Summary

This report describes both the product of our modelling of Robert Dilts and a detailed description of the process by which we arrived at our model: ‘Selecting what is essential’.

The report is unusual in three ways:

- It provides nine video clips and a complete interview transcript, as well as other source material.

- It shows how we use Symbolic Modelling as a product modelling methodology (rather than as a therapy/coaching process).

It documents step-by-step how we constructed our model: gathering, selecting and organising information through the observation, interview and review stages.

Our hope is that by seeing how the information builds up and is organised through a number of iterations you will get a better sense of both our model of how Robert models, and our approach to modelling.

Acknowledgments

We are able to publish this report and the video clips because of the permission and generosity of Robert Dilts of NLP University; Fran Burgess and Derek Jackson of the Northern School of NLP; and Martin Snoddon of the Conflict Resource Trauma Centre (CTRC) and Northern Spring. Our appreciation also goes to Phil Swallow for video editing and web site support.

Contents

We have organised this report into twelve sections listed below.

1. Background

2. Overview of how we modelled Robert Dilts

3. First iteration: Modelling from observation

4. Second iteration: Modelling in the moment

5. Third iteration: Modelling from recordings

6. Comments on our methodology

7. Sample transcript of Robert Dilts modelling Martin Snoddon

8. Copy of Robert Dilts’ modelling notes [to be added]

9. Robert Dilts’ model of ‘Healing from the Heart’

10. Full transcript of our interview with Robert Dilts

11. List of questions we asked

12. Example of modelling from a transcript

1. Background

The material in this report has been produced and developed at three times.

Northern School of NLP, December 2006

Fran Burgess and Derek Jackson of The Northern School of NLP in England have long had a vision of ‘modelling the modellers’. As part of that vision they invited Robert Dilts to a special two-day workshop where he modelled an exemplar for the first day and presented his model to the group on the next day.

On December 6-7, 2006 about 60 people attended the two-day modelling fest. The unique format for the two days was designed by Fran and Derek:

Day 1

- Robert Dilts interviews Martin Snoddon (the exemplar) for 3 x 40-minute sessions

while the group observes - In between, Robert comments on his modelling process and answers questions

- The participants compare their observations

Day 2

- Robert presents his model and facilitates one of the participants to acquire it

- We use Symbolic Modelling to model Roberts for 40 minutes and present a first-pass model to the group

Fran Burgess models Robert for 40 minutes

NLP Conference, November 2007

The following year we decided to present our model of Robert modelling to the November 2007 NLP Conference in London organised by Jo Hogg. To prepare for that presentation we reviewed the recodings of the original event, updated and documented our model, and packaged it for a 3-hour presentation. The main focus of the presentation was the productof our modelling of Robert.

Publication on the Web, April 2010

We have eventually bowed to requests to publish our methodology – the process by which we arrived at our model. This report contains our model of Robert and the stages and iterations we went through to construct it. Therefore you get both:

and

While lots of models and techniques have been created in NLP, there is still very little about how those models were created. Our aim is to redress that balance, and to take you through an in-depth study into model creation and construction, and to some extent, acquisition.

Robert Dilts – our exemplar

Robert Dilts was one of the original group who, under the leadership of Richard Bandler and John Grinder in Santa Cruz, California in the early 1970s, started coding the processes that were to become Neuro Linguistic Programming. Robert has kept modelling at the core of his work ever since. He is the author of a number of seminal books that chart the development of NLP over the last 35 years. (See nlpu.com for a full biography and bibliography.) It was our privilege to model Robert because of our great admiration for him, and for the contribution he has made to the field of NLP.

Martin Snoddon and Robert Dilts at the Northern School of NLP

Martin Snoddon – Robert’s exemplar

Martin Snoddon runs the charity Conflict and Trauma Resource Centre (CTRC) in Belfast, and his own organisation, Northern Spring. He was chosen as an exemplar because of his background and special talents:

- Martin has spent the last 20 years working tirelessly to resolve conflict and heal trauma in Northern Ireland.

- His skills and expertise are in demand in conflict areas across the world, e.g. Kosovo, Palestine, Haiti.

- He works across all communities and religious denominations, with ex-paramilitaries, members of the security forces, non-governmental organisations and groups, and with individual victims of conflict.

- He had consistently demonstrated an ablity to work with groups who have violently opposed each other, facilitating them to engage in peaceful negotiations and reconciliation.

