment override, I say, ‘To hell with you, I’m not getting a chance to finish either. You’re such a bitch, you remind me of your mother’.”

Gottman tracks the ups and downs of a couple’s level of positive and negative emotion, and he’s found that it doesn’t take very long to figure out which way the line on the graph is going. “Some go up, some go down,” he says. “But once they start going down, toward negative emotion, 94 percent will continue going down. They start on a bad course and they can’t correct it. I don’t think of this as just a slice in time. It’s an indication of how they view their whole relationship.”

The Importance of Contempt

Gottman has discovered that marriages have distinctive signatures, and we can find that signature by collecting very detailed emotional information from the interaction of a couple. But there’s something else that’s very interesting about Gottman’s system, and that is the way in which he manages to simplify the task of prediction. Untrained people looking at these tapes do no better than chance in predicting the outcome of a marriage from a discussion filmed 15 years earlier. Interestingly the tapes have been shown to 200 marital therapists, marital researchers, pastoral counsellors, and graduate students in clinical psychology and none of them was any better. The group as a whole guessed right 53.8 percent of the time. The fact that there was a pattern didn’t much matter. There were so many other things going on so quickly in those three minutes that they couldn’t find the pattern.

Gottman, however, doesn’t have this problem. He says he can be in a restaurant and eavesdrop on the couple one table over and get a pretty good sense of whether they need to start to thinking about hiring lawyers and dividing up custody of the children. How does he do it? He has figured out that he doesn’t need to pay attention to everything that happens. He has found that he can find out much of what he needs to know just by focusing on what he calls the Four Horsemen: defensiveness, stonewalling, criticism, and contempt.

Even within the Four Horsemen, in fact, there is one emotion that he considers the most important of all: contempt. If Gottman observes one or both partners in a marriage showing contempt toward the other, he considers it the single most important sign that the marriage is in trouble. Contempt is qualitatively different from criticism. Criticism is a condemnation of a person’s character and they are going to respond defensively to that. That’s not very good for problem solving and interaction. But contempt is a statement made from a superior plane. It’s trying to put the other person on a lower plane. It’s hierarchical.

Gottman has found that the presence of contempt in a marriage can even predict such things as how many colds a husband or wife gets; in other words, having someone you love express contempt toward you is so stressful that it begins to affect the functioning of your immune system. “Contempt is closely related to disgust, and what disgust and contempt are about is completely rejecting and excluding someone from the community. The big gender difference with negative emotions is that women are more critical, and men are more likely to stonewall. We find that women start talking about a problem, the men get irritated and turn away, and the women get more critical, and it becomes a circle. But there isn’t any gender difference when it comes to contempt.” If you can measure contempt, then all of a sudden you don’t need to know every detail of the couple’s relationship.

I think that this is the way that our unconscious works. When we leap to a decision or have a hunch, our unconscious is doing what John Gottman does. It’s sifting through the situation in front of us, throwing out all that is irrelevant while we zero in on what matters.

And the truth is that our unconscious is really good at this, to the point where thin-slicing often delivers a better answer than more deliberate and exhaustive ways of thinking. Gottman looks closely at indirect measures of how the couple is doing: the telling traces of emotion that flit across one person’s face; the hint of stress picked up in the sweat glands of the palm, a sudden surge in heart rate; a subtle tone that creeps into an exchange. Gottman comes at the issue sideways, which, he has found, can be a lot quicker and a more efficient path to the truth than coming at it head-on.

What people say about themselves can be very confusing, for the simple reason that most of us aren’t very objective about ourselves. Gottman doesn’t waste any time asking husbands and wifes point-blank questions about the state of their marriage. They mightlie or feel awkward, or, more important, they might not know the truth. “Couples simply aren’t aware of how they sound” says Sybil Carrere. “We play back the videotape to them and then we interview them about what they learned from the study. I would say a majority of them said they were surprised to find out either what they looked like during the conflict discussion or what they communicated during the conflict discussion.”

