Presented to The Developing Group, 16 Sept 2017

Michel Montaigne

The circumstances of the world are so variable that an irrevocable purpose or opinion

William H. Seward

The man who never alters his opinion is like standing water,

and breeds reptiles of the mind.

William Blake

Background

When did you last change your opinion?

In an age of organisational silos, confirmation bias, cognitive dissonance, belief rationalisation, heuristic processing, the illusion of validity, motivated reasoning and so on, it’s a miracle we ever change our views. And is technology creating an echo chamber effect, making it harder to hear opposing views? We contributed to a fascinating UCL project researching ways to counter algorithms which pander to our preferences and opinions by adding serendipity back into internet search.

David Ropeik suggests that changing somebody’s mind, or your own, is hard to do because common sense methods have little effect:

Why do people so tenaciously stick to the views they’ve already formed? Shouldn’t a cognitive mind be open to evidence… to the facts… to reason? Well, that’s hopeful but naïve, and ignores a vast amount of social science evidence that has shown that facts, by themselves, are meaningless.

Yet we all do change our opinions; so how does that happen?

Maintaining our opinions and preserving coherence over time is fundamental to our well-being and our relationships. We often distrust people who change their minds too easily. And yet we regularly adjust our views. How is it that some of our opinions remain constant while others can change almost without us noticing, and sometimes the change is such a shock that we are left temporarily disorientated?

For once we are thinking less about deep psychological change which happens in therapy or personal development, and more about the everyday change of opinion – a view or judgement formed about something.

This topic became of interest recently when we each caught ourselves in the act of changing an opinion.

James was listening to a political discussion when journalist Polly Toynbee said (something like) “If you didn’t think the first referendum on Brexit was a good idea, you shouldn’t call for a second referendum.” In that moment James saw the incongruence in his opinion and changed his mind to thinking a free vote in Parliament would be a better way to decide the matter. Not only that, he realised he had just changed his opinion.

This summer Penny visited Jane, a cousin she had not seen in 25 years and never particularly liked. During the visit Penny discovered the myriad of ways Jane handled incredibly difficult family situations and maintained loving and healthy relationships. Penny’s life-long opinion of Jane transformed in a day, and they now have a connection and relationship that was not possible before.

Definitions and distinctions

The dictionary definition of an opinion is “a view or judgement formed about something, not necessarily based on fact or knowledge”. It is our opinion that this definition misses a number of points:

- Opinions are always held by someone, and therefore are personal.

- Opinions are always contextual. Even a small change in the context can result in people having a different opinion. (Undervaluing context is so common that in social psychology it is known as the fundamental attribution error.)

- The tag “not necessarily based on fact or knowledge” implies there are facts or knowledge that exist independently of someone’s opinion.

Our Thesaurus lists 40 comparable words for ‘opinion’:

belief, judgement, thought(s), school of thought, thinking, way of thinking, mind, point of view, view, viewpoint, outlook, angle, slant, side, attitude, stance, perspective, position, standpoint; theory, tenet, conclusion, verdict, estimation, thesis, hypothesis, feeling, sentiment, impression, reflections, idea, notion, assumption, speculation, conception, conviction, contention, persuasion, creed, dogma.

What’s the difference between a belief, an opinion?

It is interesting that we talk about the process of ‘believing’ but not ‘opinioning’ even though we commonly use the journey metaphor to refer to “coming to” or “arriving at” an opinion, but less often “coming to a belief”. Similarly, things can be “believable” but not “opinion-able”

There is little consensus amongst authors about the definitions or difference between the two, and the distinctions tend to be based on not very helpful metaphors which suggest beliefs are more “deep-seated” or “firmly held”.

It seems to us that all opinions involve beliefs and vice versa. Opinions can be seen as the output of beliefs but even this simple notion runs into difficulties once you examine it.

We haven’t found a way to reliably distinguish between a belief and an opinion; therefore we don’t think it is worth trying to find (arbitrary) demarcations for these concepts. In fact James has long wondered whether the notion of “a belief” is a useful idea, or a post-rationalised label. It’s doubtful “a belief” will ever be located in the brain since our neurology seems to function perfectly well without the need for this high-level abstraction.