Our experience as modellers

Symbolic Modelling - an outline

Our modelling of Robert Dilts was the latest in a long line of modelling projects starting in 1992 when Penny modelled how highly creative people knew they had a good idea, and James modelled the internal state of Spiritual Healers while healing.

Our first large-scale project was modelling David Grove, a counselling psychologist who developed Clean Language and specialised in working with his clients’ autogenic metaphors. This took us four years and culminated in the publication of our book in 2000, Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling. After that we continued to model David’s numerous innovations until his death in 2008. It was quite a learning experience to model such a creative exemplar for 13 years.

In addition to our modelling of David Grove we have published the results of several shorter-term modelling projects related to our work. For example:

- The Problem, Remedy, Outcome Model (P.R.O.)

- Systemic Outcome Orientation (Vectoring)

Coaching in the Moment (modelled from clown teacher Vivian Gladwell)

We have also undertaken a number of commercial modelling projects, including:

- Project managers of pharmaceutical clinical trials

- Managers who support their staff’s professional development

The meeting process of a Food and Drug Administration committee (USA)

And in Modelling the Written Word we describe ten ways we have applied our modelling skills to printed text.

Currently, we are collaborating in modelling the work of the late Dutch environmentalist, Stefan Ouboter. Stefan used ‘clean’ principles to devise a method, ‘Modelling Shared Reality’, for sampling the views of key individuals across multiple organisations and communities.

[ADDED NOTE: The result of this project was published in the Journal of the Netherlands Association for Qualitative Research, Kwalon Vol 3, October 2012 and is available in English at Modelling Shared Reality]

As psychotherapists we use Symbolic Modelling as our main methodology, which means we model the individual perceptual landscape of each client. This, and our continued involvement in medium and large-scale projects means modelling has become a part of our daily lives.

Naturally our approach has been influenced by our training in modelling, in particular with Richard Bandler, Judith DeLozier, Robert Dilts & Todd Epstein, Charles Faulkner, David Gordon & Graham Dawes, John Grinder and John McWhirter. We are indebted for their groundbreaking work.

Having since taught modelling to many groups we have distilled our experience into a set of notes: How to do a Modelling Project.

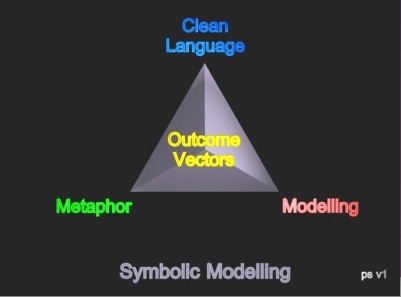

For those unfamiliar with our work, here is the briefest of outlines. Symbolic Modelling is an outcome-orientated methodology made up of three components: modelling, metaphor and David Grove’s Clean Language.

The Components of Symbolic Modelling

While Symbolic Modelling is often used as a therapeutic or coaching process it can also be used for modelling of excellence, all manner of interviews (police, research, job, defining specifications, etc.) and a variety of other applicationsin business, education and health.

A symbolic modeller pays particular attention to a person’s verbal and nonverbal metaphors. By using Clean Language questions to direct a person’s attention to particular aspects of their experience a 4-dimensional model of their internal perceptual world (a metaphor landscape) emerges. As the person discovers information (self-models) they reveal it to the symbolic modeller who then updates the model they are creating and uses it to decide what question to ask next. Symbolic Modelling is a bottom-up, iterative process. It is based on the premise that the organisation of our mind is inherently metaphoric and this influences the decisions we take and the way we live our life. We have written a number of introductory articles about Symbolic Modelling which are available our web site.Types of modelling

This report, including the video clips, show two (of the many) ways to model – Robert’s (sometimes called Analytic Modelling) and ours (Symbolic Modelling). There are many similarities and overlaps between the two; and there are two main differences:

- What the modeller pays attention to

How the modeller facilitates the exemplar to describe what they do.

For more on the theory and practice of these two methods see Robert Dilts’ Modeling with NLP, and our Metaphors in Mind:

Please note, these are only two out of a number of modelling methodologies within and outside of NLP. They all have their merits and their limitations. Our advice is to become as proficient as you can in as many of them as you are able, and to use whichever methodology best seems to fit the circumstances in which you are modelling.

[ADDED NOTE: A list of a dozen methodologies we are familiar with is available in Section 10 of How to do a Modelling Project.]

For an explanation of the NLP terms used in this report, and especially those used by Robert during his interview with us, see the online version of the Encyclopedia of Systemic NLP and NLP New Coding by Robert Dilts and Judith DeLozier.