Not long ago, a group of psychologists reworked the divorce prediction test that people found so overwhelming. They took a number of Gottman’s couples videos and showed them to nonexperts — only this time, they provided the raters with a little help. They gave them a [short] list of emotions to look for. They broke the tapes into 30-second segments and allowed everyone to look at each segment twice, once to focus on the man and once to focus on the woman. This time around, the observers’ ratings predicted with better than 80 percent accuracy which marriages were going to make it.

For another article on this site that references John Gottman’s research see Modelling Conflict.

If you want more background, you can read a transcript of a talk by John Gottman, “The Mathematics of Love”.

2. Definitions

Etymology: From the Latin ‘to forcefully despise’.

Despise

Etymology: From Latin ‘to look down on’.

Respect1. A feeling of appreciative, often deferential regard; esteem. 2. The state of being regarded with honour or esteem. 3. Willingness to show consideration or appreciation.

Etymology: From Latin ‘to look more at’.

3. Comments on the extract from Blink

1. After 20 years Gottman is an expert at observation and pattern recognition. Novices can be taught to get pretty good results by following rules and being told what to pay attention to and what to ignore but it’s the tricky 20 or so percent that don’t fit the norm that are beyond a novice. (This is a confirmation of the Dreyfus and Dreyfus ‘Novice to Expert’ model.)

2. Gladwell isn’t saying that humans do at an unconscious level what Gottman’s mathematical equations do. Current research shows that brains in an area of competence do not work top down (i.e. by applying rules and models to a context) and they are not information processors (i.e. they do not run algorithms), they are holistic pattern recognisers. We can perform thin-slice pattern recognition but only after we have experienced enough situations to be able to recognise relevance and significance so that a small part of the pattern can trigger the whole.

3. Relationships have a fist, or a signature, because they are in dynamic equilibrium. That is, a pattern is maintained over time while adapting to changing circumstances.

4. Gladwell’s description of the Morse Code fist and marriage signatures are examples of the fractal nature of human behaviour. We have used other words to say the same thing: “People can’t stop being themselves.” This leads us away from traditional models of the organisation of the human psyche. In our model there can be no ‘real’, ‘false’, ‘true’, ‘hidden’, ‘whole’ selves. Of course individuals can experience themselves as real, false, etc. — that’s their prerogative. But to start from the position that there are true and false selves is an unnecessary imposition of many theories of mind. This is important because whether it is acknowledged or not, a therapist’s theory of mind will inevitably determine the direction of therapy.

5. It’s our contention that one way to get to the pattern from a small number of examples is to take a symbolic perspective. In fact, we suggest that this is one definition of symbolism. When we say something is symbolic we mean that the example, the instant, is representative of a larger pattern. The whole is reflected in the part.

6. Gottman’s negative and positive emotion override can be viewed from a systemic vantage point as escalating and dampening feedback loops. [You see why we avoid the terms ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ because technically Gottman’s negative emotion override is an example of a positive feedback loop, and vice versa!] When Gottman says “They start on a bad course and they can’t correct it” he is saying the escalating pattern of the relationship is so well established that it fuels itself. Systemically speaking, there are only two things that can change an escalating pattern once it has started: dissolution of the system (relationship in this case) or the triggering of a dampening, self-sustaining feedback loop that establishes a new equilibrium (and therefore a new kind of relationship).

7. There is a nice bind to contempt. Once we have felt contempt, how do we change that perspective? Changing it likely entails admitting being wrong about the person (“I misjudged them.”). And what does that say about us? Once we have hoisted ourselves onto the high horse of contempt, how do we get down? Sometimes a jolly good fall will do it, but that’s painful and often public. It’s a rare person who can dismount gracefully when emotions are high.

4. Exercises

We designed the following exercises with appreciation to David Grove for introducing us to many of the ideas on which these activities are based.

NOTE: These are awareness-raising activities. Where you are in a Facilitator role your job is to facilitate the Explorer to self-model, you do not have a contract for change work.

Exercise 1: Where is your sense of ...

