Presented at The Developing Group 3 Dec 2011

The Research Project

We have been approached to take part in a research project which will make use of Symbolic Modelling and Clean Language as a research methodology. The project in part seeks to understand how coachees evaluate their experience of coaching. Specifically, the research aims to gather information through interviews about how coachees evaluate an experience of being coached with one particular type coaching.

Since we had not used Symbolic Modelling and Clean Language (SyM/CL) as a methodology for facilitating interviewees to evaluate their experience we ran some trial interviews and recruited 21 members of the Developing Group to investigate the similarities and differences with ‘standard’ clean research interviewing.[1]

Others, notably Nancy Doyle and Caitlin Walker, have conducted clean interviews into the effectiveness of their work in organisations. Their evaluative interviews (discussed in Appendix A) are of a different kind to those to be undertaken in our project.

Below are some guidelines for anyone wanting to undertake a ‘clean evaluative interview’ (CEI).

Evaluative Interviewing

Evaluative interviewing can be distinguished from other types of interview by the content it aims to identify. In an evaluative interview we want to know the value the interviewee assigns to a particular experience, i.e how they assess, judge, gauge, rate, mark, measure or appraise what happened. While quantitative evaluations are useful, people often use more naturalistic, qualitative ways of assessing. We want to understand how people arrive at this kind of evaluation.[2]

We propose that Symbolic Modelling and Clean Language offers the academic and commercial research community new ways to identify and explore this kind of highly subjective phenomena.

Clean Interviewing

A clean evaluative interview is one that cleanly facilitates an interviewee to evaluate an experience they have had – and optionally to describe the process by which they arrived at that evaluation.

In a clean interview, the interviewer aims to supply as little content as possible, to make minimal assumptions about the interviewee’s experience, and to allow them maximum opportunity to express themselves in their own words. In particular, clean interviewers are keen that their questions do not presuppose ways of understanding the world. While many interview methods claim to do this, it is clear from transcripts that interviewers often unwittingly introduce content and presuppose ways of answering. Since they don’t know they are doing it many interviewers are blind to the effect they are having See Paul Tosey’s paper for excellent examples [3].

There are two distinctions that set apart a clean interview from other clean methods where change is the purpose: (a) the interviewer/modeller decides the topic or frame for the interview, usually in advance; and (b) the information gathered is used for a purpose unconnected, or loosely connected, to the interviewee.[4]

In a CEI it may not be possible to only use classic clean questions. At times a few bespoke or ‘contextually clean’ questions – ones based on the interviewee’s particular logic and the context within which the interview is conducted – will be needed.

While it not the aim of the interview, it is expected that the interviewee will benefit by greater self-understanding of their internal behaviour. That in turn may give them more flexibility with their external behaviour. In the work-life balance research for example, without it being suggested several of the managers interviewed reported that they had made adjustments to bring their lives more into balance as a result of the interview.[3]

The use of Symbolic Modelling and Clean Language as an interview / research / modelling methodology has been growing over the last ten years. The table below lists a number of ways a clean approach has been used in interviewing. While the method of interviewing cleanly needs to be adjusted to suit each context, the core process remain the same.[5]

| Type of Interview | Purpose of Interview |

| Critical incident interviewing | To gain a full description from people who observed or were involved in an event such as an accident or crime, e.g Caitlin Walker’s training police officers to interview vulnerable witnesses [trainingattention.co.uk link no longer available] |

| Evaluative interviewing | To evaluate an experience or to investigate the effectiveness of an intervention. And sometimes to describe the process of evaluating. |

| Exemplar modelling | To identify how an expert does what they do so expertly, e.g. our Modelling Robert Dilts Modelling. |

| Health interviewing | For patients to the describe their symptoms and/or their well-bring in their own words and metaphors, e.g. our training of specialist Multiple Sclerosis nurses. Also used for diagnosis or social health planning. |

| Journalist interviews | Information gathering for articles. |

| Market research interviewing | To seek the opinion and views of a person or group on a product or service e.g. Wendy Sullivan and Margaret Meyers’ work. |

| Modelling Shared Reality | To identify connecting themes, ‘red threads’, across a disparate group or groups. (The Modelling Shared reality process was developed by Stefan Ouboter and refined by others). |

| Phenomenological interviewing | For individuals to describe their first-person perspective of an experience, e.g. Work-Life Balance research conducted by University of Surrey and Clean Change Company. Download the report here and see note [3]. |

| Recruitment interviewing | To interview candidates for a position or for executive search. |

| Specification definition | To produce a specification of a role, process or competency. Used in benchmarking, needs analysis, customer requirements, etc. |

