Paper presented (as Fee Robinson) to The Third International Neuro-Linguistic Programming Research Conference, Hertfordshire University, 6-7th July 2012.

A summary of the paper was published in Acuity, No. 4, 2013. Download original article (PDF).

Abstract

This study investigated the effects on well-being of using clean language to explore employees’ experiences of organisational change at its best in a UK Special Health Authority facing ambiguity and rapid change.

Following Lawley et al. (2010) a clean language research methodology was applied to explore whether there was a connection between metaphorical exploration of organisational change at its best and well-being, whether the impacts of group and 1:1 interventions differed and whether patterns could be detected to provide insight about resourcing individuals through change.

The quasi-experimental study involved control, 1:1 and workshop groups in an interrupted time-series comprising initial, post-intervention, and twelve-week post intervention well-being measures. The study included exploration of lived experiences of organisational change and of experiences of the study interventions. The study provides evidence of clean language efficacy in a business change setting and practitioner guidelines for exploring metaphor.

Introduction

This study investigated empirically whether, and phenomenologically how, the exploration of metaphor using clean language impacted well-being during a period of organisational change. The current study was prompted by anecdotal evidence of the benefits of using metaphorical approaches during a period of change in an National Heath Service (NHS) Special Health Authority.

In the study organisation, internal change to improve efficiency and effectiveness had coincided with the implementation of radical change across the NHS and a challenging fiscal situation nationally that required deep, sustained spending cuts. The organisation was operating in an increasingly fast-moving, complex, and ambiguous environment.

The organisation development (OD) team worked to support leaders in making sense of the changing environment both externally and internally because they were expressing discomfort and distress about the degree of change and how to lead others through it.

The OD team used metaphor repeatedly. This included facilitating individuals and groups to generate their own metaphors to make sense of their experience, introducing metaphors to elucidate concepts, and facilitating the sharing of metaphors between leaders and the wider organisation. Anecdotally, these interventions had a positive impact, individuals reported feeling more at ease, making sense of events more readily, and increased motivation.

The study informs the body of OD knowledge and contributes to psychotherapeutic understanding of the impact on well-being of using clean language. The study is relevant to Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) given that clean language is an approach modelled using NLP techniques, and is closely associated with the NLP community, being featured at NLP conferences and as part of some NLP trainings.

Literature Review

This section briefly defines well-being and examines the impact of organisational change on it. It goes on to explore the meaning of metaphor and its centrality in human meaning-making, before introducing clean language and reviewing the literature about its efficacy in supporting well-being.

Defining well-being

Ryan and Deci (2001) note that well-being is usually described in one of two ways, as positive affect or happiness (hedonistic definition), or as finding meaning / fulfilling potential; the degree to which the individual is fully-functioning (eudemonic definition).

The two constructs refer to different aspects of well-being, the first how one feels, the second how one functions. In the workplace, Marks (2005) defines well-being for an employee as, “their experience of their quality of life” (p. 21) and within this includes both satisfaction and personal development. This study follows Marks by considering well-being to encompass hedonistic and eudemonic dimensions of human experience.

The Impact of Ambiguity and Change on Well-being

There is literature that argues that organisational change can have a detrimental effect on well-being (Miller 2011, Cheal 2009a, Cheal 2009b, Jordan 2004, Schabracq and Cooper 1998) and that change management interventions can mitigate this deleterious impact (Fredrickson 2009, Kiefer 2002, Bridges 1987, Callan 1993, Martin et al. 2005). This section provides a brief insight into this literature.

Miller (2011) provided results from an organisational survey indicating that job insecurity and the scale of organisational change is weighing heavily on the UK’s workforce. The report indicated 40% of public sector organisations were planning redundancies and that this was connected to employee stress and anxiety, negatively impacting well-being. Miller (2011) indicated that the most common public sector causes of stress are the amount of organisational change and re-structuring.

Cheal’s (2009a) study of the nature and impacts of paradox on people in organisations used qualitative methods to explore the experience of eighteen managers from a number of organisations. Cheal defined paradox as dilemmas, tensions, double binds, conflict and vicious circles. He found that paradox has a range of effects, and that the effects of paradox were without exception negative.

Cheal (2009a) connects paradox to change, noting that as the pace and amount of work rises, the more paradox occurs in the form of conflicting priorities and dilemmas that employees need to resolve quickly. Cheal (2009b) likens the impact of paradox to learned helplessness, which Seligman (2003) contends can cause depression.

Jordan (2004) indicated that change is an inherently emotional process, producing a range of feelings in individuals including excitement, enthusiasm, creativity, anger, fear, anxiety, cynicism, resentment and withdrawal.

There are a range of interventions that support well-being through change (CIPD 2011, Schweiger and De Nisi 1991, Litchfield 2011), including those that support resilience (Liossis et al 2009), and positive psychology interventions (Lyubomirsky 2007, Sheldon and Lyubomirsky 2006).

Metaphor, Meaning-making and Well-being

A strong theme running through the literature about effectively supporting well-being during change is meaning-making (Kiefer 2002, Bridges 1987, Mobray 2011). This section explores how metaphor is relevant to this.

Metaphor is defined by Lakoff and Johnson (1981) as: “thinking of one thing in terms of another” (p. 5)

Classical theorists since Aristotle have referred to metaphor. Traditionally metaphor was seen as an expression of thought, rather than as the basis of thought itself (Lakoff 1993). Lakoff explains that the way metaphor is perceived has developed to recognise that thought is metaphorical in its nature.