Acquisition

Throughout the report we have included some ‘Acquisition Hints’ to help you acquire a model of Robert modelling. And, we hope that by following how we gathered the information and organised it over a number of iterations you will also be acquiring our bottom-up approach to modelling.

2. Overview of how we modelled Robert Dilts

Levels of modelling

This report is a model of our modelling of Robert Dilt’s modelling Martin Snoddon! In order to get the maximum from reading it you will need to keep in mind who is modelling whom and for what purpose. One way to organise the complexity of the information is to consider the levels of modelling involved.

| Levels of modelling (Read from the bottom-up) | See sections | |

| 3. | Our behaviour and description forms the CONTENT from which we identified the patterns of PROCESS which constitutes our model of modelling. | This whole report, particularly 2 and 6 |

| 2. | Robert’s behaviour and description forms the CONTENT from which we identified the patterns of PROCESS to construct our model. | Content: 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 Process: 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12 |

| 1. | Martin’s behaviour and description forms the CONTENT from which Robert identified the patterns of PROCESS to construct his model. | Content: 3, 7 Process: 3, 7, 8, 9 |

Our modelling process

We consider that the ‘product modelling process’ has five stages:

- Preparation

- Information gathering

- Model construction

- Testing

- Acquisition

For more on each of these stages please read our article How to do a Modelling Project.

In the first day and a half of the Northern School workshop we observed Robert Dilts going through each of the five stages while modelling Martin Snoddon. During that workshop and subsequently we went through the same five stages to model Robert, but in a different way.

Although we have numbered the Stages 1-5 modelling is not a linear process; rather it involves multiple iterations (see our article Iteration, Iteration, Iteration). To give you a sense of this we have organised this report into three major iterations:

Second iteration – Modelling in the moment

Third iteration – Modelling from recordings

Below we outline what happened during each iteration using the five stages of product modelling as a framework.

First iteration - Modelling from observation

workshop (e.g. for conscious and unconscious uptake; and to identify

which of Robert’s abilities we might want to model on Day 2)

Stage 2. Information gathering

– Observed Robert answering questions from the group

– Observed Robert present his model of ‘Healing from the Heart’ (see Robert’s model in the Appendix, Section 9)

and notes. (see our comments on the video clip in Section 3)

Second iteration - Modelling in the moment

Stage 2. Information gathering

Stage 3. Model construction

– Presented a prototype model to the group (see Section 6)

Third iteration - Modelling from recordings

– Submitted a proposal to the NLP Conference 2007

– Reviewed recorded material (see the Appendix for:

° Copy of Robert’s model in Section 9

° Full transcript of us modelling Robert in Section 10)

– Put essential patterns together into a model (see our diagrams and explanation in Section 5)

Stages 4 and 5. Testing and Acquisition

– Facilitated conference participants to acquire our model and got feedback

– Later, wrote this report (which involved many iterations)

3. First iteration: Modelling from observation

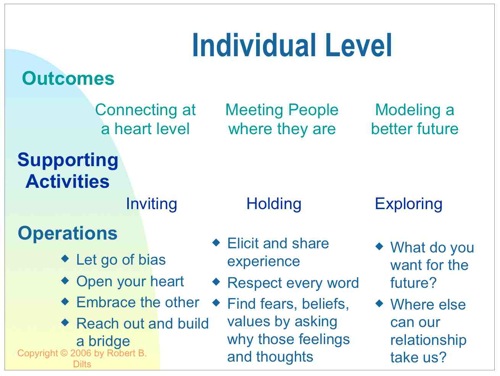

On the first day of the Northern School workshop Robert interviewed Martin for three 40-minute sessions, and in between answered questions from the audience. Overnight he constructed a model called ‘Healing from the Heart’ and summarised it in powerpoint slides which he presentated to the group. Below we reproduce one of his slides (the complete model can be seen in the Appendix, Section 9).

A slide from Robert Dilts’ model: ‘Healing from the Heart’

Having presented his model, Robert facilitated a member of the audience to acquire it; that is ‘take on’ how Martin heals from the heart.

ACQUISITION HINT

Acquiring is not about understanding a model; it is about being able to do it so that you get similar results to the exemplar.