We are going to suggest a pragmatic solution, and say an opinion is a statement about the world ‘owned’ or ‘possessed’ by someone, expressed at a certain time, in a certain place, in a certain form. Linguistically, opinions are statements that can be put into the form:

My opinion (belief, view etc) is …

I believe (think) …

At first glance, it might look like any statement could be put into this form and therefore all statements are opinions but think of times when we say something which is not actually what we believe. For example, lying, acting, pretending, being a spokesperson, supposing, acting ‘as if’, expressing someone else’s opinion, etc.

In terms of our PPRC model:

The Perceiver is the person making the statement.

The opinion is the Perceived.

The Relationship between Perceiver and Perceived is one of ‘mine’.

The Context is the setting in which the statement is said and/or the circumstances in which the opinion applies.

The relationship aspect is important given that many descriptions of opinions use metaphors such as “firmly held”, “possess”, “let go of”, “defend/attack” which hint at some kind of “ownership”.

We can have opinions about any of the Perceiver, Perceived, Relationship between, or the Context. And we can have opinions about opinions, etc.

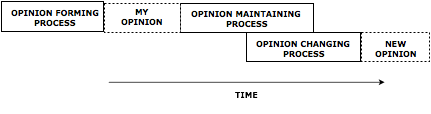

In its simplest form we assume the process of forming, maintaining and changing opinions has this kind of sequence:

By our definition, we don’t need to express an opinion externally for it to count as an opinion, since we can make the statement to ourselves. How else would we know what our opinions were?

This raises the question, do we have ‘unconscious opinions’? Opinions of which we have no knowledge?

Dilts' belief change cycle

Roberts Dilts maintains:

“People often consider the process of changing beliefs to be difficult and effortful. And yet, the fact remains that people naturally and spontaneously change dozens if not hundreds of beliefs during their life. Perhaps the difficulty is that when we consciously attempt to change our beliefs, we do so in a way that does not respect the natural cycle of belief change. We try to change our beliefs by “repressing” them or fighting with them. According to the theory of self organization, beliefs would change through a natural cycle in which the parts of a person’s system which hold the existing belief in place become destabilized. A belief could be considered a type of high level attractor around which the system organizes. When the system is destabilized, the new belief may be brought in without conflict or violence. The system may then be allowed to restabilize around a new point of balance or homeostasis.”

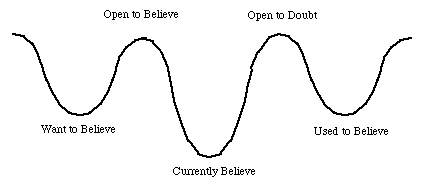

His “Landscape of Natural Belief Change Cycle” has five stages:

It highlights two important ‘threshold’ stages: “open to believe” and “open to doubt”.

The process is geared to a conscious change rather than the more generic version our diagram above. And Robert has created a walking belief change process based on this cycle. Interestingly, it contains a option to work symbolically:

The symbolic belief change cycle involves creating symbols for each of the states that make up the belief change ‘landscape’. When coming up with the symbols, it is important to keep in mind that they do not need to ‘logically’ relate to each other in any way. They should just simply emerge from your unconscious. It is not necessary that they make any sense at first.

We know of a couple of methods that could facilitate this process cleanly!

Unconscious opinions?

If a person truly believes their opinion but does something contrary to that opinion, does that suggest they have a different unconscious opinion? This is the kind of post-rationalisation we mentioned earlier. In our work as therapists we have seen the dangers this kind of thinking creates. People come to us saying “I want to get rid of my self-sabatour”. And how do you know you have a self-sabatour? “I must have because I never succeed at what I set out to do.” We have met people who have spent years in therapy trying to rid themselves of “limiting beliefs” they surmise they must have because they are not rich, famous or whatever. Chances are, learning some new more effective behaviours would be more productive.