Lakoff and Johnson (1999) express this idea more strongly, saying that cognitive science indicates: “the mind is inherently embodied. Thought is mostly unconscious. Abstract concepts are largely metaphorical” (p. 3). Geary (2001) builds on this theme, observing that:

“metaphorical thinking – our instinct for not just describing but for comprehending one thing in terms of another, for equating I with an other – shapes our view of the world, and is essential to how we communicate, learn, discover and invent” (p. 3)

Thibodeau and Boroditsky (2011) conducted a study of the impact of metaphors on the solutions study participants suggested for reducing crime in a fictional case study. The study involved presenting the same data with different metaphorical frames (a virus or a beast), and explored the way participants responded to them.

Thibodeau and Boroditsky (2011) demonstrated that the metaphorical frame applied influenced the nature of the solutions participants suggested. A single word referencing the metaphor was enough to prompt processing that fitted the metaphorical frame offered. They found that the metaphor was only impactful if it was presented within the context of the study and that a metaphor introduced early was more impactful than one introduced at the end of the case study. Finally, they noted that participants were not aware that their thinking was being influenced by the metaphor used.

Lawley (2011) commenting on Thibodeau and Boroditsky’s study argues that once we buy-in to a metaphor we are constrained to follow its logic, and that we may not realise that our choices are limited to what makes sense within it. This concurs with Morgan (1997) who hypothesises that metaphors create insight and have strengths, but that they also distort. He notes that: “the way of seeing created through a metaphor becomes a way of not seeing” (p. 5). The author contends that this makes working with metaphor a useful intervention to explore in managing change.

Defining Clean Language and Symbolic Modelling

David Grove, a counselling psychologist, developed a clinical approach for resolving clients’ traumatic memories in the 1980s (Grove & Panzer 1989). Grove worked with clients in a way that honoured their choice of words rather than paraphrasing, and devised ‘clean language’ questions which contained as few assumptions and metaphors as possible (Sullivan and Rees 2008).

Grove’s approach enabled his clients to explore their naturally occurring metaphors and gain an understanding of their inner world. Referred to as their ‘metaphor landscape’, Grove found that when his clients worked in this way it enabled the resolution of their issues.

Grove’s approach was modelled by Lawley and Tompkins (Tosey 2011). Lawley and Tompkins distilled, codified and extended Grove’s work (Sullivan and Rees 2008) and called the methodology they developed Symbolic Modelling. Clean language questions presume only metaphors of time, space, form, and perceiver, the raw materials of symbolic perception (Lawley and Tompkins 2000), leaving all other metaphorical content to emerge from the individual’s metaphor landscape.

Grove (1998) indicated that the facilitator’s role is to visit the client’s model of the world and unfold solutions contained within the language and logical boundaries of that world. He believed that every ‘negative’ symptom has within it a solution that can emerge to become a resource. He summarised his approach by saying: “clean language engages and interrogates symptoms until they confess their strengths” (p. 2).

Clean language is essentially a set of questions, they can be used in a variety of contexts from marketing to police investigations, anywhere that the benefit of eliciting information without introducing metaphors from outside is useful (Sullivan and Rees 2008). Given Thibodeau and Boroditsky’s (2011) findings about the ease of influence available through metaphor introduction, the author considers this approach potent for research and facilitation purposes.

The Effect of Clean Language on Well-being

Clean language practitioners claim that use of clean language has an impact on well-being (Lawley and Tompkins 2000, Tompkins and Lawley 2004, Doyle 2010, Sullivan and Rees 2008).

Lawley et al.’s (2010) study employed clean language to explore six participants’ experiences of work-life balance. Participants undertook a one-hour session exploring their experiences of work-life balance at its best and not at its best. A follow-up session further explored their metaphor landscape, and their experience of the intervention.

While the study did not aim to make any changes in participant’s well-being, there were effects for participants. The authors found that some interviewees were deriving real benefit from the experience of exploring, describing and drawing their metaphor landscapes. Furthermore, the technique led to a growing awareness of work-life balance and some participants decided to make changes following the intervention. Lawley et al (2010) present qualitative data that makes clear that participants perceived that they derived benefits from their experience.

The literature about the effectiveness of using metaphor (Jacobs and Heracleous 2004, Abel and Sementelli 2005), clean language and symbolic modelling (Lawley and Tompkins 2000, Tompkins and Lawley 2004, Sullivan and Rees 2008, Lawley et al. 2010, Doyle 2010, Walker 2006), tends to be qualitative, anecdotal, and not specific to an organisation change context. The current exception to this is Doyle et al. (2010). The current research addresses this gap in the literature.

Methodology

This study deployed a combined quantitative and qualitative methodology. The quasi-experimental aspect of the study provided an interrupted time series with a non-equivalent control group to establish whether a significant relationship could be found between clean language interventions and levels of well-being. Phenomenological methodology was used to examine lived experience of organisational change by exploring participant metaphors and participant experiences of the interventions and their impact on well-being. Phenomenology is the study of how we experience the world, suggesting that reality is unknown because all humans have is subjective perception (Schulz 2004).

The study objectives were to establish whether there was a connection between metaphorical exploration of organisational change at its best and well-being, whether the impacts of group and 1:1 interventions differed and finally whether any patterns could be detected to provide insight about resourcing individuals through change.

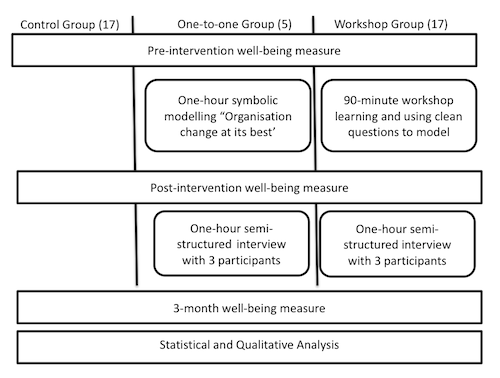

Figure 1 provides an overview of the methodology. Three well-being measures were taken, before, after and twelve weeks after the interventions. Two intervention groups were engaged, one attended a ninety-minute clean language workshop, the other a sixty-minute symbolic modelling session. There was also a control group. Post-intervention three participants from each intervention group were interviewed about their experience to gather phenomenological data.