If you want to acquire Robert’s way of modelling you can ‘take on’ what he is doing and saying as you go through this report. For example, in the first video clip you can imagine being Robert interviewing Martin – sitting and moving your body the way he does, and saying what he is says.Clip 01 - "Inviting, holding, exploring"

Robert was not given a brief of what to model from Martin’s peace and reconciliation work. During the first interview they explored what to focus on. Video Clip 01 is taken towards the end of the second interview. It starts when Martin says “It’s inviting the connection, and it’s holding the connection, and it’s exploring the connection.” (See Appendix, Section 7 for a transcript of this clip.) We chose this clip because Robert later said he immediately knew this was significant and, as you can see from the slide above it became central to his final model.

Observations on Clip 01

Below are our initial observations and inferences. We have distinguished our inferences by putting them in [square brackets].

Robert often writes while Martin is speaking. From Robert’s notes we later saw that he was recording some of Martin’s exact words. He said they were the ones he considered were labels or cues for significant parts of Martin’s process.

In this five-minute video clip Robert does the majority of the speaking. Embedded within his comments are four questions; three of them of the form, ‘How do you…?’:

How do you ‘open your heart’?

How do you ‘let go’?

This notion of ‘just being’ – so how do you do that?

The fourth question is quite different:

My guess is that you have to prepare yourself in a certain way to connect. In fact to reach out, or to invite means that you kind of have to be – in some language you might say, ‘not in your own ego’. It seems to me it’s a special place to be. You’re not trying to impose your map of the world on other people. You’re not trying to be right. You’re not trying to go, ‘I’ve got to be safe’. It seems to me there’s some quality that you have inside that allows you to do that. What would you say to that?

Robert often repeats Martin’s exact words. He also uses Martin’s words as part of his own description. Much of what Robert says is in the form of meta-comments. These can be:

- From his own perspective, e.g. “That seems to me to be very interesting …”

- Inferring about Martin’s process, e.g. “It seems like in a certain way everything else is all dependent on your capacity to open your heart.”

- To explain what he is doing [apparently to prepare Martin for what’s to come] e.g “I’ll be asking you a lot of ‘how’ questions.”

- Describing NLP or modelling e.g. “It’s a really fundamental difference that makes the difference”.

One of the effects of Roberts commenting is that it gives Martin time to think: “As you’re talking I’m thinking: What am I doing when I’m actually doing that?”

A number of times Robert starts a sentence, stops and starts another one. Also, he regularly says or asks something and then says it again in several different ways (for example see the quote above which starts “My guess is that …”).

While Robert is speaking his body often seems to be actively involved. Particularly noticeable are his gestures. He often repeats Martin’s words while pointing to and gesturing around his own body. For instance Robert asks: “How do you open your heart?” while gesturing to his own heart area.

As modellers it’s intriguing to consider: Given Robert is an expert, what is the function of his repeating, describing and commenting? We guess Robert is giving himself time to embody and take on Martin’s description, and to decide what question to ask next. What happens in the interior of Robert’s mind-body becomes clearer during our interview with him.

Observed patterns

- Multi-outcome orientated — his own, the exemplar’s, and the imagined acquirers’

- Multi-sensory (Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic)

- Multi-level — from “details of how” to “deepest drivers” of life purpose

- Multiple perspectives — we counted at least seven

- Multiple time frames — from exemplar’s history, to the interview in the present, to future acquisition

- Lots of repetition/backtracking — of words, metaphors, concepts, etc.

- High use of metaphor and analogy

- Overt and consistent demonstrating on the outside of what’s happening on the inside

Describing things in groups of three.

Robert acknowledged that to do the above requires “multi-tasking”. We think to be able to access multiple outcomes, levels and perspectives simultaneously (or to switch between them fast enough as to appear simultaneous), requires the ability to have ‘split attention’. This is vividly illustrated in the next section when Robert describes how he associates into an inner movie he has created and dissociates to watch the movie and ask himself questions about it, while continuing to interview the exemplar.

4. Second iteration: Modelling in the moment

Having observed Robert modelling Martin on the first day of the Northern School event we chose a focus for our modelling and agreed it with Robert before starting our interview. We used a process called Symbolic Modelling which we developed from our modelling of David Grove. We call the interview part ‘modelling in the moment’ because that’s exactly what we are doing: gathering information, constructing a model and testing it in real time as Robert is describing and doing it. The eight video clips below demonstrate how we did this.

Our outcome

Our modelling centred on the question: When Robert Dilts is modelling, how does he know what is essential? In other words, given everything Martin (the exemplar) said and did, how did Robert select the elements that ended up in his model and acquisition process?

