Published in The CAPA Quarterly, Issue 1, 2011, pp. 20-25.

A book on psychotherapy called Metaphors in Mind calls on therapists to work with their patients’ metaphors like: “I have a sensitive radar for insults” and “I’m trapped behind a door”.

Steven Pinker, The Stuff of Thought

In the last 30 years, the research of many cognitive scientists and linguists has revolutionised our understanding of metaphor and the role it plays in embodied cognition. Four key findings have been:

Metaphor is far more common in everyday language than has previously been realised. People often use one metaphor for every 10 to 25 words—that’s about six metaphors a minute (Cameron 2008).

“In all aspects of life … we define our reality in terms of metaphors and then proceed to act on the basis of the metaphors. We draw inferences, set goals, make commitments, and execute plans, all on the basis of … metaphor.” (Lakoff & Johnson 1980, p 158).

It is next to impossible to describe internal states, abstract ideas and complex notions without using metaphor, yet speaker and listener are mostly not conscious of the metaphors being used (Lakoff & Johnson 1999).

Metaphors are not arbitrary. They are used systematically and are mostly drawn from how people experience their bodies and how they interact with their environment (Kovecses 2002).

James Geary concludes that “Our bodies prime our metaphors, and our metaphors prime how we think and act” (Geary 2011, p 99).

Modern metaphor

Cognitive Linguists distinguish metaphor from other linguistic forms by its two-ness. A metaphor is an expression where one experience is used to describe, understand, and reason about another kind of experience (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). For example, ‘being punched in the stomach’ might be used metaphorically to describe a physical symptom of anxiety. As a rule, metaphors are drawn from everyday embodied experience in order to shed light on abstract or difficult-to-describe experiences. Thus a client referred to their lethargy as like being ‘stapled to the bed’.

While metaphor is commonly thought of as a linguistic device, people also use a huge range of nonverbal metaphors: they do this through gesture, posture, facial expression, etc. (e.g. a client discovers that a finger held across the lips is symbolic of an injunction to ‘keep the peace’); and through physical symptoms (e.g. excess weight is revealed to be a kind of body armour).

David Grove’s approach

In the 1980s, New Zealand therapist David Grove discovered three things. First, all his clients used metaphor to describe the nature of their problems. Second, he could not ask ordinary questions when working with their metaphors. If a client says, “It’s like I’m going through the dark night of the soul,” it was no good asking, “Oh, what night was that?” Instead, Grove devised an approach which preserved the exact language of a client’s metaphor and invited it to “confess it’s strengths”. He called this Clean Language. His third discovery was that if he worked entirely within the logic of the metaphor, profound changes often occurred of their own accord (Grove & Panzer 1989).

Grove’s approach can be distinguished from other metaphor and visualisation processes because it relies on the client, and only the client, to identify and evolve his own metaphors for distress and health. Also, Clean Language prevents the therapist from (unwittingly) imposing her own metaphors and constructs on the client’s inner world. While metaphors are commonly represented as words and images, his approach incorporates metaphors expressed by feelings, gestures, sounds, drawings, physical objects, etc. One fascinating aspect of Grove’s therapeutic wizardry was his use of Clean Language to communicate directly with client’s nonverbal expressions and their physical symptoms.

See the sidebar [below] for a summary of Clean Language Guidelines for working with clients’ nonverbal expressions and physical symptoms. A comprehensive description is in our systemisation of Grove’s work, Metaphors in Mind: Transformation Through Symbolic Modelling (Lawley & Tompkins 2000).

Nonverbal expression

Nonverbal communication is a natural, universal, and mostly out-of-awareness process. Recent research suggests that as much as 90 percent of speech is accompanied by gestures of some kind (McNeill 2005). Grove realised this and postulated:

In every gesture, and particularly in obsessional gestures and tics and those funny idiosyncratic movements, is encoded the entire history of that behaviour. It contains your whole psychological history in exactly the same way that every cell in your body contains your whole biological history.