Figure 1: Methodology Overview

For this study, a well-being measure was sought that focused on positive functioning rather than a lack of well-being, encompassed both hedonistic and eudemonic aspects of well-being and was simple, face-valid for participants, and reasonably quick to complete.

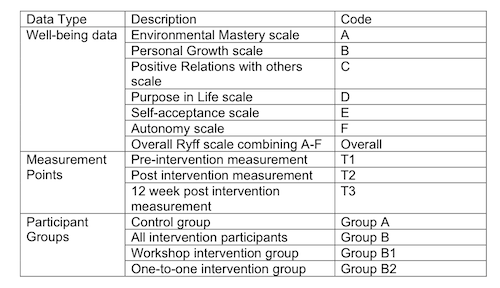

The measure selected was the Ryff Well-being scales. Figure 2 provides a summary of the six constructs measured (Ryff 1989).

|

Self Acceptance: holding positive attitudes towards oneself and one’s past life. Positive Relations with Others: warm, trusting interpersonal relationships, the ability to love and feel empathy. Autonomy: self-determination, independence and regulation of behaviour from within, an internal locus of evaluation. Environmental Mastery: ability to advance in the world, to choose and create environments, active participation in and mastery of the environment. Purpose in Life: purpose and meaning in life, goals, a sense of directedness and intentionality. Personal Growth: continuing to grow, to develop one’s potential and expand as a person. |

Figure 2: Ryff Sub-scales constructs (Ryff 1989)

The Ryff scales used were the fifty-four item scale, with each of the six sub-scales made up of nine items. Participants answered each item using a six point Likert scale that has an ordinal scale for analysis. This results in a global measure of well-being based on the mean of the participants’ responses, as well as a mean score for each sub-scale.

One-to-one intervention

For the one-to-one group, the intervention was a one-hour symbolic modelling session. The study echoed Lawley et al (2010) by using clean language questions to explore experiences of organisational change at its best, but did not echo the previous study by contrasting this with exploring experiences of it not at its best. The hypothesis was that this positive focus might support well-being.

In this study, following the one-hour interview, the participants were asked immediately to draw a representation of their metaphor. This is standard practice in symbolic modelling (Lawley et al. 2010).

Workshop Intervention

Groups of five or six participants were introduced to the basic clean language questions. The ninety-minute workshop comprised a short demonstration, and participants working in pairs supported by the author as needed. At the end of the workshop, participants were asked to draw a representation of their metaphor.

The workshop was designed using the 4MAT system of training (McCarthy 1990). First the context was explained and the benefits of learning about clean language were articulated. Next, learners were introduced to the clean language methodology. There was then a demonstration, before participants experimented, supported as needed. Finally the group explored how they might apply their learning outside the workshop. McCarthy (1990) notes that this cycle is a change cycle as much as a learning cycle, making it particularly relevant for this study. As with the one-to-one group, participants captured their metaphor visually at the end of the workshop.

The intended outcome of the workshop intervention differed from the one-to-one intervention. The one-to-one enabled exploration at depth. Having less depth, the workshop was designed to build skills participants could apply day to day to enable them to explore their own and others’ experiences. Rather than solely being modelled, this group was being given a succinct introduction to modelling.

Data Analysis Techniques

Quantitative analysis

A deductive approach was taken to the quantitative element of this study, analysing the data to establish whether the data support the hypothesis that exploring metaphorical representations of experiences of organisational change would increase well-being or whether a null hypothesis of no effect was demonstrated.

To analyse the data, a well-being score was created for each of the six well-being sub-scales (A-F) and the overall total. Data was analysed in an IBM SPSS statistical analysis programme. In the results data is coded as described in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Data Codes for quantitative analysis

As the score created was a scale measure there was a possibility of using parametric tests. Data was analysed before each test to determine whether parametric assumptions were met. Because the sample is small, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for a normal distribution, and the Levenes test was used to check if the variance was equal (Field 2009). Given the small sample size could potentially cause bias in the results, for completeness and to check consistency both non-parametric and parametric tests were always undertaken.

The results indicate the outcome of the Shapiro-Wilks and Levenes tests on a case-by-case basis by indicating which result can be relied on. Throughout analysis, significance was tested at the 95% significance level (p < 0.05) in line with standard statistical procedures (Field 2009).

To establish if the interventions affected well-being overall, an across-group analysis of the effects of the different interventions was performed. A separate variable was created for each of the six scales and for overall well-being based on the difference in means between the measurement points. Analysis was then conducted using an independent T-test (parametric) and Mann-Whitley test (non-parametric) to compare the intervention and control groups.

To compare the effects of one-to-one and group interventions, the first test completed for the control group and two intervention groups separately was for the movement of means over time. For comparing two points in the time series (T1-2 and T1-3) the parametric test used was the dependent t-test and the non-parametric the Wilcoxon Signed (Field 2009).

Qualitative analysis

An inductive approach was taken to analysing the transcriptions of the semi-structured interviews, exploring participant experiences of the interventions to ascertain whether patterns and themes could be ascertained. In line with Cheal (2009a) individual comments were isolated, and then a process of sorting them into themes was undertaken by grouping together similar comments, and using commonly used words as labels for them.