We have chosen eight 2-3 minute clips from our interview, each of which highlight an element we consider essential to what Robert does. After each clip we describe some of what we noticed was significant. These clips show about half of the interview. A transcript of the entire interview is available in the Appendix, Section 10.

In this section we take you through our interview with Robert as the exemplar. You can use the eight video clips to imagine you are Robert doing what he is describing he is doing (rather than copying him as in the last section).

Clip 02 - "Guided by the feeling"

Clip 02 is from the beginning of the interview where Robert gives his “first answer” – a list of factors involved in the process of knowing what is essential:

- “You feel it” and are “guided by the feeling”.

- It is “not a cognitive analysis”.

- It is not “the words themselves, you have to tell by the meaning”.

- It has to do with “what your goal is – what you are trying to get to” the “acquisition tool or process”.

- And, “what Martin [the exemplar] is doing – his goals – to create this type of healing among people who have been in conflict and trauma situations.”

You “have to get enough of something that’s necessary and sufficient enough to produce the result”.

CLIP 03 - "Like a radar that goes beep, beep, beep"

In Clip 03 Robert describes more about his selection process:

- The feeling of significance is on the “mid-line”.

- “It is like a feeling of activation”.

- “I pay attention to my center [where] things register”.

- “I listen a lot to my center. It’s different than listening to my heart”.

- “It’s like a radar signal that goes beep, beep, beep …..”.

“In significant times the center becomes activated” with a “quality of energy”.

The metaphor “radar signal” is symbolically represented by his gesture and the beep, beep, beep, beep sound he makes. (It sounded more like a Geiger counter to us, but that’s not what Robert called it.) Like all metaphors it reveals much about a person’s inner world. Although Robert didn’t say it, the entailments of the metaphor suggest:

- A scanning process that comes from the area of the navel.

- Being able to detect what can’t be seen (Robert calls this “deep structure”).

The signal is variable (analogue) as his “beeps” change in volume, pitch and speed. This likely makes the signal highly sensitive to small changes in relative significance.

Clip 04 - "I mark it inside"

Whatever activates Robert’s center is “marked into memory” and “connected to my center”. These then “become more likely to be a part of me”. It seems Robert has a three-step selection process:

Notice a feeling of activation (indicating significance)

Mark or register what the exemplar said or did that activated the feeling.

You can see from his gestures that for Robert selecting for significance is a highly embodied process. Robert also externalises what he has selected as significant by making notes on paper, but the main marking is something that happens inside.

In this clip Robert uses his first Mozart analogy (a form of metaphor) to illustrate how notes would come to Mozart, and only those ones that he hummed were selected:

| Mozart | Robert Dilts | |

| Notes that come | = | Words of exemplar (data) |

| Feeling from tone | = | Feeling of significance |

| Notes he hummed | = | Marked as significant |

Clip 05 - "Backtracking things that have been marked"

In Clip 05 we discover there is a fourth aspect of Robert’s selecting-for-significance strategy. This involves “testing” the exemplar’s descriptions he has marked to find out: (i) “Are they still there?” (ii) “Are they still significant?” and (iii) “Do they still feel resonant?”. He does this by repeating and backtracking (a form of recapping) what he has marked by “pulling them back out” of his memory bag (à la Mozart) and noticing if he still gets his signal for significance.

Now we have the key elements of Robert’s strategy: he keeps his modelling outcomes in mind from the very beginning (i.e. to produce an acquisition tool); he keeps his attention on his center and waits for his radar-like signal to be activated by an example of significance; then he marks that bit of the exemplar’s content/process in memory by connecting it to his center. And at various times he tests whether what he has marked is still significant, by backtracking and running the whole strategy again.

Initially we were surprised just how much Robert spoke while modelling Martin. Now we know the purpose it serves. By backtracking he is running the exemplar’s process through his system and internally testing for significance over and over. Of course this also gives the exemplar a chance to confirm the accuracy of Robert’s model-in-creation – which is an external test.

Having selected, marked and tested what is significant, then what does Robert do?

Clip 06 "This fits with this"

Once Robert has marked enough significant things “they start arranging themselves”. He again draws on a Mozart analogy, this time to explain how he is noticing when things “fit”. When “two notes love each other” they are paired together. Then at a higher logical level he fits the pairs together until “there’s some kind of field created”. Thus two levels of fitting are taking place.

