Working definition

A clean conversation is a dialogue that clearly expresses your intention while at the same time gives the other person the maximum opportunity to answer or respond without the imposition of your metaphors and assumptions.

A clean conversation differs from the use of Clean Language in a therapeutic setting because:

For example, in a clean conversation we can presuppose the laws of physics apply in a way we cannot in a metaphor landscape.In an everyday setting it is clean-ish for:

A police officer to ask, “Who was driving the car?” on the presupposition that the car wasn’t driving itself.

A person to ask their spouse, “What do you want for dinner tonight?” when they are about to start cooking the evening meal.

We will use the term ‘clean-ish’ when (given the context and intention of the speaker) the communication is towards the clean end of the clean continuum. Clean-ish is deliberately not a precise term.

The Clean Continuum

‘Clean’ is a continuum. Philip Harland once suggested it ran from ‘pristine’ to ‘filthy’ with ‘grimy’ somewhere in between. In

‘Whose map is it anyway?’ [Link available soon] Phil Swallow and Wendy Sullivan suggest that the continuum runs from 100% of the client’s map to 100% of the facilitator’s map. A waiter saying “Would you like anything else, sir?” is cleaner than “Can I get you a dessert?” because it leaves the customer freer to specify what they would like, without having to consider whether they want a dessert at all.

Whether a question or statement is clean depends on the language used in the context. Whether a conversation is clean also depends on the intention of the speaker. It is possible to ask perfectly clean questions with the intention to manipulate.

Which of the following are more or less clean?:

I think you should consider it.

Have you considered it?

I’d like you to consider it.

I’d want you to consider it.

Would you consider it?

Could you consider it?

Can you consider it?

You should consider it.

You must consider it.

You have to consider it.

You need to consider it.

You may consider it.

You can consider it.

You might consider it.

If I were you, I would consider it.

If you don’t consider it you’ll be sorry.

To remain towards the clean-ish end on the continuum it is not necessary to overtly state your intention, but it should be obvious from what you say. For example:

A: “What are you doing tomorrow?”

is a fairly clean everyday question. It would form part of a clean conversation provided the questioner’s intention is simply curiosity about the person’s actions tomorrow. However, let’s assume the conversation continues:

B: “Oh nothing.”

A: “Good, then you can take me to the doctor.”

In this case, although A’s original question was clean-ish A’s intention was not clear and therefore this is not a clean conversation. To have made it a reasonably Clean Conversation, ‘A’ would have needed to begin by saying something like:

A: “I need to go to the doctor’s tomorrow. Would you be willing to take me?”

The degree to which a communication is clean always depends on the context and the accompanying nonverbals. However, voice tone, facial expression and the like are not easy to describe on paper.

A clean conversation is not about the goodness or the value of what is said, rather, as the definition implies, it is about two things:

1. Acknowledging and working within another person’s logical and metaphorical constructs. This requires you to set aside your own metaphors and perceptual space while you are discussing their views, e.g.

A person states “I understand your proposal perfectly.” Rather than replying “Great, it’s nice to have you on board,” it’s cleaner to say “I’m pleased you understand, and what is your opinion of my proposal?”.

A clean-ish reply to the manager who says, “I think I’m going to have to go down with my ship” might be “Would you like some ideas about staying afloat, captain?”.

2. Making your intention clear (sometimes called ‘being straight’) e.g.

Saying “I want to get this done my way and I’m not interested in your ideas. Will you help me?” is clean even if it is autocratic.

Saying to your partner “I want a quiet night in” when you have secretly organised a surprise party for them, might be loving but it is far from clean.

Manipulation is keeping your intention hidden — even if it’s in another’s best interest!

And remember…

A clean conversation only requires one of the parties to maintain an intention to relate to the other in a clean-ish way.

‘Clean’ is not the same as ‘soft’. Softeners are words and phrases which make it easier for the listener to hear your opinion. They take the edge off of a potentially unpalatable point:

“Would you mind considering a contribution to this worthy cause?” is softer than “I’d appreciate you making a donation,” but it is not as clean.

‘Clean’ is not the same as ‘open’. In fact there are four variations:

| Clean and Open | Clean and Closed |

| Not clean and Open | Not clean and Closed |

Characteristics of a clean conversation

Being clean in everyday conversations requires a high degree of self-awareness. To hold a clean conversation you need to be able to

1. Maintain a partial meta (mindful) position during the conversation.

Being clean-ish is an active process that requires constant vigilance to prevent the default tendency to impose a perspective. Cleanness requires a conscious desire to remain clean throughout the conversation.

2. Make your internal context explicit.

This includes your intention, the source of the content and the background to your thinking. To do this in the moment you must know your intention, the source and the background, and be able and willing to express them clearly.

3. Align your metaphors and perceptual space with theirs.

You will need to: be aware when you/they are using conceptual, sensory or symbolic language; listen for their embedded/implicit metaphors; make your gestures and Lines of Sight congruent with their perceptual space.

4. Recognise and reference background logic in your and their statements.

This includes presupposition, assumption, entailments, inherent logic [see below].

5. Recognise and keep perceivers separate (especially yours and theirs).

6. Have clear distinctions between:

| Who is it for? | You / Them / Both of you / Others [see below] |

| What is it for? | Change / Modelling / Information Gathering |

| What kind of information? | What you observe / everything else Sensory description / everything else Opinion / everything else |

Example

A. “Oh, the rubbish is piling up.”

Some possible intentions of A:

i. I want you to notice what I have just noticed.

ii. I was just expressing myself [thinking out loud].

iii. I want you to take out the rubbish.

iv. I want you to pay attention to me [likely out of awareness].