This is an awareness activity. While it can be done alone it is best done in a group of four to six so that the results can be compared.

a) Each person divides a plane sheet of paper into 9 with each square labeled as:

| 1. | 2. | 3. |

| 4. | 5. | 6. |

| 7. | 8. | 9. |

b) Either:

Each person reads the instructions, identifies the locations and and draws their sketches in the relevant box.

Or preferably:

One person reads out the instructions s-l-o-w-l-y and gives the others time to locate each of their answers in their body or perceptual space and then draw their sketches in the relevant box.

NOTE: Some people prefer to locate and draw one at a time, others prefer to locate all nine and then draw them all. Or you can compromise and do them in three sets of three. You will just have to experiment.

The context is right now with a current partner or a significant other.

| Guide says (use only these words): | |

| 1. I | In the context of your partnership, where is your ‘I’? |

| 2. me | Where is your ‘me’? |

| 3. myself | Where is ‘myself’? |

| 4. us | In the context of your partnership, where is ‘us’? |

| 5. we | Where is ‘we’? |

| 6. our | Where is ‘our’? |

| 7. -> you | When your partner says ‘you’, where does that ‘you’ go? |

| 8. you -> | When you say ‘you’ to your partner, where does that ‘you’ seem to go? |

| 9. -> you (plural) | When someone else says ‘you’ about the partnership, where does that ‘you’ go? |

c) Reflect on your nine sketches – what do you learn from the way you experience these nine aspects of yourself and relationship?

d) Compare sketches – notice any patterns or distinctions.

NOTE: While most of us experience I, Me, Myself, You somewhere inside or nearby their body. There is usually much more variation in how we experience Us, We, Our, You (partnership). Common ways people symbolise these experiences are to use:

Location & relative distance (see our article on Proximity and Meaning)

Relative size

Figures touching or not

Inside or outside a container/boundary

Direction/facing (in front/behind)

Perspective from which drawing is done.

Sided-ness (left or right)

Firmness/Thickness of pen/pencil lines in the drawing.

Colour.

Exercise 2: The Respect – Disrespect – Contempt continuum

John Gottman’s research shows the amount of respect/contempt is a predictor of the longevity of a relationship. Gottman says 94% of couples, once they start on the contemptful road, can’t get off.

We suggest that one of the reasons is that they simply don’t know when they are being contemptful.

By doing this activity you can raise your awareness of how you experience respect/contempt. The aim is for a self-feedback loop is established so that it is clear as soon as either party starts to move toward the disrespect-contempt end of the continuum.

In a pair: Explorer and Facilitator.

The context your relationship with your current partner or a significant other.

a) Explorer:

- Use the context of your partner or a significant relationship.

- Assume that Respect – Disrespect – Contempt lie on a continuum.

- Imagine two lines on the floor that represent the continua of:

b) Explorer identifies two places on each continuum:

– One that symbolises the most respect/least contempt they have experienced with that person.

– The other, the least respect/most contempt.

c) For each place, Explorer stands on continuum and is facilitated (preferably with Clean Language) to identify the (visual, auditory and/or feeling) signals that let them know how they experience:

You — Contempt —> Partner

When you are disrespecting or contempting your partner, how do you know you are disrespecting or contempting them?

You — Respect —> Partner

When you are respecting your partner, how do you know you are respecting them?

You <— Contempt — Partner

When your partner is disrespecting or contempting you, how do you know they are disrespecting or contempting you?

You <— Respect — Partner

When your partner is respecting you, how do you know they are respecting you?

The aim is for the Explorer to identify four signals/knowings.

NOTE:

The signals that you are being respectful / contemptful to them may be a combination of:

– Their reaction

– Your signals after their reaction

Interior – Your signals

Exercise 3 - Part 1

In pairs, an Explorer and a Facilitator. 15 minutes in each role. 30 minutes in total.

The context your relationship with your current partner or a significant other.

NOTE: If you are bold, you might like to do this activity with your partner. You can either facilitate each other one at a time, or both of you could jointly be the Explorer – with or without a Facilitator.