(Grove interviewed by Tompkins & Lawley 1996).

Below, we describe how psychotherapists and counsellors can use their voices and bodies to honour and utilise ways clients express themselves nonverbally via:

(1) a mindbody-space

(2) the body as metaphor

(3) physical symptoms.

Mindbody space

Just as our bodies learned to orientate in physical space, we also learned to orientate in the mind- space of our inner perceptual world. You can think of clients having a perceptual space around and within themselves. Their spatial metaphors—the most common metaphors in all languages (Pinker 1988) — and their bodies will indicate where symbols are, in what direction these symbols move, and how they interact. It is the relationship between client and mindbody-space that prompts their bodies to dance within its perceptual theatre. When a client’s mindbody-space contains symbolic content, we call it a metaphor landscape.

Aligning to a client’s mindbody-space

Given the chance, clients unconsciously orientate their bodies to their physical surroundings in such a way that windows, doors, mirrors, shadows, etc. correspond to symbols in their metaphor landscape. We start each session by asking clients where they would like to sit in the room and where they would like us to be. This gives them an opportunity to align their perceptual and physical space and place themselves where they instinctively feel most comfortable and safe. It also sends a meta-message: for the duration of the session we are going to set aside our perceptual space in favour of yours. As Grove said, “space will become your co-therapist if you pay it due regard” (personal communication 1998).

Since you want to keep clients mindful of their metaphor landscape, it is vital that your marking of space aligns with their perceptual space and not yours. This is an unusual thing to do and requires you to notice how clients use their bodies to indicate the location of symbols within and outside their bodies. Then you can refer to these symbols as if they exist in those places — which, for the client, they do. When a client follows your hand gesture, glance or head point she should be led to the precise location of one of her symbols. By making your movements congruent with her perceptual space the client becomes familiar with how her inner world operates. For example:

Client: It’s scary.

Therapist: And it’s scary. And when it’s scary, where is it scary?

C: [points down to his right]

T: And when scary [point down to client’s right], whereabouts? [point down to client’s right]?

C: Down there. [points with right foot]

T: And when down there [looking to where right foot pointed], whereabouts down there? [continuing to look]

C: About 6 inches away.

T: And when scary is about 6 inches away there [looks there] that’s scary like what?

C: Like standing at the edge of a sheer drop.

To keep your language ‘clean’ it is preferable, as in this example, to reference a client’s behaviour nonverbally until they have converted it into words. This encourages symbols to lay claim to their own “patch of perceptual real estate,” as Grove referred to it, and in this way the client’s space becomes “psychoactive”.

[Note: The Clean Language questions in the above transcript have been italicised to make it easier to see the way they are formatted.]

Lines of sight

Another important nonverbal indicator of a symbol’s location in a client’s mindbody-space is a ‘line of sight’. By noticing where clients look and the focal point of their gaze you can gather information about the location of symbols inhabiting their metaphor landscape.

Lines of sight are most easily observed when the client fixes his eyes in one particular direction (such as staring out of a window), or at one particular object (e.g. a mirror, book, door handle), or is transfixed by a pattern or shape (e.g. a spot on the carpet, wallpaper motif, shadow) or gazes de-focused into space. However, even a momentary glance into a corner or over the shoulder is unlikely to be a random or meaningless act, but rather a response to the configuration of his symbolic world.

A client may also orientate his body and view to avoid looking at a particular space or direction. For example, a client entered our consulting room and sat at the right-most end of a sofa. He crossed his legs and angled them to his right. His shoulders inclined right as well. For most of the session, he held his left hand beside his left eye, like a horse’s blinker. When his hand momentarily dropped away he glanced to his left, and was asked, “And where are you going when you go there? [looking along the client’s line of sight]” He looked to his left for a few seconds and a massive sob emerged from deep within him. When he had recovered his breath, he said, “Oh God, there’s something there [glance to left] and I don’t know what it is. I haven’t been there in a very long time. If I look there, I will be trapped and it will be compulsive viewing.” Later the client realised that wherever possible, in meetings, walking down the street, at home he would arrange to have people he was with on his right.