Limitations

Study population

The study organisation was subject to a significant amount of change during the research, and unsurprisingly was taking steps to manage this change. This does mean that events outside the study could confound the well-being results. This limitation was mitigated as far as possible by randomising the three study groups. The small size of the one-to-one group made quantitative analysis challenging. A larger study group would have been preferable.Study design

The workshop intervention used in this study involved teaching clean language questions, rather than using clean language to develop a group metaphor. The latter approach would have been more comparable with the one-to-one intervention. With hindsight, the contrast in interventions in the view of the author risked over-complicating the study. Study robustness could have been enhanced by having the data analysis checked by an independent research statistician. In addition, the transcripts/recordings could have been vetted for the author’s adherence to the principles and practices of symbolic modelling and clean language. Lastly, the quotations extracted from the transcripts could have been reviewed for reasonableness of choice. Lack of budget prohibited bringing such resource during the study.Researcher expertise in using clean language

In their 2010 study, Lawley et al. note that the competence of the interviewer in using clean language is important to ensure that the interview remains true to the methodology. The author in this study had spent eleven days studying clean language with James Lawley and Penny Tompkins. While competent in its use, the author did not consider herself to be an expert; this may have impacted the quality of the findings. This limitation was mitigated by seeking advice from Rupert Meese, a member of the Lawley et al. (2010) team.Researcher’s dual role

During the study period, the author was an employee of the study organisation, working in the organisation change arena. Some participants knew the author and this relationship might have impacted their responses in questionnaires and during interventions. These limitations have been mitigated by the author’s reputation as a coach within the organisation, and her demonstrating confidentiality and ethical consideration in relationships generally. In addition, written information explaining the study method and confidentiality measures and the use of clean language as a research methodology have a mitigating effect, because clean language avoids introducing researcher content into the dialogue. Given there were three groups, a one-way ANOVA (parametric) and Krustal-Wallis (non-parametric) was carried out to provide an indication of whether the change in means over time differed by intervention type.Results

Quantitative results summary

In summary, the quantitative analysis demonstrates a number of significant well-being correlations.

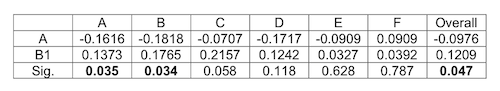

12 weeks after the intervention, there was a statistically significant difference in the way overall well-being had changed for the intervention groups compared to the control group (p=0.047).

12 weeks post-intervention, Personal Growth (p=0.034) and Environmental Mastery (p=0.035) subscales demonstrated a significance well-being difference for the intervention group compared with the control group.

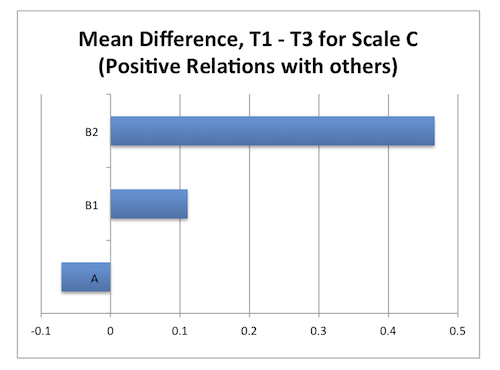

12 weeks post-intervention, the Positive Relations with Others sub-scale showed a statistically significant difference across the three groups, one-to-one, workshop and control.

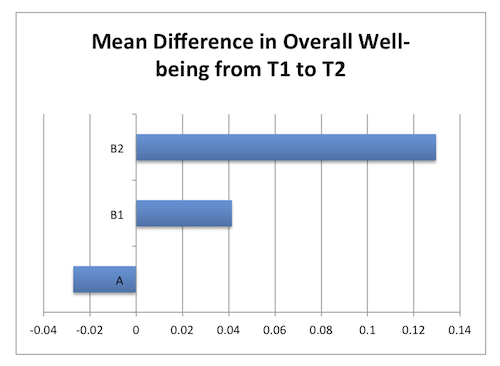

Post intervention, the Autonomy sub-scale (p=0.020) showed significance in the change in well-being for the one-to-one group.

At twelve weeks, the Positive Relations with Others sub-scale was close to significance (p=0.058) when comparing the control and interventions groups. This was also true post-intervention for overall well-being for the one-to-one group (p=0.080).

It should be borne in mind that this study is quasi-experimental, and causation is not demonstrated by these results, they indicate correlations only.

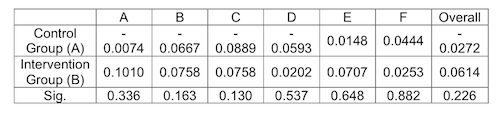

Comparison of control and intervention groups

Post-intervention control group overall well-being fell, and for the intervention group it rose, demonstrated in figures 4 and 5. Only respondents completing both measurement points are included in the data. This difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 4: Mean Difference and independent t-test results for Group A and Group B T1 to T2

Figure 5: Mean Difference, Group A and Group B for T1-T2

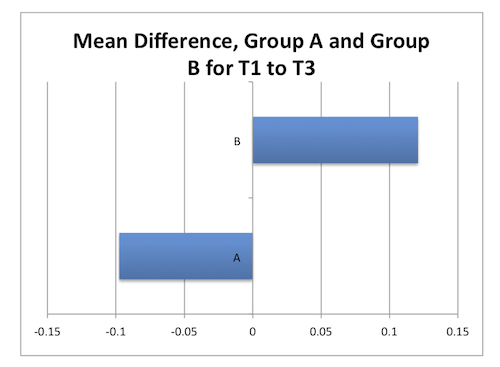

Twelve weeks post-intervention, analysis was conducted including those respondents who had provided data at all three measurement points only. By this point, there was a difference in the way well-being had moved between groups; the control group’s overall well-being again fell, and the intervention group’s rose. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate this difference, which is more marked than at T2, and is statistically significant (p=0.047).

