This blog first appeared in the February 2013 newsletter of the SerenA project whose aim is “to transform research processes by proactively creating surprising connection opportunities. We will deliver novel technologies, methods and evaluation techniques for supporting serendipitous interactions in the research arena.”

It’s clear why researchers, scientists, inventors and entrepreneurs would be interested in serendipity, but why would a couple of psychotherapists?

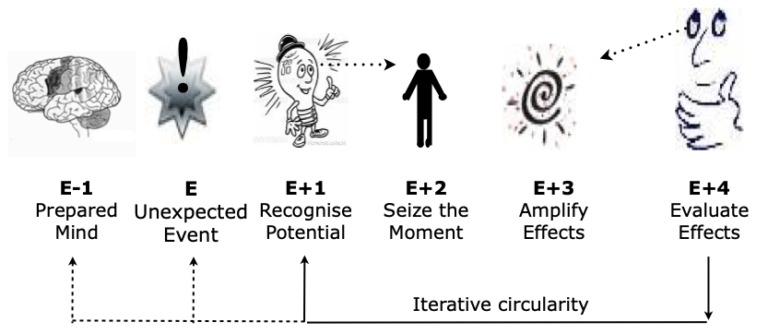

When we think of serendipity, the sensational examples catch the eye: vulcanisation, velcro and viagra for instance. We tend to focus on the dramatic moment when someone realises the heating of rubber with sulphur produces a durable material, that burs could be a kind of fastening, and that the side-effect of a heart drug could be, well, massive. Although the ‘ah-ha’ moments get all the press, they are only a small part of the serendipity process that Penny Tompkins and I mapped into six stages:

It occurred to us that the process of serendipity is a kind of fractal – it retains its basic structure at a wide range of scales.

Serendipity is a feature of self-organising systems. While serendipity appeals to our love of the mysteries in life, at its most basic it is a process for utilising the unexpected. Species that do not have enough ways to utilise chance events generated by the environment become extinct. Evolution can therefore be seen as serendipity-in-action. And so can personal development.

While people are naturally drawn to sensational examples, there are many more instances of serendipity at the personal level, especially in emergent, autogenic and ‘clean’ methodologies like the one we use – Symbolic Modelling. We regularly see our therapy clients go through a similar process and supporting them to maximise serendipity is one the most important parts of our work.

Features of the physical world that are converted into features of the mental realm are known as metaphors. Advances in cognitive science over the last thirty years have shown that much of our word, thought and deed is steeped in metaphor. The metaphorical world of the mind is our specialism and twenty years as psychotherapists has shown us that you cannot manufacture serendipity – but you can encourage the conditions before, during and after a potentially serendipitous event.

Preparing the mind involves noticing what is happening, exploring connections, being open and patient – a process we call ‘active waiting’. At some moment the unexpected happens when the client is surprised by the workings of his or her own mind. As in science, the most exciting exclamation in psychotherapy is, as Isaac Asimov said, not “Eureka!” but “That’s funny …”.

However, insight is not enough – information is not transformation. Once the surprising has been noticed and attended to, due diligence is required before the metaphor returns to influence the physical world. Applying insight to the real world, iteratively testing, evaluating and learning by trial and feedback happens over weeks, months and sometimes years. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of The Black Swan, calls this process “stochastic tinkering”.

One of our clients, Yara, had anxiety about presenting to groups. She said it was like butterflies in her stomach – nothing unusual in that you might think – but Yara had so many butterflies she was either unable to present at all, or if she tried it was such a disaster it only reinforced her anxiety next time.

In the session, the preparation phase (E-1) included Yara discovering that the problem was not that she had too many butterflies in her stomach but that one ringleader was causing most of her anxiety. Not only that but for Yara’s anxiety to lessen that particular butterfly had to open its wings and fly out of her mouth – but it couldn’t. The serendipitous event (E) occurred when, to her surprise, she realised that there were just enough other butterflies that if they all stood in a line and on the signal ‘go’ flapped their wings in unison, they could create sufficient updraft to propel the ringleader up and out of her mouth! She seized the moment (E+2) by enacting the metaphorical expelling. In future, when Yara had to present she repeated her personalised ritual of using the other butterflies to expel the ringleader, thereby amplifying the effects (E+3) of the original insight. It wasn’t difficult for her to evaluate (E+4) that she found it easier and easier to talk to groups. Eventually, the process became automatic until now all Yara experiences are little butterflies before a presentation.

James Lawley co-author of Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling is an independent researcher independent.academia.edu/JLawley and partner in The Developing Company.

The above blog is an extract from: Maximising Serendipity: The art of recognising and fostering unexpected potential – A Systemic Approach to Change (2008/2011), James Lawley and Penny Tompkins. Download from academia.edu/1836363/ or cleanlanguage.com/maximising-serendipity/