Given the choice, where a client sits and how he orientates his body will often be determined by his dominant lines of sight. Investigating these can reveal information that would otherwise be unavailable to his conscious mind.

Body as metaphor

As well as delineating and interacting with their perceptual space, clients’ bodies express all sorts of other symbolic messages. Nonverbal metaphors can be expressed by the arrangement of any part of a client’s body, by a particular posture, by an idiosyncratic movement, or by the way he or she interacts with physical objects.

We recommend you see clients’ behaviour as an expression of symbolic patterning that helps them make sense of their interior worlds, rather than as ‘body language’ to be read. By making a body expression the focus of a Clean Language question, this patterning can be explored and, if appropriate, named by the client (usually with a metaphor). The therapist simply asks, “And what kind of [replicate client’s nonverbal expression] is that?” Grove noted that nonverbal metaphors have a “short half-life,” so questions about them must be asked while the client is doing the behaviour, or immediately afterward.

For example, at his first session, a client delivered an unbroken half-hour description of his predicament. He ended with, “So that’s how it is,” and looked up expectantly. He was then asked, “And so that’s how it is. And when that’s how it is, that’s how it is like what?” He looked away, his head turned to the left, chin pointed up high. While he was considering the question, his mouth started to open and close in a rhythmical fashion without sound. He was still deep in thought when he was asked, “And when [replicate angle of head and mouth movement] that’s like what?” The client returned to the mouthing movement a few times and said, “I feel like a goldfish coming up for air in a de-oxygenated pond.” He had captured his entire predicament in a single paradoxical metaphor; and his body had acted it out before he was conscious of it. Now he could work with the metaphor rather than swimming round and round, suffocating in the detail of his description.

Sometimes clients cannot describe their experiences in words because they were encoded pre- verbally, or related to an unspeakable traumatic event, or connected with a mystical experience. In such cases, Clean Language is an effective means for direct communication with nonverbal behaviour without the clients ever needing to express themselves in ‘ordinary’ words.

Physical symptoms

The use of metaphor and symbol in healing stretches back thousands of years. Today autogenic (self-generated) metaphor has been found to be particularly useful in “functional or stress-related illnesses, those in which no specific micro-organism has been identified as the source of physiological breakdown. It is estimated that 50 to 80 per cent of all physical illnesses requiring medical attention are stress-related or functional in nature” (Hejmadi & Lyall 1991).

Below we describe how Symbolic Modelling can be used to explore the nature of physical symptoms and to promote healing.

Metaphor in health consultations

People often use metaphor spontaneously in conversation to describe their symptoms. A study of the metaphors used by doctors and patients in the UK recorded 373 consultations of 39 medical practitioners. They analysed the 965 different metaphors used and concluded that “there were some clear distinctions between doctor and patient metaphors” (Skelton, et al 2002). Doctors tended to use metaphors that assume the body is a machine (the urinary tract was the ‘waterworks’, bodies could be ‘repaired’, joints suffer ‘wear and tear’); illness is a puzzle (symptoms are ‘clues’ to ‘problems’ that have to be ‘solved’); and a doctor is a controller (they ‘administer’ medication to ‘manage’ symptoms and ‘control’ disease).

Patient metaphors, on the other hand, were more vivid, expressive, and idiosyncratic (‘It’s like Satan’s got into her’, ‘I’m the cotton wool man’, ‘It’s like a Chinese burn, it just gets tighter and tighter’, ‘It’s as though my body has been pummelled’). Patients used embodied metaphors such as ‘dull’, ‘stabbing’, and ‘sharp’ to describe aches and pains, but these words were not used by the doctors.

From this we can conclude that doctors and their patients use different languages. No wonder so many patients do not feel heard, and that in the USA “more hospital patients die each year from preventable medical errors … than from breast cancer or motor vehicle accidents; more than half of those deaths are preventable … Errors result from prescribing mishaps, communication gaps and a distracted staff” (Cohen, et al. 2001 our italics).