Figure 6: Mean Difference, Group A and Group B for T1 to T3

Figure 7: Mean Difference and independent t-test results Group A and Group B for T1 to T3

Breaking down the statistics to each well-being scale, there was a significant difference between control and intervention groups for Personal Growth (0.034) and Environmental Mastery (0.035). Positive Relations with Others narrowly missed significance (0.058). This data shows that for the first study objective, establishing whether the interventions impact well-being, the data indicate that there is a correlation between interventions and changes in well-being.

Group A, B1 and B2 results

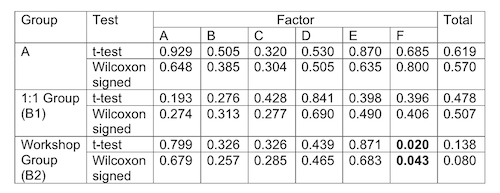

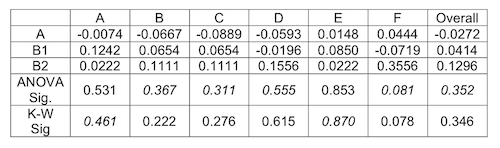

Post-intervention, when analysing the intervention groups separately the only significant correlation is for Autonomy (0.020) for the workshop group. For the workshop group the overall well-being correlation significance was 0.080, narrowly missing significance.

Figure 8: Significance (p) values indicating difference (or not) for Groups A, B1 and B2 between T1 and T2.

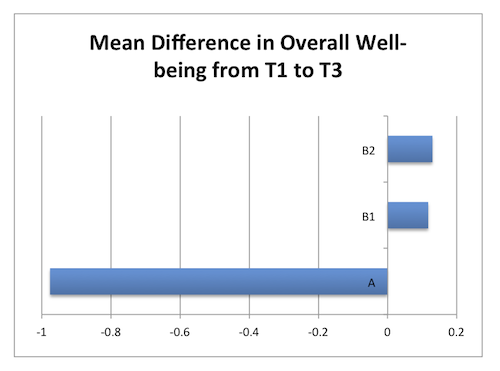

Figure 9 shows that mean overall well-being for the control group fell post-intervention (-0.272). The mean for the workshop group increased (0.0414), the mean for the one-to-one group also increased (0.1296). While the changes are not significant it is apparent that well-being has increased, and increased more for the group undergoing the more intensive intervention.

>Figure 9: Mean Difference in overall well-being from T1 to T2<

Figure 10: Mean Difference and one-way ANOVA / Krustal-Wallis significance results for Groups A, B1 and B2 for T1 – T2. Italics in the table indicate the relevant result.

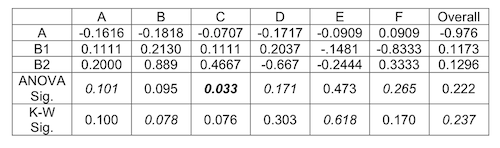

The mean well-being score for the control group fell by twelve-weeks to a larger degree than it had post-intervention (-0.976). The mean for the workshop group increased (0.1173), the mean for the one-to-one group increased slightly more (0.1296). While the changes are not significant it is apparent that well-being has declined for the control group, and increased for intervention groups, with minimal difference between one-to-one and group interventions. Figures 11 and 12 show these results.

Figure 11: Mean Difference in Overall well-being from T1 to T3

Figure 12: Mean Difference and one-way ANOVA / Krustal Wallis significance results for Groups A, B1, B2 for T1 to T3

At twelve-weeks, the change in well-being is significant for the Positive Relations with Others sub-scale looking across the groups. This indicates differential correlations across the different interventions. Figure 13 illustrates this data.

Figure 13: Mean Difference T1-3 for Scale C (Positive Relations with Others)

In considering the second study objective, establishing whether one-to-one and group interventions have a differential effect, the data in this section indicates that while the overall well-being effects are not significantly different, there is a significant difference at the sub-scale level.

Qualitative Results

Six individuals were interviewed about their experience of the study interventions, three from the one-to-one intervention and three from the group intervention.

In the interviews, participant drawings were used as a starting point to revisit metaphor landscapes of ‘organisation change at its best’, and clean language questions were used to elicit information about participant experiences of the interventions.

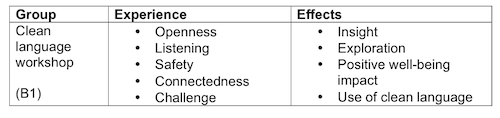

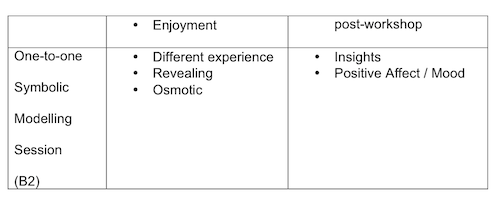

Participant comments were analysed for patterns, this section summarises the themes (Figure 14). In the six semi-structured interviews, all participant metaphors had changed substantially. A case study is presented for one workshop participant to illustrate their experience and its effects.

Figure 14: Summary of Themes from interviews

Case study

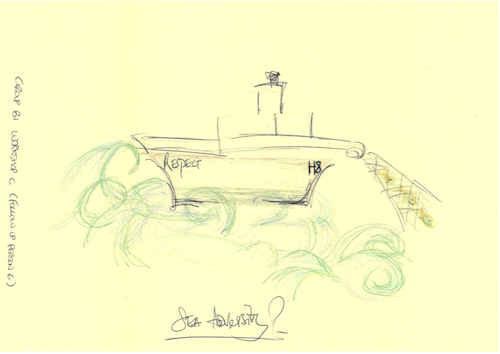

The participant’s metaphor for organisational change at its best in the workshop was a trawler with a net of people being dragged along behind the trawler, many of whom didn’t want to come.