Symbolic Modelling

When using Symbolic Modelling the interviewee’s metaphors and internal process form a major part of the interview. The rationale for this emphasis is based on the the Cognitive Linguistic hypothesis that autogenic metaphors not only describe what people experience, they reveal how that experience is structured. Furthermore, it proposes that metaphor informs and mediates all of our significant concepts.[6]

A symbolic modeller facilitates the interviewee to self-model and to describe the results of that self-exploration. The interviewee is not led by being given criteria against which to evaluate. In a traditional interview the coachee-interviewee might be asked: “How do you rate the coaching in terms of ‘rapport’ (‘insights’, ‘challenge’, etc.)?” or “on a scale of 1 to 10?”. In a CEI the interviewee defines their own evaluative criteria through the process of self-modelling. This requires the interviewer to have the skill to pick out the criteria identified by the interviewee during the ongoing flow of description, explanation and narrative – and to facilitate an elaboration of the interviewee’s internal process.

Evaluating

To evaluate anything requires the comparison of two things: the comparison of an experience against a ‘standard’, ‘yardstick’, ‘ideal’, ‘criteria’ or some other measure. What gets compared with what can vary enormously from one person to another. For example, a coachee could evaluate a coaching session by comparing their feelings at the beginning and the end of a session; another by whether their expectations of the session were met; and yet another by whether they achieved their desired outcome after the session.

People will likely evaluate their experience as it happens. And they will often form an overall assessment afterwards. Daniel Kahneman has shown that our overall assessments are far from a simple summation of our moment-by-moment assessments. [7] For example, if you randomly ask people to assess how happy they are at that moment they often give significantly different answers to when they are asked for a general assessment for their happiness. Given that it would be impractical to keep interrupting a coaching session to question the coachee, we are left with identifying the coachee’s overall assessment sometime after the session.

Below are some examples of what coachees have used to measure their experience against:

| Coachee statement | Comparison |

| “The most powerful coaching I’ve had.” | Other coaching sessions |

| “I felt a big shift at the time.” | Their experience in the session |

| “I can now happily present to a room full of people.” | The outcome of the coaching |

| “I hoped I’d get unstuck and I have.” | Their expectations |

| “I was disappointed, everyone said they were so brilliant.” | Other’s opinions |

| “Overcoming the fear means I’m a different person.” | The consequences of the coaching |

Evaluating almost inevitably makes use of scales and scaling. Rarely is an evaluation of a complex experience such as coaching a digital or binary comparison. Most people have more subtle ways of evaluating than whether something is either good or bad, useful or a waste of time, etc. Instead, evaluation normally involves assessing ‘how much?’. How much of a good feeling? How much of an expectation was met? How much was achieved? To understand more about how people scale their experience we recommend our article, ‘Big Fish in a Small Pond: The importance of scale’, NLP News, Number 7, March 2004. cleanlanguage.com/big-fish-in-a-small-pond/

Key Distinctions

People evaluate without giving much thought to how they evaluate. They may not consciously distinguish between their evaluations and other aspects of their experience, and they may have little idea of the process they went through to arrive at an evaluation – until they are facilitated to consider that aspect of their experience.

To make sure the interview accomplishes its aim, the interviewer needs to vigilantly hold to the frame of the interview and keep a number of distinctions in the forefront of their mind. Below we describe the distinctions which we have found are key to gaining the maximum from a clean evaluative interview.

Types of information

People provide different types of information during the interview. They will describe what happened during the eventbeing evaluated, what were the effects of that event, and their evaluation of what happened. We call these the three E’s and hypothesise that in most cases it is the effects that are evaluated, rather than the event itself.

An interviewee may need to describe the event and its effects before they can recognise or focus on their evaluation:

The interviewee’s language provides clues to the type of information being described:

Events

- The coach listened to me.

- This happened, and that happened.

- I experienced x, y and z.