Of course we recognise opinions about ourselves have an effect, and we can get carried away with the idea. For example, as early as 1989 the University of California assembled a team to review the Social Importance Of Self-Esteem. It concluded, “the association between self-esteem and its expected consequences are mixed, insignificant or absent.” An opinion that has had little effect on the growth of the esteeming movement.

The trouble with the notion of unconscious opinions is that they can only be inferred. In the non-organic physical domain we tend to think of each event as being caused by something else. Scientists inferred the existence of Quarks from the ‘trace’ they left behind. But in the organic domain of neurology and the non-physical domain of the mind, the idea of direct cause-effect breaks down.

Inferring beliefs from behaviour assumes a top-down view of the mind-body. Young children presumably start out acting as if the world is flat, and if you ask them, they may well agree, but did they have that opinion before you asked? Or are they just responding to the local environment? It seems strange to think of children having opinions before they have language. Sure they express their pain and pleasure, but does that mean they have unconscious opinions?

Just as behaviourism taken to extremes led psychology down a blind ally, so can cognitivism.

Others’ opinions

Susan Sontag in her 2001 Jerusalem Prize acceptance speech, published as The Conscience of Words, maintained:

There is something vulgar about public dissemination of opinions on matters about which one does not have extensive first-hand knowledge. If I speak of what I do not know, or know hastily, this is mere opinion-mongering … The problem with opinions is that one is stuck with them.

A writer ought not to be an opinion-machine… The writer’s first job is not to have opinions but to tell the truth … and refuse to be an accomplice of lies and misinformation. Literature is the house of nuance and contrariness against the voices of simplification.

David McRaney uses the backfire effect to explain the longevity of opinions, for example those held by the 40% of Americans who, despite the evidence, say the world is about 6,000 years old:

Once something is added to your collection of beliefs, you protect it from harm. You do this instinctively and unconsciously when confronted with attitude-inconsistent information. Just as confirmation bias shields you when you actively seek information, the backfire effect defends you when the information seeks you, when it blindsides you. Coming or going, you stick to your beliefs instead of questioning them. When someone tries to correct you, tries to dilute your misconceptions, it backfires and strengthens those misconceptions instead. Over time, the backfire effect makes you less skeptical of those things that allow you to continue seeing your beliefs and attitudes as true and proper.

Maria Popova decided that one the seven most important things she learned in the first seven years of producing the excellent Brain Pickings was to “Allow yourself the uncomfortable luxury of changing your mind”. She goes on to say:

It’s a conundrum most of us grapple with — on the one hand, the awareness that personal growth means transcending our smaller selves as we reach for a more dimensional, intelligent, and enlightened understanding of the world, and on the other hand, the excruciating growing pains of evolving or completely abandoning our former, more inferior beliefs as we integrate new knowledge and insight into our comprehension of how life works. That discomfort, in fact, can be so intolerable that we often go to great lengths to disguise or deny our changing beliefs by paying less attention to information that contradicts our present convictions and more to that which confirms them. In other words, we fail the fifth tenet of Carl Sagan’s timelessly brilliant and necessary Baloney Detection Kit for critical thinking: “Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours.”

Knowing you are wrong

We went to see The Majority at The National Theatre where the audience gets to vote on propositions posed by the author and presenter, Rob Drummond. The result of the votes to some extent determine the direction of the production. Audience members give their opinion (always in a yes/no format) and the majority vote rules. Some of the decisions had real-world consequences, for example the first vote was whether to let late-comers in to the performance. Surprisingly, the majority of the largely ‘liberal’ audience (we voted on it!), voted ‘no’ and we watched CCTV images of people being turned away.

Despite Drummond’s knack of asking leading and ambiguous questions it was a thought-provoking evening since many of the questions involved ethical dilemmas, including several versions of the famous “trolley problem” thought experiment. The results showed that people make different moral decisions when details in the context change, and these decisions involve more than a ‘rational calculus’ of pros and cons.

However, the most thought-provoking and memorable question Drummond asked was: “What does it feel like to be wrong?”. He clarified this by saying, “Not finding out that you were wrong, but knowing you are wrong, just like you can know you are right?”

The section on Dilts’ belief change cycle was added after the workshop.