Figure 15: Group B1 Workshop C Participant Drawing

In contrast, during the follow-up interview the participant talked about “allowing people to come along at their own pace” and being “just as comfortable with those people remaining where they are.”

The metaphor had developed into a “collective” of people who “have all got different skills” on a walk together in a landscape of “flat plains and high mountains” that “provides you with your own milestones and goals to just keep going.”

Figure 16: Group B1 Workshop C Same Participant Follow-Up Interview Drawing

The metaphor change was transformative for this participant’s energy; she was much slower and calmer in delivery as she described celebration, warmth and sustenance as part of her new metaphorical landscape.

The participant described the brief clean session by saying: “it un-clutters my messy mind and stops my racing thoughts.”

She also reported that she was picturing not thinking, this had an impact for her: “my baggage comes in thoughts rather than pictures so my baggage instantly went, ”and as a result she felt: “energised, happy, still but not dead.”

She reported that: “it’s not an arrival, it’s just I’ve landed somewhere and there is something else out there.”

She was emotional in the interview, noting that: “much as I am having an emotional reaction, it is a cathartic reaction.”

When asked if there was a relationship between the intervention and their well-being she said: “absolutely, categorically yes.”

In the view of the author, the individual had experienced a noticeable shift in the way she made meaning of past change experiences between the workshop and the follow up interview. This is an sizeable impact from a twenty-minute exploration facilitated by a colleague who had just learned the clean language questions.

Discussion

Well-being impacts

Various studies have indicated that organisational change negatively impacts well-being (Miller 2011, Cheal 2009a, Jordon 2004). This study supports these suggestions. The control group’s well-being fell both post-intervention and at twelve-weeks post-intervention.

The negative impact of organisational change was apparent in two of the interviews, with participants exploring the personal impact of on-going organisational changes. One re-framed their experience through the intervention, for the other it remained a source of dissatisfaction.

The control to intervention group comparison demonstrated that while there was not a significant change in well-being shortly after the intervention, twelve weeks later there had been. Addressing the first question of this study, this indicates a positive correlation between metaphorical exploration using clean language and well-being. The difference was significant when the difference in groups was analysed, and not significant looking at groups in isolation. This is because of the control group’s well-being falling in contrast to the intervention group’s rising.

The positive well-being finding supports the case study reports in Tompkins and Lawley (2004), Lawley et al. (2010), Doyle (2010), Sullivan and Rees (2008), and Walker (2006) which suggest positive effects of different kinds for intervention participants.

All six of the participants interviewed post-intervention had metaphors at this stage that were different to those they explored in the original intervention they took part in. It is interesting to note that well-being overall for the intervention groups increased at the same time as their metaphors were evolving. The connection between well-being levels and evolving metaphors is worthy of further research in the opinion of the author.

The evolution of metaphors over time fits with the pattern of well-being rising over a period of time rather than immediately. This reflects the finding in Tompkins and Lawley’s (2004) case study where a participant was experiencing positive effects from symbolic modelling some six months post-intervention.

Comparing the intervention and control groups after twelve weeks, Environmental Mastery and Personal Growth were significant correlations, indicating that participants were more positive about growing and expanding as a person, and their ability to advance in the world and choose and create environments. This supports Callan’s (1993) contention that the effects of organisational change are mitigated by empowering employees and encouraging them to take action.

The only significant result shortly post-intervention was for the one-to-one group, for Autonomy. This scale measures self-determination and an internal locus of evaluation. Given the focus of clean language described by Grove (1998) and Doyle (2010), holding that self-generated solutions and client wisdom are primary, this result is perhaps unsurprising. Group interventions were conducted by participants, not experienced clean facilitators, which may account for the lack of effect in this sub-scale when the workshop group participants are included.

A predominant theme in the literature was the need for assistance in meaning-making during organisational change (Kiefer 2002, Bridges 1987, Mobray 2011). Both the workshops and one-to-ones provoked thought and enabled insight, this was a strong qualitative theme.

Lakoff (1993), Lakoff and Johnson (1999) and Geary (2001) point to the power of metaphor to enable meaning making. Lawley and Tompkins (2000) indicate that symbolic modelling enables an individual to build a coherent metaphor landscape, this reflected the experience of a one-to-one participant who found that they “built up a story, a whole picture.”

This study confirms the potential for clean language interventions to support well-being in the context of organisational change; the author contends that its efficacy in supporting meaning-making is a prime reason for this.

One-to-one and group interventions

The second research question asked whether there was a difference between the effects of an one-to-one or group clean language intervention.

Post-intervention, the one-to-one intervention had a stronger correlation with well-being than the group intervention, but not to the level of significance. Twelve weeks later the effect of both interventions was positive and of similar magnitude, again not reaching significance.

Qualitative data reflected a positive impact on well-being for five interviewees, with the last one reporting no impact but presenting in a way that indicated frustration. Considering the quantitative and qualitative evidence this author contends that the magnitude of effects of the one-to-one and group interventions were broadly similar.

However, differential experiences were noted. Comparing the control and two intervention groups after twelve weeks, Positive Relations with others showed a difference between interventions, with the largest positive correlation in th one-to-one group. Stiles et al (2006) note the power of the therapeutic alliance in individual therapy; this may have been a factor in enabling the change in the scale measuring ability to form warm, trusting relationships. Workshop participants stressed creating a climate of listening was important in enabling openness and safety, accounting for the positive correlation seen in the data. However, they did not have the opportunity to connect for the period or at the depth experienced in one-to-ones.