Effects

- The questions got me thinking in a new way.

- I took a step forward in my development.

- I realised I needed more sessions.

Evaluations

- I didn’t find it very useful.

- Afterwards I see I got a lot out of it.

- Wow, what a session!

Moreover, interviewees will often switch back and forth between event, effect and evaluation. The interviewer therefore has to be alert to the kind of information being presented to ensure that when the opportunity arises they direct the interviewee’s attention to evaluative information.

The Semantic Differential

In the 1950s Charles Osgood developed the semantic differential as a way to measure how people differentiate the meaning of a concept. Osgood and others used a large number of polar-opposite scales and found three recurring factors of affective meaning: evaluation, potency and activity. Further studies showed that these three dimensions were also influential in dozens of other cultures. Examples of these scales are:[8]

| Evaluation | nice-awful, good-bad, sweet-sour, helpful-unhelpful |

| Potency | big-little, powerful-powerless, strong-weak, deep-shallow |

| Activity | fast-slow, alive-dead, noisy-quiet, young-old. |

Osgood was studying ‘affective meaning’ which is a more general concept than our area of interest. However, how much a person is ‘affected’ will involve some kind of evaluation. So what of Osgood’s work can we apply to our study?

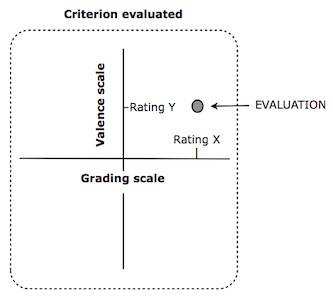

Not surprisingly, Osgood’s ‘evaluation scale’ is a vital sub-set of the evaluation process we want to model. Because we are already using ‘evaluation’ to refer to the whole process, we will borrow a term from chemistry – valence – to refer to this scale. Since no experience is intrinsically positive/negative or helpful/unhelpful, etc. our aim is to discover how the interviewee evaluates it, what they call it, and whether the evaluation involves degrees or graduations of valence.

‘Potency’ involves scales of amount and is therefore directly relevant to our study. For our purposes it is not clear that Osgood’s ‘activity’ scales are fundamentally different from potency scales since they both enable a person to grade or measure the amount of a quality or attribute. We propose combining them into a single ‘grading’ scale.

Note that using a ‘semantic differential’ involves the pre-selection of the word/concept to be evaluated; whereas, in a clean evaluative interview only the context is defined (in this case a coaching session). The interviewee selects whatever content they consider significant. We call the bits of content they select, the criteria.

To summarise, based on Osgood’s semantic differential and having studied how people express their evaluations in everyday language we propose that an evaluation involves four elements:

| Criterion | the quality used to make the assessment |

| Grading scale | a means of ranking or measuring the relative amount of the criterion |

| Valence scale | a judgement of the degree to which an experience is considered favorable/positive/good/valuable or unfavorable/negative/bad/valueless by the interviewee. (Note sometimes the entire scale is regarded as positive or negative) |

| Rating | the position on a grading or valence scale allocated to a particular experience of the criterion (X and Y on the diagram below) |

Evaluation can thus be depicted as:

The importance of ‘valence’ is illustrated by the coachee who said “I’d say my anxiety was 50% down.” We know the criterion (anxiety), the grading scale (percentage down), the rating (50), but without the valence we cannot know whether the coachee thought this was a good or a poor result (and it is vital to not make an assumption).

In fact the coachee said “and that’s a fantastic success.” This suggests a valence scale of amount-of-success and a rating of “fantastic”.

The following examples show how three interviewees’ language indicates the criterion, grading and valence scales, and rating thereof they used to make their evaluation:

- I valued the deep rapport.

- The coach wasn’t much help.

- I got the lasting effect I wanted.

| Criterion | Grading Scale | Rating | Valence Scale | Rating | |

| 1. | rapport | (depth) | deep | value | valued |

| 2. | the coach | help | not much | (unspecified) | (unspecified negative) |

| 3. | the effect | (duration) | lasting | wanted | got |

Content versus Process

A key distinction that is embedded in the above is the difference between the result of the interviewee’s evaluation and the way they arrived at that evaluation. This is the difference between the what and the how, the product and the process, the rating and the scale.