Some possible clean-ish responses by B:

i. So it is.

ii. [No response.]

iii. When you say ’Oh, the rubbish is piling up’ like that, I hear it as an instruction for me to take the rubbish out. Is that the case?

iv. I so appreciate the way you notice these things (assuming you do).

How to have a clean conversation

(Compared to classic Clean Language) Use:

- Ordinary tonality

- Reduced syntax

- Selective repeating back

- Less classically clean questions

- Less: Where?, Like what?, Come from?

- More traditional questions, e.g.

And what would you like to have happen? => What would you like?

And what happens just before? => What happened before?

And is there anything else about that? => Anything else/Anything more?

- More direct, e.g.

- More use of tenses (maintaining their timeframe)

- More references to yourself, e.g.

- More presupposition about the physical world:

Four kinds of conversation

All conversations a have purpose – they can be considered for someone. Who that someone is will determine the kind of clean conversation required. While conversations have a back-and-forth nature, if we use the conduit metaphor to imagine that information goes from a source to a target, they can also have a direction.

These common purposes/directions occur when the conversation is principally for:

1. Them, e.g. teaching, giving directions.

2. You, e.g. learning, getting directions, information gathering.

3. Both, e.g. negotiation, exchange of information.

4. Others, e.g. customer requirements for passing along to a technology

department; newspaper reporter gathering information for readers;

jointly planning a training; lawyer questioning witness in front of jury.

Three kinds of relationship

When conducting a clean conversation, you also need to take into account when the relationship is:

Asymmetrical – You or they are in a position of greater authority, responsibility, knowledge, experience.

Symmetrical – You are peers or colleagues.

Symbiotic – It is mutually dependant, e.g. customer and supplier, police interviewer and a cooperative witness.

Combining the ‘Four Purposes/Directions of a Conversation’ with the ‘Three Kinds of Relationship’ could result in a 4 x 3 grid with examples of each of the 12 combinations.

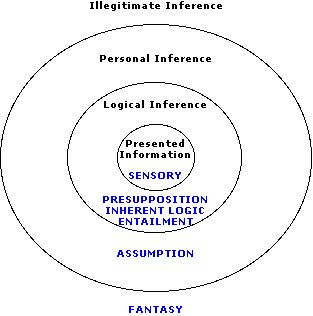

Degrees of inference

Starting at the centre and working outwards, the following diagram illustrates descriptions that are less and less clean (modified version of the model originated by Caitlin Walker, 2002):

We define our added distinctions as follows:

| Sensory | Observable behaviour (This can also include internal experience described in sensory terms by the person experiencing it. Many of these descriptions will actually be implicit metaphors) |

| Presupposition | What needs to be true for a sentence to make sense. |

| Inherent Logic | Inferring typical properties of an object or process. |

| Entailment | An effect that logically follows from an event or situation. |

| Assumption | A logical inference that requires the inclusion of information beyond the scope of what has been presented. |

| Fantasy | Imaginative inference. |

Being Clean Requires Self-Awareness

A pragmatic way to consider where meaning resides in a communication is to adopt the NLP refrain: ‘The meaning of your communication is the response it elicits’. While this refers to the person listening to what you say, it also includes your response to your own words.

Because we automatically respond to hearing our self say something, this response can be used as a monitor of cleanness. For many, a clean communication feels different. For example, while planning this day, James said to Penny:

“Shall we work to a theme or have a menu of items?”.

Penny noticed that she became wary and defensive for no apparent reason. So she said:

“I’m having an ‘I don’t want to go there’ response. Is there anything behind your question?”

When James’ explored what was happening for him internally it became clear that he had not been fully aware of his feelings or that he had a ‘hidden intention’ – hence the communication was less than clean. When he restated his question it became:

“I’m in a dilemma deciding whether to work to a theme or have a menu of items. Would you help me get out of it?”

Once this was said he noticed a shift in his body: a slight release of tension in the neck, a relaxation in the stomach, and an opening and uplifting in the chest [Sensory description]

Unknowingly James’ original statement was setting Penny up to give her opinion which James could test against his own match/mismatch signals (the latter being the most likely!). He expected that this would help him decide and therefore get him out of the uncomfortable feeling of being in a dilemma.

Looked at in Transactional Analysis Game terms, James felt a Victim and wanted to be Rescued. However, Penny refused his invitation and so the Game never got started. As soon as James said the clean version, he not only felt different, he realised there were more than two alternatives and he no longer felt the need to make a decision, but could wait and see what happened as the planning progressed.

As you can probably see from this example, if you are not having clean conversations with yourself, this may be an indicator that you are self-deluding, -deceiving or -denying.

Applications

Some applications where a clean conversation could come in very handy are:

Using Clean Language in an everyday conversation.

Facilitating a group.

Cleaning up a technique, questionnaire, announcement, etc.

Making your position clear (disagreeing, asserting) — cleanly.

Information gathering (finding out what people want; customer requirements)

Relating (parent-child; teacher-student, etc.)

Interviewing (police, job, journalist, researcher).

Negotiating/Mediating

Clean Training:

- Clean-ish instructions

- Using multiple metaphors to describe/explain models

- Incorporating participant’s metaphors

- Using metaphor overtly as a teaching/revision aid

- Checking the meaning of a question.

Recommended reading:

Time to Think by Nancy Kline.

The Gentle Art of Verbal Self-Defence and any other books in this series by Suzette Haden Elgin.

Games People Play by Eric Berne has great examples of patterns of unclean communication and ways to respond therapeutically and socially.

Fierce Conversations by Susan Scott.

These notes were first presented at The Developing Group, 6 April 2005.