Although patients spontaneously use metaphor to describe their symptoms, sometimes they need to be invited to use such language. While giving a Healthy Language course for a group of nurses who specialised in Multiple Sclerosis, we were told that their patients often had difficulty describing the bizarre nature of their symptoms. We suggested they ask them, ‘And when it’s difficult to describe your symptoms, those symptoms are like what?’ When the nurses asked this question, they got responses such as “It’s like ants running all over my body” and “It’s like cheese wire wrapped round my legs.” Further questions, such as ‘And is there anything else about that [patient’s metaphor]?’ or ‘And what kind of [patient’s metaphor] is that?’ encouraged the patients to describe their strange sensations in greater detail. The nurses were surprised at just how relieved the patients felt when they could explain their symptoms in this way. Some patients said it was the first time they felt someone had really understood what it was like to experience their illness.

Similarly, therapy clients can benefit from having metaphors for their distress elicited, developed. and evolved into metaphors for health. Clean Language not only preserves the client’s description, it prevents practitioners (like the UK doctors) from introducing their personal preferences for certain types of metaphor. Because the therapist or counsellor does not introduce any content, rather than ‘guided visualisation’ the approach is more ‘accompanied exploration’.

As many have discovered, metaphor can play a vital role in the healing process. Through Symbolic Modelling,1 the conflict, imbalance, or dis-ease inherent in the client’s metaphor finds its resolution in unexpected and organic ways. When this happens, the individual usually experiences a corresponding change in her symptoms; sometimes immediately, and sometimes in the following days or weeks.

A case study: From a cross to a willow

The following account was written by a client during a workshop which used a combination of Symbolic Modelling and Pilates bodywork with participants’ physical symptoms:2

I had pain in my upper back that had started a year before I finished writing my book. I so wanted to finish it that I used my will to keep working even though my back was worsening.

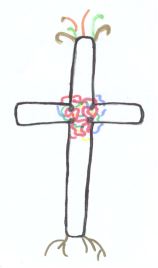

The first Clean Language question I was asked was: “And what would you like to have happen?” I replied, “I wanted to be free of this bloody pain so I could be comfortable while wearing a shoulder-strap handbag again.” I was asked questions that helped me get clear about my symptoms — I described them as “tight, grinding, abrasive” — and then I was asked “And that tight, grinding, abrasive back pain is like what?” I replied, “It’s like I have a cross on the inside of my body. My spine is the long part of the cross, and the cross bar goes through my shoulders.”

In describing this metaphor, words, pictures, and movements came naturally, unbidden by me. As I became engaged with my metaphor, I realised, “It’s not the cross that’s the problem, but the cross bar is bolted on with four huge metal bolts. There is no flexibility at all. Every time I move against one bolt, they all are put under strain and it hurts.” At this point the symbols ceased to be symbolic — they took over my reality!

Figure 1

| Q: | And what kind of cross is that cross inside your body? |

| Me: | It’s a wooden cross. |

| Q: | And is there anything else about those four huge metal bolts? |

| Me: | They refuse to move. |

| Q: | And when there’s a wooden cross and four huge metal bolts refuse to move, what would that cross like to have happen? |

| Me: | It needs to be willing to be flexible yet grounded. |

| Q: | And can it be willing to be flexible yet grounded? |

| Me: | No, the bolts won’t let it. |

| Q: | And what would bolts like to have happen when they won’t let it? |

| Me: | They need colour and support before they can let go. |

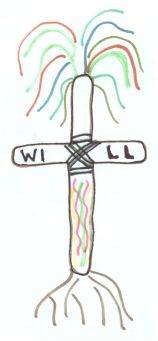

Figure 2

| Q: | And as rubber bands wrap around at all angles, what happens to a cross? |

| Me: | It’s becoming heavy on the bottom. |

| Q: | And as it becomes heavy on the bottom, then what happens? |

| Me: | It’s growing roots. |

| Q: | And as it’s growing roots, then what happens? |

| Me: | Up-and-over branches are beginning to sprout from the top. |

Figure 3

Figure 4

To conclude

It used to be thought that the mind had little or no effect on the body. The field of psychoneuroimmunology has led even the most traditional medical practitioners to acknowledge that mind and body are linked and that changes in one affect the other. It is possible to go further and to recognise that mind and body are simply different expressions of the same unity, and that all illness is, in one sense, mindbody illness, and that all healing is mindbody healing.