Timeframe

A coachee can make their evaluation during the session, immediately after, or much later. Coachees often report that their evaluations change over time and the length of time between the coaching session and the interview may be a factor. Therefore it may be important to find out when the evaluation was made and if it has changed. To complicate matters, during an evaluative interview the interviewee will inevitably reflect on their evaluation and they may change their evaluation as they self-model.[9]

It’s important to note that the above distinctions are to help the interviewer familiarise themselves with the common processes of evaluation. It’s vital in a CEI that the interviewee is modelled from their perspective. These distinctions cannot be introduced into a clean interview since an interviewee may not see the world this way. Our aim is to discover how each particular interviewee evaluates – regardless of how idiosyncratic that might be.

Overview of a Clean Evaluative Interview

The frame and what will happen to the output should be clearly stated at the outset of the interview.

Start with something very open, e.g. ‘How did it go?’ or ‘How was that [context]?’

Use ‘And is there anything else about …?’, ‘What kind of … ?’ and ‘How do you know?’ questions to invite the interviewee to describe their experience in more detail.

Direct the interviewee’s attention to their evaluative words. Listen for words like:

| good / bad useful / useless big / little impact helped slightly/moderately poor / rich over (e.g. overwhelm) too I got lots out of it. | extremely mainly detrimental deeply better / worse beneficial improved valuable / no value | (not) enough (in)sufficient (in)adequate (no) progress (not) helpful (un)satisfactory (un)acceptable (un)productive (not) worthwhile |

To help you develop an ear for evaluative words Appendix B shows examples from 40 people’s evaluation of their previous therapy/counselling.

- Develop the metaphor for the scale (or scales) the interviewee is using. Facilitate them to identify the attributes of the scale e.g. length, top, bottom, threshold, graduations, linear/nonlinear (without introducing any of these words).

- Pay attention to scaling indicated by the interviewee’s gestures. As soon as the interviewee starts to physicalise a scale with their gestures, use that description as a reference point. It makes it easier for the interviewee to explain and easier for the interviewer to understand.

- If it doesn’t happen spontanteously, ask location questions of where the scale is within the interviewees perception and where the rating is on the scale.

- At some point, focus the interviewee’s attention on their evaluation of a specific event and find out how they rate it, i.e. where they put their assessment of the event on their scale.

- If they use several scales, it is important to know the relative weighting. Spend more time on the one that is most important for the interviewee.[10]

- As new information emerges find out how it relates to the scale(s) already developed. The aim is to make the evaluation and the process of evaluating central to the whole interview.

- Once enough of the interviewee’s model has been elicited, recap it and check for congruence, e.g. for verbal and nonverbal “Yeses”.

- If time permits, check your modelling with another sample event

Tips

- The following analogy may help interviewers understand their role. The interviewee is like a film/theatre reviewer. The interviewer is like a journalist who has to write an account of the reviewer’s assessment of a film, including the process by which the reviewer came to that evaluation. While the criteria a coaching client uses to evaluate their experience will be different to the criteria used by a film critic, both go through an internal evaluation process to arrive at their conclusion.

- It is useful to know your own criteria for evaluating before you start doing this kind of research. It can reduce assumption, confirmation bias and the halo effect (unconsciously thinking that aspects of a person’s behaviour or way of thinking that are like yours have extra value).

- Consider using two interviewers. Both can track what has and hasn’t been covered and both can ensure the interview remains focussed and within the specified fame. Since both interviewers are modelling from the interviewee’s perspective it should seem like a single seamless interview. Hence once a Symbolic Modelling interview has started the interviewee is rarely bothered by an extra interviewer in the room.

- Given that the interview will be recorded, think in advance about how to take notes. The main purpose of note taking will be to remind you of the exact words the interviewee used to describe their evaluation, and as a check that you have covered the range of potential material available.

- Keep your nonverbals clean and use lots of location questions.

- Do not assume, ask! One person’s “4 star” rating may not be the same as another’s: “And 4 stars out of how many?”.

- Be careful of asking questions like, “What would you have liked instead?”. While this kind of question can help fill in gaps it also risks turning the interview into a change-work session; and that is definitely inappropriate in a CEI. Also, people’s evaluations are not always based on what they like, e.g. “I like things to be easy but when it wasn’t that’s when I got my breakthrough.”