The one-to-one intervention had a significant correlation with autonomy post-intervention, encouraging independent thought; the data do not show the workshop having this effect. In contrast, qualitative data revealed that the workshop intervention led to more conscious application of learning with participants using clean language while the one-to-one intervention provoked insights but led to only one interviewed participant consciously experimenting.

The nature of the intervention differed, no new skill was being taught in the one-to-one intervention that participants could readily go and apply, their shifts were more in meaning than at the level of skills. This difference is significant in guiding OD practitioners, if personal insight and meaning-making is desired then the symbolic modelling intervention provides this, if behavioural change is the goal, this study found that the clean language workshop was more efficacious. Further research could combine the two approaches to see if there was an additive effect or not.

Intervention guidelines

The final research aim was to identify any patterns in participant experience that provide intervention guidelines for those supporting others through organisational change.

Three significant themes emerged. Firstly, metaphors and meaning changed between the intervention and the follow-up interviews. This fits with the quantitative findings of the study indicating that well-being effects take time to emerge, and also with the usual pattern of symbolic modelling interventions, which usually happen as a series (Lawley and Tompkins 2000). The qualitative results suggest that interventions that recur are likely to be more helpful in supporting well-being. In addition, metaphors evolving happened concurrently to well-being being sustained relative to a control group, indicating that metaphorical work is a useful intervention.

The second theme that emerged was that themes occurred in the metaphors produced in workshop groups, indicating that individuals influence each other’s metaphors. The study also found that the themes across participant metaphors resonated with the metaphors used in the organisation before the study. The author has no way of knowing whether the similarity in metaphors is coincidental or causative, however given the findings of Thibodeau and Boroditsky’s (2011) in their crime study; recognising that the metaphors one uses have a marked effect on the way people process has implications for OD practitioners and therapists.

Lastly, in terms of the nature of the interventions, safety that enabled openness and came from listening were strong themes from the workshop group, with the one-to-one intervention providing guidance and enabling information to be revealed. These themes reflect Tompkins and Lawley (2004) in which the participant noted the process provided safety and support. In any intervention that may be a different experience for participants, which was the case in this study, this climate of safety, and openness will be important. The nature of clean language makes it ideal to create these conditions.

Conclusions

This study has found that exploring metaphorical representations of organisational change at its best correlated significantly with increasing well-being during a period of organisational change; potentially mitigating the deleterious effects of change and causing a small well-being uplift.

It is clear that the well-being change took time to emerge, indicating that change management needs to take place over a period of time, supporting employee meaning-making.

Group and one-to-one interventions showed similar well-being correlations over a three-month period, indicating that either may provide some benefit during change. However, the nature of the effect was different, with insights and positive affect the prime outcome for the one-to-one intervention, and workshops additionally leading to experimentation with new skills.

There are four implications of this study for clean language / therapeutic practitioners. Firstly, clean language and symbolic modelling interventions are suitable as part of the change management mix to support employee well-being. Secondly, metaphorical interventions have effects over time, undertaking interventions over a period is recommended. Thirdly, creating an open, safe environment for exploration and insight is key to supporting well-being. Finally, teaching clean language will enable application of learning into other contexts. Using one-to-one interventions may require more sessions to lead to behavioural change.

Future Research

This study has indicated that clean language interventions may have a positive effect on well-being during organisational change. Future research areas to expand understanding could usefully include a study with varying numbers of interventions to establish the optimum duration and depth of intervention. In addition, using a different workshop format to facilitate exploration of the group together rather than teaching clean language skills directly to participants. Finally, a study with more diverse participants to test whether results can be generalised.

References

Abel, C F and Sementelli, A J (2005) Evolutionary critical theory, metaphor and organizational change in Journal of Management Development 24:5, 443-458.

Bridges, W (1987) Getting them through the Wilderness – A Leader’s Guide to Transition. Larkspur California (William Bridges and Associates)

Callan, V (1993) Individual and organizational strategies for coping with organizational change in Work and Stress 7:1, 63-75.

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2011) Developing Organisation Culture: Six Case Studies. Available online (http://www.cipd.co.uk/binaries/Transforming%20culture%20(PROOF).pdf) Accessed January 2012.

Cheal, J (2009a) Exploring the role of NLP in the management of organisational paradox in Current Research in NLP Vol. 1 – Proceedings of the 2008 Conference p33-48

Cheal, J (2009b) Dilemmas and Tensions and Binds: Oh My! Managing Paradox in Organisations sourced from http://www.gwiztraining.com/ArticlesNLP.htm in August 2011

Doyle, N (2010). Creating the Conditions for Agency, presented at British Psychological Society’s Division of Occupational Psychology Annual Conference. Available at: trainingattention.co.uk/category/article-archive. Accessed August 2011

Doyle, Nancy, Tosey, Paul & Walker, Caitlin (2010). Systemic Modelling: Installing Coaching as a Catalyst for Organisational Learning, The Association for Management Education and Development – e-Organisations & People, Winter 2010, Vol. 17. No. 4. Downloaded from: http://api.ning.com/files/-pCJ-ZbcKSD-yL5RJxhyBLw41ziCbplcfSK6KGV*gsXGFiM1FHxwXZPjASdiZoaysxSuepuCWY0b-AW8jxboJ6AZuPP1SN7U/Coverandcontentsonly174P.pdf

Field, A (2009) Discovering Statistics using SPSS. Third Edition London (Sage)

Fredrickson, B (2009) Positivity. Groundbreaking research to release your inner optimist and thrive. Oxford (Oneworld publications).

Geary, J (2011) I is an other, New York (Harper Collins)

Grove, D (1998) The Philosophy and Principles of Clean Language. Available online https://www.cleanlanguage.co.uk/articles/articles/38/ Accessed October 2011.

Grove, D J and Panzer, B I (1989) Resolving Traumatic Memories: Metaphors and Symbols in Psychotherapy New York (Irvington)

Jacobs, C and Heracleous, L (2004) Constructing Shared Understanding – The Role of Embodies Metaphors in Organisation Development, Switzerland (Imagination Lab Foundation)

Jordan, P (2004) Dealing with organizational change: can emotional intelligence enhance organizational learning? In International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 8:1, 456-471

Kiefer, T (2002) Understanding the Emotional Experience of Organizational Change: Evidence from a Merger in Advances in Developing Human Resources 4:1, 39-61.

Lakoff, G and Johnson, M (1981) Metaphors we Live By Chicago (University of Chicago Press)

Lakoff, G and Johnson, M (1999) Philosophy in the Flesh, New York (Basic Books)

Lakoff, G (1993) The contemporary theory of metaphor in Ortony, Metaphor and Thought Second Edition. Cambridge (Cambridge University Press)

Lawley, J (2011) Balancing Brain Hemispheres. Available online (https://www.cleanlanguage.co.uk/articles/blogs/42/Balancing-brain-hemispheres.html). Accessed February 2012.

Lawley, J and Tompkins, P (2000) Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling, London (Developing Company Press)

Lawley, J, Meyer, M, Meese, R, Sullivan, W and Tosey, P (2010) More than a Balancing Act? ‘Clean Language’ as an innovative method for exploring work-life balance, England, (Clean Change Company and University of Surrey). Download from: Clean_Language_WLB_final_report_October_2010.pdf

Liossis, P L, Shochet, I M, Millear, P M, and Biggs H (2009) The Promoting Adult Resilience (PAR) Program: The Effectiveness of the Second, Shorter Pilot of a Workplace Prevention Program in Behaviour Change (2009) 26:2, 97-112.

Litchfield, P (2011) Mitigating the impact of an economic downturn on mental well-being at BT Group Plc in Well-being, Good Work and Society – Time for Change. The Business Well-Being Network Annual Report 2011/2012. (Purchased from Robertson Cooper)

Lyubomirsky (2007) The How of Happiness, Great Britain (Sphere)

Marks, N (2005) Good Jobs: well-being at work in Reflections on employee well-being and the psychological contract. London (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.) Document available online (http://www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/research/employee-well-being-psychological-contract-reflections.aspx). Downloaded January 2012.

Martin, A, Jones, E, S and Callan, V, J (2005) The Role of psychological climate in facilitating employee adjustment during organizational change in European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 14, 3, 263-289

McCarthy, B (1990) Using the 4MAT system to bring Learning to Schools in Educational Leadership 48, 2, 31-7.

Miller, J (2011) Under pressure – the stressed workforce in Impact Issue 37, November 2011. London (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development).

Morgan, G (1997). Images of Organisation. Sage Publications Inc (USA).

Mowbray, D (2011) Nurture Resilience – Leading HR thinkers offer their game-changers in People Management Magazine. Available online (http://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/pm/articles/2011/09/leading-hr-thinkers-offer-their-game-changers.htm). Accessed October 2011.

Ryan, R M and Deci E L (2001) On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudiamonic Well-being in the Annual Review of Psychology 2001.52.141-166

Ryff, C D (1989) Happiness is Everything, or is it? Explorations of the Meaning of Psychological Well-being in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 57:6, 1069-1081.

Schabracq, M. J., & Cooper, C. L. (1998). Toward a phenomenological framework for the study of work and organisational stress in Human Relations, 51, 625-648.

Schweiger, D M and Denisi, A S (1991) Communication with employees following a merger: A longitudinal field experiment in Academy of Management Journal, 54, 10, 110-135

Schulz, F (2004) Relational Gestalt Therapy: Theoretical foundations and dialogical elements. Accessed online at http://www.gestalttherapy.org/_publications/RelationalGestaltTherapy.pdf in August 2012

Seligman, M (2003) Authentic Happiness, Great Britain (Nicholas Brealey Publishing)

Sheldon, K M and Lyubomirsky, S (2006) How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves in The Journal of Positive Psychology 1:2, 73-82.

Sullivan, W and Rees, J (2008) Clean Language: Revealing Metaphors and Opening Minds, Wales (Crown House Publishing Ltd)

Stiles, W B, Barkham, M, Twigg, E, Mellor-Clark, J, and Cooper, M (2006) Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural, person centred and psychodynamic therapies as practiced in UK National Health Service Settings in Psychological Medicine 2006, 36, 555-566

Thibodeau, P H and Boroditsky, L (2011) Metaphors we think with: the role of metaphor in reasoning in PLoS ONE 6(2), e16782. Full text available at: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0016782

Tompkins, P and Lawley, J (2004) The Jewel of Choice, NLP News, 9. [Link available soon] Accessed August 2012

Tosey, P C (2011) ‘Symbolic Modelling’ as an innovative phenomenological method in HRD research: the work-life balance project, presented at the 12th International Conference on HRD Research and Practice across Europe, University of Gloucestershire, 25th – 27th May 2011. Full text is available at: http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/7135/

Walker, C (2006) Breathing in blue by Clapton duck pond, Counselling Children and Young People, Dec 2006, 2-5. Download from: bacp.co.uk/admin/structure/files/pdf/3214_ccyp_winter06a.pdf