Metaphor and symbol are natural ways to describe symptoms and health. There are great benefits for professionals who learn how to recognise the metaphors people use, how to work within the logic of these metaphors, and how doing so can influence healing and well being.

Metaphors used by clients may be idiosyncratic but they are not random. They contain an organisation that represents the mindbody system that produced them. ‘Symbolic Modelling’ a client’s nonverbal behaviour with Clean Language is invaluable for identifying, developing and evolving client-generated metaphors. It acknowledges their way of being, provides them with information about how they make sense of their inner world, and enables them to establish a context—a Metaphor Landscape—within which changes can take place. Once this happens, their new symbols and metaphors continue working for them long after they walk out of your consulting room.

Footnotes

1 When using Symbolic Modelling with physical symptoms, we always recommend clients continue to seek advice from their medical practitioner.

2 The workshop leaders were Caitlin Walker and Catherine Saeed, trainingattention.co.uk

References

Cameron, L (2008) ‘Metaphor and Talk’ in The Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought (ed. Gibbs, R.W. Jnr).

Cohen, MR, et al (2001) ‘How to prevent medication errors’, Journal of American Academy of Physician Assistants, 14(11):47-55.

Geary, J (2011) I Is An Other: The Secret of Metaphor and How It Shapes the Way We See the World.

Grove, D & Panzer, B (1989) Resolving Traumatic Memories: Metaphors and Symbols in Psychotherapy.

Hejmadi, AV & Lyall PJ (1991) ‘Autogenic Metaphor Resolution’ in Bretto C. et al. (eds) Leaves Before the Wind.

Kovecses, Z (2002) Metaphor: A Practical Introduction.

Lakoff, G & Johnson, M (1980) Metaphors We Live By.

Lakoff, G & Johnson M (1999) Philosphy in the Flesh.

Lawley, J & Tompkins, P (2000) Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling.

McNeill, D (2005) Gesture and Thought.

Pinker, S (1998) How the Mind Works.

Pinker, S (2007) The Stuff of Thought.

Skelton JR, et al. (2002) ‘A concordance-based study of metaphoric expressions used by general practitioners and patients in consultation’, The British Journal of General Practice, 52(475): 114-118.

Tompkins, P & Lawley, J (1996) ‘And what kind of man is David Grove?’, Rapport, 33.

Sidebar

CLEAN LANGUAGE GUIDELINES

for utilising nonverbal expressions and physical symptoms

To reference a client’s nonverbal symbols:

- Use your gestures, looks and voice to denote the location of symbols in the client’s metaphor landscape from their perspective.

- Ask Clean Language questions using the following syntax:

“And when/as [‘X’], [ask clean question]?”

‘X’=replicate client’s nonverbal expression or exact wording for a physical symptom.

Use the following Clean Language questions to:

Ask for a metaphor

And … that’s ‘X’ like what?

Ask for attributes/qualities

And … is there anything else about ‘X’?

And … what kind of ‘X’ is that ‘X’?

Ask for location

And … where is ‘X’?

And … whereabouts?

Move time forward

And … then what happens?

And … what happens next?

Move time back

And … what happens just before ‘X’?

And … where could ‘X’ come from?

Ask for an intention

And … what would ‘X’ like to have happen?

Ask about a line of sight

And where are you going when you go there [look or gesture along client’s line of sight]?

A full list of Clean Language questions is available at: cleanlanguage.com