- Bringing your experiences into the session would not be clean. If you want to offer the interviewee a comparison so they make distinctions, make sure you use something you know they have experienced e.g. “How was this session compared to (other coaching sessions you’ve had)?”

- Occasionally some people will evaluate on a digital or binary scale. For instance, evaluating a session as being ‘boring’ or ‘engaging’ could be like an on/off switch with no options in between. If so, what happens in the sequence of switching on and off is of great interest. Having said that, it is common for an apparent binary evaluation after a little consideration to reveal itself as an analogue scale.

- Although ‘And what’s that like?’ is often mistakenly used by novice symbolic modellers, in a CEI it may be useful. (David Grove’s original clean question, ‘And that’s […] like what?’, is used to invite a person to translate their conceptual or sensory description into a metaphor.) ‘And what was that like?’ is a clean question in that does not introduce content-leading information. It can be useful because it frequently invokes an evaluation, judgement or comparison, e.g.

Interviewee: The coach sat there quietly, blank-faced, he didn’t say much at all. Interviewer: And what was that like? Interviewee: It was really bad, well it’s horrible isn’t it, you know, like, I would say it was really hellish.

- An important evaluative word to be aware of is ‘important’ and other such words:

significant major critical decisive crucial essential valuable vital fundamental

- If something is ‘important’ it means it is ‘of consequence’ or ‘of value’ and is, or is close to being, a universal way people evaluate. As such it can be regarded as being a pretty clean concept to use. The word is not overtly metaphorical either, so while it is not classically clean (David Grove did not use it) it could be regarded as being contextually clean in an evaluative interview. Asking ‘What is important about that?’ is much cleaner than saying ‘What was useful/enjoyable/worked well?’; since ‘important’ doesn’t presuppose that what happened was viewed as positive or negative for the interviewee. (i.e. it does not assume a valence).[11]

- Don’t rush to ask questions like “How do you evaluate?” (even if the interviewee has used the word). It is a highly complex question that many people will not be able to answer except with generalities. Instead listen and watch for clues to the interviewee’s process. Use these to facilitate them to reveal bit by bit what and how they evaluate. Allow the distinctions of the interviewee’s evaluation process to emerge naturally in their own time.

Sample contextually clean questions

The following sample questions are included to give a flavour of the variety of questions you may find yourself needing to craft in order to ask as cleanly as possible about what the interviewee has said. Some of the questions may seem odd when read out of context; however during a SyM/CL interview they will likely make complete sense to the particular interviewee.

How do you know [their evaluation]?

What lets you know [their criterion] is happening?

How [their criterion] was it?

To what extent/degree did you [their criterion]?

How much [their evaluation] was it?

And the effect of that was?

What was important about that?

Is there anything else about [the session] that was important to you?

Is there anything else about [their evaluation] in relation to […]?

What determines where [their rating] is on [their scale]?

When [criterion or event identified as important] what happens to [evaluation]?

How many [name for graduations on their scale] are there?

Is there anything between X and Y on [their scale]?

When [one place on their scale], where is [higher/lower rating]? (e.g. And when ‘deep’ is there, where is ‘deeper’ that you were used to going?)

When this is [one end of the their scale] and this is [other end of their scale] where is [their evaluation of the session]?

Does that [gesture to nonverbal that marks out the scale] have a name when that’s [gesture to one end of the scale], and that’s [gesture to the other end]?

Does that [experience] relate to [gesture to an already explored scale] or not?

How was that session in relation to [their means of comparison]?

When it wasn’t [their evaluation] what kind of session was it?

When did you know it was [their evaluation]?

When did you [decide] it was [gesture to relevant place on their scale)?

When-abouts did you notice, that it was [their evaluation]?

Notes

1 The Developing Group provided a test-bed for establishing a methodology for clean evaluative interviewing. We set up interviews that resembled as closely as possible what will take place in the research project. We gathered feedback from the interviewee, the interviewer and an observer on how well the process worked – or not. We sought suggestions for improvements and things for interviewers to take into account. These notes have incorporated that learning. They also draw on the excellent handout Wendy Sullivan produced after the day.