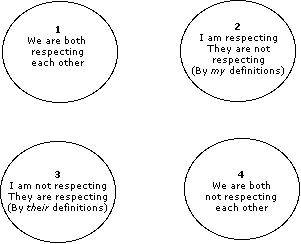

a) Explorer locates four spaces where they would like them to be, one for each:

b) Explorer stands in space 1 and nonverbally gets a sense* of what this experience is like.

c) Explorer moves to space 4 and nonverbally gets a sense* of what this experience is like.

d) Explorer moves to space 2 and is asked:

How do you know you are respecting them?

How do you know they are not respecting you?

e) Explorer moves to space 3 and is asked:

How do you know you are not respecting them (by their definition)?

How do you know they are respecting you (by their definition)?

* If you have the time this sense can be developed in a metaphor using Clean Language.

Exercise 3 - Part 2

a) Explorer returns to space 3.

Facilitator asks Explorer:

A. When you are disrespecting them, what needs to happen for you to respect them — by their definition?

B. And if that cannot happen, what would like to have happen?

b) Explorer returns to space 2.

Facilitator asks Explorer:

C. When they are disrespecting you what needs to happen for them to respect you?

D. And if that cannot happen, what would like to have happen?

c) Explorer moves to a fifth space, outside of the other four.

Facilitator asks Explorer:

And what have you learned?

And what difference will that make?

Exercise 4

In pairs, an Explorer and a Facilitator 20 minutes in each role. 40 minutes in total.

a) Explorer sketches two pictures or metaphors, one for each of —

A When you are respecting someone.

B When they are not respecting you.

b) Facilitator uses exactly the following instructions and questions:

1. Place that [B] where it needs to be.

Place that [A] where it needs to be in relation to that [point to B].

[with Explorer at A:]

And where would you like me to be?[Facilitator moves there]

2. Are you in the right space there?

Is that [point to B] in the right space there?

Is this the right distance between you and [point to B]?

[If not, have Explorer move A and/or B until they are just right.]

3. And what do you know from this space here [A]?

And what do you know from this space here about there [point to B]?

And is there anything else you know from this space here?

And find another space to go to. [The explorer moves to C.]

4. And what do you know from this space here [C]?

And what do you know from this space here about there [point to B]?

And what do you know from this space here about there [point to A]?

And is there anything else you know from this space here?

And find another space to go to. [The explorer moves to D.]

5, 6 and 7. [Repeat step 4 for spaces D, E and F (or until the time runs out).]

8. Return to space of A:

And what do you now know?

And what difference will that make?

Exercise 5: What do you do when you can’t both have what you want?

- What they want = X.

- Where they are now in relation to what they want = I.

- What their partner wants = Y

Where their partner is in relation to what they want = P

1. Explorer starts in I.

Facilitator asks:

- And what do you know from here about X?

- And what do you know from here about the you who wants X?

- And what do you know from here about Y?

And what do you know from here about P who wants Y?

Then:

Move to there [point to P]

2. [Explorer moves to P]

- And what do you know from here about Y?

- And what do you know from here about the P who wants Y?

- And what do you know from here about X?

And what do you know from here about the I who wants X?

Then:

Find a space that knows about the space between X and Y.

3. [Explorer moves]*

- And what do you know from here about the relationship between the X and Y?

And is there anything else you know from here?

Then:

Find a space that knows about the space between P and Y.

4. [Explorer moves]

- And what do you know from here about the relationship between the X and Y?

And is there anything else you know from here?

Then:

Find a space that knows about the space between the P that wants Y, and the you who wants X.

5. [Explorer moves]

- And what do you know from here about the relationship between that P and that you?

And is there anything else you know from here?

Then:

Find a space that knows about the space between the you that wants X, and X.

6. [Explorer moves]

- And what do you know from here about the relationship between that you and X?

And is there anything else you know from here?

Then:

Find a space that’s outside or beyond or above all of this.

7. [Explorer moves]

- And what do you know from here about all of that [gesture to all eight spaces]?

And is there anything else you know from here?

Then:

Return to your starting space.

8. [Explorer returns to I]

- And what do you know from here now?

- And what difference does knowing that make?

* sample configuration: