Summary

Clean Language is a way of respectfully working with other people’s perspectives of the world so that they can gain new insights into what motivates them, how they think and therefore why they do what they do. Using it as a performer-centred coaching tool enables Performers to find and enhance their motivation to train and compete and to become exquisitely aware of what they are doing in order that they can become increasingly more effective. Using Clean Language to facilitate Performers’ metaphors gives them a greater awareness of their sensory/intuitive processes and provides a language to discuss the previously ‘difficult to describe’ processes like: “How to get into the zone”.

Background

Dave Price has been coaching in sport for many years. He jointly presented a Performance Coaching course, with David Hemery [Ref 4], that I attended around 1995. That course focused my passion for discovering ‘how people change and develop’. I had learned a little about the Psychology of Motivation during my Management Education and then started a very rich exploration of the more ‘hands on’ approaches to motivation and change: notably: Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Clean Language and Symbolic Modelling (CL&SM;) and Solutions Focus.

Since 1997 I have been training/coaching managers in getting the best performance from their people, often presenting those training courses with Dave Price. During the evenings at various training venues we would often talk about Dragon Boating and what it would take for his team, the Hartlepool Powermen, to go faster. I began to get more and more interested and then found myself agreeing wholeheartedly to join Dave’s Coaching Team when he was appointed Head Coach for the GB Premier Open Dragon Boat Team in 2002. This was an opportunity to take our ideas into the context of a National Team.

Coaching approach

Our approach to coaching is not unique: it is to develop whatever the Performer brings to the training session in terms of their motivations, self esteem, beliefs, experience, fitness, strength, technique etc. It is an Inside-Out approach made popular by Timothy Gallwey’s “Inner Game” [Ref 1]. We believe the Performer is the expert in ‘what is happening for them’ and that anyone else, no matter how well they know the Performer, can only infer what is happening. A Coach who tells a Performer what they should or shouldn’t do will, at best, only be close to the Performer’s reality and will occasionally get it totally wrong. We prefer therefore to work with the information direct from the source!

This approach does not mean that we do not require certain behaviours from the team members. In fact, we believe it is essential for coaching to be effective that the performance constraints and expectations are made clear. There are things that do need to be ‘told’ when managing a team in order to align the individuals into a coherent and effective unit. For example, in the dragon boat team we gained a consensus with the team on a slower, more powerful paddling technique which therefore required the individuals to train and be selected for these capabilities.

An illustrative example of our coaching approach was when Dave Price would take a new, potential paddler into a Hartlepool Powermen training session. Dave would first take time to make them feel welcome in order to establish some level of rapport. He would tell them to wear a life jacket and then give them a paddle, without any instruction, and set them in a boat to experiment. He would question them while they were experimenting to get their focus on what was happening so that they would develop their own sense of what worked. Dave’s intention was for each paddler to have a sensory based internal model of their own technique so that they could then use that as a template to experiment and learn for themselves i.e. they would be able to: picture what was happening when things were going well; feel what a better paddling stroke was like; notice the sounds as a paddle enters the water etc.

Only when a paddler had established some sense of ownership for their technique did Dave want to offer suggestions of what else they might try or consider. This approach encourages the Paddler to retain responsibility for their performance and avoids the “learned helplessness” [Ref 2] of many individuals who are always instructed as to what to do and therefore come to believe they have little control over what they can do to make the boat go faster. We take it as a very good sign when a paddler energetically discusses what does and doesn’t work for them but is prepared to experiment further.

The added advantage of this “develop an internal model” approach is that it does not have to change as the Paddler grows in their sport. People at an expert level develop their technique so close to an optimum that it becomes difficult for the Coach to observe any useful information to feed back to the Performer. The most important information at this level is inside the expert Paddler’s mind and body. Therefore, the Paddler developing and evolving their internal model of ‘what works best’ gives them the tool to continue to improve performance even when they are the very best in the world at what they do.

The job of the Coach therefore is to:

- Facilitate the Performer to develop their awareness of what is happening, both externally and internally, so that they can refine their internal sensory model of what they want to have happen (goals).

- Facilitates the Performer’s awareness of ‘what they want from being in the sport’ (desired outcomes) in order to find the ways to maximise the motivation they need to achieve the necessary goals of training and performing.

- Ensure that the responsibility/ownership for improving performance remains with the Performer

(Note: We believe this builds on John Whitmore’s “Awareness and Responsibility” principles [Ref. 3] by emphasising the motivational ‘desired outcome’ and separating it from the enabling goals. We also maintain that individual’s goals are primarily experienced as internal, sensory experiences and that the verbal translations into specific, measurable, time-bound goals are only useful for planning and accountability.)

It is interesting to note that a performer-centred Coach does not have to have expertise in the sport to be effective in improving a Performer’s performance. In fact there are some schools of thought that believe the assumptions learned, in becoming proficient at a sport, can limit the effectiveness of a performer-centred coach because they don’t even think of asking the wonderfully creative, naïve questions a beginner can ask! We also realise that having expertise can help in getting rapport and establishing credibility with the Performers, plus it can guide what question the Coach might ask in order to raise the Performer’s awareness in a very productive area. This is a dilemma Coaches need to manage very carefully.

Internal model

The internal models we seek to facilitate in Performers consist of the sensory based representations of what it is like to do something important for performance, e.g. getting into an optimum state before a race; recovering state after something has gone wrong; being in a flow state (“the zone”). The internal model will often include the logical/analytical element expressed as beliefs, e.g. “One minute twenty is my best time!” However, peak flow states do not, in our experience, have any logical/analytical content so we try to reserve the logical/analytical to the learning processes rather than the performing processes.

These internal (goal) models are what we measure and judge ourselves against to know how well we are doing. Often, these models are subconscious although the ‘result of the measuring/judging’ is likely to be conscious. These models therefore already exist to enable us to do what we currently do and the important question is: “Are they, as they currently stand, effective in helping us achieve what we want?”

For example, a fairly common strategy for amateur Sports People is to ‘try hard’ and their model for it may be to feel all of their muscles working hard and using their internal dialogue to say things like “Ignore the pain, I must keep going!” This shows great determination but it is more likely that the optimum way of competing is to only have the muscles working that need to work; at the times they need to work. Therefore the Coach’s role would be to raise the Performer’s awareness of their sensory/intuitive experience, using the Performer’s own metaphor for “what is it like when you are performing at your best?”

The Coach needs to use different information channels to augment the Performer’s self-awareness: video feedback, times, speeds, weights, feedback from others, etc, so that the Performer can refine their internal experience of what is happening and continue to build their model of what they want to have happen. As the Performer becomes aware of their current experience/results they can experiment to develop their model of what it would be like to do it better. Once they have the model consciously in place they can track their own progress as they train.

Training once with awareness is worth 100 times training without it.

David Hemery

Another very important reason for developing a rich internal model of the ideal performance is that it provides the template for mental rehearsal. This is the practice of imagining, in the greatest sensory detail as practicable, the desired behaviours as a method to augment training and has been shown to be effective. The internal model needs to be accurate, vivid and contain the elements of control to ensure its effectiveness as a training tool. [Ref 5] However, this is not a technique we were able to use formally with the team due to the time constraints so it was left up to individuals to try this for themselves.

Typical awareness raising Clean Questions are (where [ ] are some of the Performer’s exact words):

- What kind of [ ] is that?

- Is there anything else about [ ]?

- Then what happens?

- What happens just before [ ]?

- How do you know when you are/have [ ]?

Clean Language

Clean Language is the discipline of interacting with a Performer by using their words / gestures / tonality, etc, so that the Performers do not need to interpret what is being said; because they already know what it means! A Coach using Clean Questions cannot therefore rely on understanding what is happening for the Performer, in fact, the process of understanding requires that the Performer’s information is distorted to fit the Coach’s perspective and leads to ‘unclean’ questions from the Coach.

This is a crucial point and differentiates Clean Language from say, ‘open and closed questioning’. It requires the Coach to preserve the communicated information as completely and accurately as possible; which demands a very high level of listening and observation skills. Fortunately, Clean Questions are few in number and the logic for asking them is fairly simple so the Coach is able to focus their attention completely on the Performer which encourages the development of excellent listening skills. [Ref 6]

Taking an example of a Dragon Boater talking about their paddling in the context of wanting to paddle at their best: they may say something like:

P: It’s as though I wind up like a spring and then a trigger is released and I slam the paddle in the water.

This example is a metaphorical description of their paddling experience and it might be useful to explore the ‘wind up of the spring’, ‘the trigger’ and ‘slam’ when exploring their paddling. Some Coaches hearing this would reduce the metaphor to their own logical-conceptual descriptions and would lose valuable information. Clean Questions are used whether the content is metaphorical or not and preserve the Performer’s information.

C: And when paddling at your best is there anything else about the wind up of that spring?

This question will get more description of the part of the stroke before the paddle slams into the water. And because their metaphor is isomorphic with the Performer’s experience it gives the Performer access to more information from their subconscious about it. It is not uncommon for a Performer to have an “Aha!” moment from their new insights as a result of this questioning and the Coach to be unsure as to what is going on. This is a step that some (coach-centred) Coaches are unable to take as it requires them to let go of control.

Continuing the conversation, a Performer’s insight might be:

P: If I reach too far forward I would over-wind the spring and then I would lose power.

The use of the Performer’s metaphor becomes a very precise linguistic tool to access and explore the sensory Performer’s experience for both the Performer and Coach.

The same is true for more logical statements but the tendency is for many people to believe quite wrongly that “they do know exactly what is meant” by what is being said and therefore there is a greater temptation to respond from their understanding rather than what has been communicated. In the conversation above, the Paddler may have responded to a question

C: And when you slam the paddle in the water, then what happens?

with a more factual sounding statement like

P: My Lats are pulled. (Lats = slang for latissimus dorsi, the large back muscles)

A Fitness Coach is likely to know about these muscles and the other muscles that need to be trained in conjunction with these but that would be a total distraction from the Performer’s experience, and in any case, the Performer may not know exactly what names (slang or otherwise) to give which muscles so could even be referring to a different muscle altogether. Staying with Clean Language instead of imposing an external model avoids the miscommunication and subsequent loss of rapport that can easily happen.

C: And as your Lats are pulled, whereabouts are they pulled?

This develops the Performer’s experience/internal model

Funnelling

We videotape most of our training sessions and then spend time with the team reviewing individual member’s paddling as well as the set-up of the boat. Our goal as Coaches is that every crew member has a specific action to focus on for their next training session as a result of this analysis. With a newly formed team we will take the lead with the analysis to demonstrate what we are trying to achieve. Later on we encourage team members to make observations about themselves and then, to make observations of each other. We notice that the team members soon pick up on the clean questions & begin to ask them of each other. We use this as an indication of the development stage of their cohesiveness and effectiveness as a team.

The technique we use is often called Funnelling which is to repeatedly ask a question of part of a response from someone which has the effect of getting quickly to specifics. An example:

P: I need more power.

C: And when you need more power, where could that power come from?

P: From my back muscles.

C: And what needs to happen for you to have more power from your back muscles?

P: I need to get in the gym more.

C: And you need to get in the gym more. And when you want more power from your back muscles and you need to get into the gym, then what happens?

P: I will do bench pulls, probably with 50kgs to start with.

C: And what is the relationship with bench pulls and back muscles? etc.

The coach here is raising awareness of how an exercise may, or may not, achieve the stated goal. The more conceptual words like “power” are questioned to find out what it means in very sensory-specific terms. The benefit of taking this conversation to its conclusion is that the gym training is more likely to be done with awareness and therefore to be far more effective. The conversation will regularly include the question “How will you know?” to ensure the performer is aware of the evidence for their training goals. For example:

C: As you are doing [gym exercise ‘x’], how will you know that [gym exercise ‘x’] is developing power in back muscles?

C: How will you know when you have more power in back muscles?

Modelling

The process of facilitating a Performer’s internal model is quite subtle in that it requires the Coach to create a different model from the one the Performer is developing in order to be able to facilitate the process. These two models will have similarities because they are based on the Performer’s perspective but the only information the Coach receives is what they witness as the Performer’s communication: words, tonality, pauses, gestures, etc. The Coach’s model has to consist of these ‘inputs’ only and be kept very separate from any understanding they may have of what may be happening. This is what makes the apparently simple Clean Language modelling process a challenge to learn for many people.

The Paddling Technique

One of the first tasks in getting a team together is to agree the paddling technique. The paddlers sit very close together in the boat and it is important to have sufficient synchronisation between paddlers in terms of timing and technique to avoid the injuries that can result from paddles hitting elbows, backs and heads. The research around different paddling techniques is limited, mainly informal and empirical. We had previously sought the answer from within the experience of the Hartlepool Powermen’s team so I used modelling questions with some of their best performing paddlers to identify the essential components of a good stroke that could be shared.

At Dave Price’s request I focused on ‘getting catch’ which is the skill of getting the paddle into the water in a way that generates significant forward thrust for the boat but minimises turbulence around the paddle. The problem with that turbulence is that it causes the water to flow around the paddle rather than providing a firm resistance to pull against.

I used Clean Language to map the metaphors, enabling beliefs, thinking strategies, emotions and behaviours from each of the exemplars and looked for common elements that might make up the essential ingredients. The end result was a model (external) that incorporated the essential elements of all three internal models of the paddlers who took part. (Note: This model was not formally written up but an example of part of the work is included in appendix 1 for interest).

This external model of good practice contributed to the discussions, together with the experience from the more experienced members of the team, to agree the final stroke style to be adopted by the National team. There was some flexibility in that individuals could adapt the finally agreed external model to suit their own physiologies where this improved overall team performance and did not harm any other team members. Some team members had to cope with significantly changing their paddling technique on top of the other training burdens they were taking on to be in the team. We then shared the results of this agreed external model through our normal coaching:

C: What would it be like if you believed that you can always get perfect catch from the correct position of your body prior to slamming in the blade?

This is certainly not Clean as it is inviting the Performer to ‘try on’ a belief from the external model to see how it might suit them (and if not, we try something else to find what does suit in order to get the desired result). We could say to another paddler who is rehearsing the stroke and who does not yet have their own metaphor:

C: Imagine your body has a spring and that as you fully rotate now, prior to slamming in the blade, you are at the fully wound position. And when that spring is fully wound, is there anything else about that spring?

This again is not Clean as we are inviting the Performer to ‘try on’ someone else’s metaphor but if it is done using generalised statements, then it can give the opportunity for the Performer to adapt that metaphor to become their own (autogenic) metaphor with its own unique attributes.

It is preferable to use the Performer’s own metaphor for the stroke and explore the isomorphic elements between their internal model and the external model. However, the reality of an amateur sport with a team of about 30 people spread right across the country and meeting on average every other weekend meant it was not possible to develop metaphors for many of the team members. So sharing a model using the metaphor and some logical/analytical elements (e.g. “Notice what happens to the angle of the paddle in the water when your inboard hand is closer to your head.”) was the practical way forward.

Metaphor and 'the zone'

What we had not anticipated was that we would start using Clean Language for the development of autogenic metaphors for different activities with a variety of different durations. For example: the start of the race, the whole race, training in the gym, finding the motivation to go training or how to get into the flow state. This was mainly done informally and again, it gave us the language to talk to individuals about the different aspects of training and competing that was not available to us before. We believe that a significant benefit of this is that the Performers develop models within models which start to ‘bring everything together’ on both an intuitive and logical level.

The more the Performers have effective and holistic internal models the easier it is for them to ‘repair the damage’ that can be done by analysing everything down to its component parts. Just remembering what it was like to learn to drive a car with all the many rules to remember compared with the experience of having driven for many years will show that for high performance, the non-rule based actions are more common. Reductionism has its place in learning to improve performance but, we believe, a holistic perspective is better for high performance.

We have done some work with the high performing flow state that is sometimes referred to by athletes as “being in the zone” (including a morning at the Sports Science Unit of Teesside University). What excited us about modelling the zone was that it is commonly described by athletes as being a non-verbal state, and therefore modelling the Performer’s metaphorical experience was congruent with the state itself. To put it another way, when a performer loses their flow state of being in the Zone, internal dialogue like “S**t, I’ve lost it!” is unlikely to help them regain it whereas having a greater sensory/intuitive awareness of the state, and how to move towards it, we believe, is far more useful.

Conclusion

The discipline of using Clean Language in performer-centred coaching improves the effectiveness of the awareness raising process and helps to build rapport through the Performer’s communication being valued. These are both critical precursors to effective performer centred coaching. Clean Language facilitates both logical/analytical and sensory/intuitive awareness and can therefore be more holistic in making unconscious thought processes available for the conscious mind.

The practise of Clean Language Modelling enhances questioning skills and the preservation of the Performer’s original communication so that essential information is not lost. This exploration of the use of Clean Language in our coaching has been guided by our intuition and logic around what Performers report as working for them and this could provide some fertile research areas for Sports Psychology.

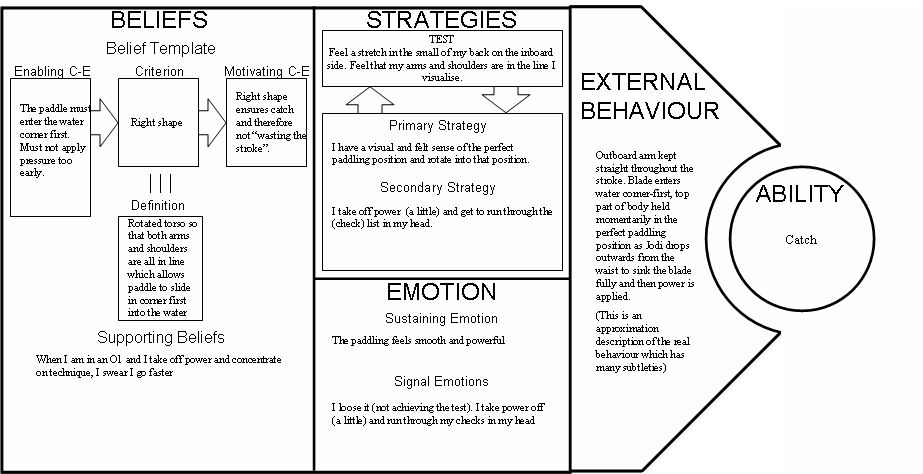

Appendix 1

Part of a model of catch from one exemplar using David Gordon and Graham Dawes’ Experiential Array [Ref 7]

(Full-size version available for download)

References

- Book: Inner Game of Tennis, W Timothy Gallwey.

- Research: Learned Helplessness, Martin E P Seligman

- Book: Coaching for Performance, John Whitmore.

- Person: David Hemery MBE, Gold Medal 1968 Olympics, 400m hurdles. The first President of UK Athletics.

- Research (illustrative example): Denis, M. (1985). Visual imagery and the use of mental practice in the development of motor skills. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Science, 10, 4S-16S.

- Book: Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling, James Lawley & Penny Tompkins

- experiential-dynamics.org

© Ned Skelton, 2005

Ned Skelton is a Director of the Clean Coaching Company Ltd. which focuses on developing managers and management teams to continually improve their business performance.