2 In a video entitled ‘Individual Identity’, Baroness Professor Susan Greenfield describes how evaluative processes develop in children: youtube.com/watch?v=rcSSPTfEcJM

“You are most adaptable when you are very young, when you are unconditionally open to everything because you don’t have anything with which to evaluate the world. So you start off as a one-way street where you just evaluate it in terms of the senses and you unconditionally accept whatever comes in. …But the more experiences you have the more you will interpret what comes in in terms of what you’ve experienced already. So you shift from a sensory input of how sweet, how fast, how cold or how bright, to evaluating ‘What does this mean to me?’. And so we shift from noticing something not because they are noisy or bright or fast, but simply because they are your mother. And so you switch from senses to cognition. …Then we start to live in a world in which we are evaluating in much more subtle ways, much more personal ways, much less obvious ways, more cognitive ways, which gives you your unique take on the world. And that is constantly updating and changing.”

3 Tosey, Paul (2011) ‘Symbolic Modelling as an innovative phenomenological method in HRD research: the work-life balance project’, paper presented at the 12th International HRD Conference, University of Gloucestershire, 25–27 May 2011.

4 For more on the distinctions between interviewing and change-work see our article, What is Therapeutic Modelling?, ReSource Magazine Issue 8, April 2006.

5 Some of these are described in our article, Using Symbolic Modelling as a Research Interview Tool.

6 Evans, V., Green M., 2006. Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

Kövecses, Z. 2002. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M., 1980/2003. Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M., 1999. Philosophy in the flesh: the embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. Basic Books.

7 Kahneman, Daniel and Jason Riis, ‘Living, and Thinking about It: Two Perspectives on Life’ in Huppert, F.A., Baylis, N. & Keverne, B., The Science of Well-Being, 2007, pp. 284-304.

8 These examples are taken from Chapter 14, The Semantic Differential and Attitude Research, David R Heise in Attitude Measurement (edited by Gene F. Summers. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1970, pp. 235-253).

9 When it comes to analysing a transcript of an interview our Perceiver-Perceived-Relationship-Context (PPRC) model may be useful for classifying the source of the evaluation. For example:

| “I felt good” “The coach was quite cold” “Safety was an issue” “The room was very relaxing” | Perceiver Perceived Relationship Context |

10 There is a subtle link to a recent Developing Group topic – calibrating. Calibrating, as we use the term, involves the facilitator assessing whether what is happening for a client is working, or not. It is a moment-by-moment judgement: Is it likely that the client is getting something valuable, or potentially valuable from what’s happening? While interviewees may benefit from a research interview, this is not the aim. As long as the interviewee is ok with what is happening (and if there is any doubt it is best to check) interviewers have to use a different calibration to facilitators of change. They have to assess moment by moment: ‘Is the interview on topic’? and ‘Am I getting the kind of information required?’.

11 People often imbue the unexpected with import. Therefore listen out for clues such as: surprising, sudden, it just hit me, out of the blue, I wasn’t expecting that. These may indicate areas to explore further.

Appendix A: Other types of CEI

Nancy Doyle and Caitlin Walker of Training Attention have conducted clean interviews of the effectiveness of their work since 2002. Below James précises his conversations with them about how they conducted their evaluations.

The kind of evaluative interviewing undertaken by Training Attention is the diligent recording of the state of a system ‘before’ and ‘after’ and then comparing the two (or more) as a measure of the effectiveness of their work. The article that Nancy, Paul Tosey and Caitlin Walker wrote for The Association for Management Education and Development’s journal is an example of using clean interviews to explore and evaluate organisational change.*

This approach to evaluating an intervention has a similar but different aim to our evaluation project. We are focussing on the interviewee making an evaluation of a context that the interviewer was not involved in. Any ‘before’ and ‘after’ comparison is done by the interviewee not the interviewer.

Nancy Doyle a Chartered Occupational Psychologist has been at the forefront of evaluating the impact of interventions in organisations. Clean interviews have been used to evaluate all of Training Attention’s organisational work, starting with Nancy’s masters degree. This includes the Welfare to Work research published by the British Psychological Society in 2010 and 2011 (note this research focuses more on quantitative results).

Below are Nancy’s answers to James’ questions:

– What makes your evaluative interviews different from other types of (clean) interviews?

It is dirtier than other classically clean interviews. You don’t start with “And what would you like to have happen?” Instead you begin with a clear concept that you want the interviewees to describe. Then you can compare (by asking questions such as “Currently, the company is like what?”) the initial model of the organisation to subsequent models.

The purpose of the interview is for the interviewer to understand what is happening, as well as the client gaining insight. The interviewer is using clean questions to remove his/her interpretation from the output, but not to remove his/her influence on what the kind of output should be.

What protocols have you designed for conducting your evaluative interviews?

We email prompt-questions in advance. We then conduct interviews using the prompt questions and clean questions. This can be done on the phone.

What have you learned from your evaluative interviewing?

You can improve the quality of interviewing in research by teaching interviewers Clean Language. With the Welfare to Work clients, interviewers were trained in Clean Language and given a list of approximately 10 questions I wanted to know the answer to. They were instructed to only ask the prompt questions and when they needed to elaborate or clarify to only ask clean questions. This meant they were less likely to go ‘off piste’ or to start directing interviewee responses.

Caitlin Walker said that a question they were frequently asked is, “What research is being done in this field?” Luckily clean questions are themselves excellent research tools.

A key question they ask their customers is, “How do you know what you’re doing is useful?”. And they continually ask it of themselves. Evaluating the impact of their work is an ongoing challenge. Design and delivery are very different skills from those required for research and evaluation. This is not a problem unique to people who use clean approaches. Training Attention’s customers tell them that very little evaluation takes place even for large scale projects. Often projects begin without research into what people really want to have happen. Many projects end without meaningful feedback as to whether they have made any lasting difference. As a result sometimes today’s change processes become tomorrows problems.

Training Attention have a number of well-thought through, longer-term evaluations and case studies, including the effectiveness of:

- Diversity Training across 900 members of a Primary Care Trust

- Whole-system change in a secondary school

- Welfare to Work interventions

Peer coaching from primary to secondary school transition.

All have detailed evaluation reports. Michael Ben Avie who is connected with Yale University helped to evaluate the whole-school project.

Caitlin’s examples of evaluative interviewing generally involved three stages:

1. First build a relationship between the person and their experience. This can be achieved with question like:

– Currently, [context] is like what?

2. Then ask them to make an evaluation, e.g.

– What are you able to do differently?

– What’s the difference that made the difference in achieving or not achieving [project outcome]?

– And is there anything else that made a difference?

– How did that impact on you achieving [project outcome]?

– How well or not well is [context] working?

3. Follow that with a request for a desired outcome, e.g.

– How do you want [the group] to be?

During stage 1 the interviews start with a very broad frame until patterns in people’s attention emerge. Once a number of people have been facilitated individually or in small groups, common evaluation themes emerge e.g.

– Maintaining motivation

– The distance/closeness between members of a group

– The amount of feedback being given/received

– How well or not something worked.

At Liverpool John Moore University, seven themes were mentioned by 50% of the 45 people involved.

In stage 2, evaluation can be on a pre-defined scale e.g. 0-10 (where 10 could be ‘being able to work at your best’); or a personal scale, e.g.

– Uncomfortable – Comfortable

– Volume of arguments

– Feeling scared – Safe

– Level of aggressive behaviour.

The same external behaviour/circumstances will be evaluated by different people using different criteria. A peer’s behaviour could be evaluated by one person on a uncomfortable-comfortable scale, while another might use their degree of irritation.

If a person is unable to come up with their own evaluation criteria, they can be given a number of representative examples – these must cover a wide range.

As a minimum, people evaluate against their own (unconscious) desired outcomes or expectations.

Numerical evaluations are interesting but on their own they do not give much indication of how to use them to learn and improve things. For that you need reasons, metaphors and outcomes.

* Doyle, N., Tosey, P. & Walker, C. (2010). Systemic Modelling: Installing Coaching as a Catalyst for Organisational Learning, e-Organisations & People, Journal of the Association for Management Education and Development, Winter 2010, Vol. 17. No. 4. pp. 13-22. Download original article (PDF).

Appendix B: Examples of 40 people’s evaluations

Below are 40 examples of people’s evaluation of their previous therapy/counselling (with a sample of evaluative words underlined, not all statements contain indicators of evaluations).

Each person was asked one of the following questions:

What did you get from the therapy or counselling you’ve had?

What was most valuable about your previous therapy or counselling?

By studying the list you will enhance your ability to detect when a person’s language indicates they are making an evaluation. Each of these indicators could be the entry point into an exploration of the interviewee’s way of evaluating the therapy/counselling.

Notes:

- Not every answer has a clear evaluation (or the valence is unspecified); where not, no words are underlined.

- Some answers have an ‘implicit valence’ (e.g. in example 6, ‘integrative’ in the context of therapy or counselling is highly likely to have to have a positive valence). Of course, the interviewee’s nonverbals will make their evaluations clearer, but even so it is best to hold your suppositions lightly until there is clear evidence.

- I learned to relax and take in the surrounds. I found it calm and reflecting. It helped me challenge my assessment of myself.

- I’ve done loads of therapy. It’s helped me see clearly, focus on the big picture, have a sense of expanding into possibility where I feel loved and accepted, think about myself and my patterns.

- I like to try all kinds of things and see what works best. I take the best from whatever is on offer.

- Being able to arrive at a place of having some appreciation of my self worth.

- I tried three therapists for six sessions each. It was not successful. It had a negative rather than a positive effect. I don’t want to be opened up.

- The sessions didn’t go into depth but it did give me space. Overall I’d say it was an integrative experience.

- The most useful was to have somebody who loved me and accepted me for exactly who I am.

- I went for one session to clear the stuff that kept whamming me. It wasn’t a breakthrough.

- I didn’t feel safe enough to do work with her.

- The guy just bloody sat quietly. He may have been a student.

- It decreased the night terrors. It put things back on track but she left me with a damaging message at the end.

- As a result I decided to go on to an NLP course.

- I’d say my anxiety was 50% down and that’s a fantastic success.

- I had a series of insights. I’d talk about what happened, my reactions and my understandings and then we didn’t do anything with it.

- Spotting my own patterns.

- I ended up conforming to the therapist’s views.

- The therapist was not suitable for me.

- I saw a psychiatrist who was useless, he wanted to know who I was having sex with. It was somebody to talk to. Otherwise it had no big impact. They had a lack of warmth and compassion and that was difficult to deal with.

- A sense of a realisation that everything is your own issue. Really being able to see myself as I am.

- I went to a Freudian for my eating disorder and he told me I had ingested bad breast milk.

- The counsellor never had a clear idea of what I wanted. I could have got farther and quicker on my own.

- I came away feeling cold, unemotional and distant. I left feeling more rotten than when I came in.

- To take full responsibility for what I have created in my life.

- It made me feel better for a while after seeing her. Then I would feel bad ‘til I saw her again.

- The 4-6 weeks of counselling made my depression worse. I realised I had had depression throughout my adult life. When I said I wanted to leave counselling she didn’t argue. She just let me go.

- I went to therapy with a specific question and she offered me parts negotiation.

- I saw a counsellor and discovered my parents had been verbally abusive for a long time. I went and confronted my mom. She committed suicide.

- It was useful and interesting. At the bottom was self-acceptance.

- He said ‘you’re not trying hard enough’. I left annoyed.

- He got me in touch with my feelings and helped me cry.

- I realised I was abused. I was unjustly accused, abandoned and betrayed. It was most intense. I don’t know if I have forgiven my parents. I don’t know if it’s all healed.

- A staff counsellor made me feel worse than in the beginning. I had less self-esteem when I left.

- I saw myself as out there for other people, but really I didn’t share myself much.

- After one year I started a relationship with my therapist.

- Nice to have someone to talk to, but they kept trying to push me. It was never my choice.

- She was strong and gentle, and helped me at the same time. it was very safe and that was very important to me.

- The whole first session I told my life story. After that they kept telling me what I already knew.

- Whenever I got highly emotion she called ‘time’. All another therapist did was get me to write lists, and I already knew how to do that.

- I’d gone in with a view – with shame, and it helped me see a different way of being.

- I felt powerless and it was useful having someone outside to talk to.

Postscript

An example of an interview from the research that took place in March 2012. The annotation was added in 2023:

Evaluating Coaching

A Developing Group workshop reflected on and applied the results of the research in 2014:

Calibration and Evaluation – 3 years on