We surmise that Robert has already begun this process because part of “marking” involved determining whether the thing that has a feeling of significance had “resonance” with other significant things. As the fitting process progresses it “starts to involve much more cognitive mind” because now he is organising the information.

Clip 07 "Phases one, two, three"

Robert describes his process in “phases”. Congruently, the first thing he does is to make the purpose of each phase clear:

| Phase I | To identify “What is significant to explore in phase two”. |

| Phase II | “I’m still looking for what’s significant but now I’ve got more information. I’m kind of trying to fill in, that has to do with the notion of exploring a direction, also beginning to try to get a picture of what the process is.” |

| Phase III | “To construct a movie”, to discover “Can I do what he does?” and to “install it” in me. |

Robert uses the same process to model himself as he does when he models an exemplar. That is he “backtracks” what he has described before providing more detail and filling in the gaps. For instance he adds information about Phase II: the “notion of exploring a direction” and getting “a picture of what the process is.”

In Phase III Robert creates a movie of what Martin has described. Most significant is Robert’s statement “I’m getting second position, not with the Martin who is sitting here answering me, but with the Martin in my movie who was doing what he does.”

We think this distinction is vital because it is not trying to ‘be’ the exemplar in the room. Robert is saying he creates a movie of the situation Martin works in (e.g. with paramilitaries), and imagines himself in the movie doing what Martin is doing, and saying what Martin is saying.

In this way he is “installing” the strategy in himself, which means he will have “already rehearsed aspects” that will form part of the acquisition process for others.

But how does Robert know he has done enough modelling? How does he know whether what he has is “necessary and sufficient”?

Clip 08 - "Can I do it?"

Robert continues gathering information, fitting parts together and constructing the movie until he has “a feeling, a congruence” that he can do what Martin has described he does. We guess it probably takes less time for Robert to get this feeling than for most of us because of his vast experience of modelling. He doesn’t have to know exactly what the exemplar would say and do, because he is “always filling in the gaps”. All he needs is to have “a certain level of detail in that movie to fit; step into it; and then sho-o-o, and I know that my body and my words can follow, can do that chunk.”

If he doesn’t have the congruence feeling he wonders, “Where does it feel vague?” and he asks more questions to fill in gaps. Phases I, II, III are cumulative, not just sequential.

Clip 09 - "Both associated and dissociated at the same time"

In the “process of making a movie all these things start to fit together” as a unit. When that happens the “process flows” through the movie. This is a different kind of “fit” from that in Phase II because it is at a higher, more inclusive level. This is more about organising and in particular sequencing the parts that have already been fitted together.

Clip 09 also demonstrates an unexpected extra piece of Robert’s modelling process. He doesn’t just put himself into the movie he has created, at the same time he also imagines himself in the “audience” watching the movie. This is an interesting dual perceptual position. He’s in the movie as Martin, and also out in the audience watching and considering the process.

Phase IV - "Putting it together into a model"

You can now see how most of the content of each video clip relates to one of Robert’s three phases:

Phase II Clip 06

Phase III Clips 07-09

The rest of the interview related to how Robert later organised the information he had gathered during the interview with Martin. We call this ‘Phase IV’. We have not shown any clips of this since it relates less to our topic of selecting what is essential. However, you can read the transcript of the interview in the Appendix, Section 10, and see our not-yet-complete model of Phase IV in Section 6.

Although we had observed Robert modelling, and listened to his explanation of what he was doing, and listened to his answers to questions from the audience, some significant pieces in how he models had not been made explicit. Our short interview demonstrates how Symbolic Modelling can facilitate an exemplar to go beyond what they think they know.

5. Third iteration: Modelling from recordings

Having observed Robert Dilts do what he does, and having used Symbolic Modelling to interview him about how he does it, our modelling went through a third iteration. We used the source material we had gathered during the Northern School workshop to complete our modelling and produce a formal model. This required four steps:

| a. | We watched the video of our interview with Robert and reviewed what we had identified during the first and second iterations. |

| b. | We produced a verbatim transcript (including notable nonverbals) and went through it several times filtering for different kinds of information, e.g. metaphors; internal and external behaviour; desired outcomes; evidence criteria, etc. These were marked on the transcript using different coloured highlight pens. |

| c. | We organised the patterns identified in the transcript by:

[You can see an example of this step in the Appendix, Section 12.] |

| d. | We transferred information into location and systemic diagrams, continuing to prune and organise the remaining essential elements into a coherent whole, presented below. |

Our model for 'Selecting what is essential'

Overview

We started with an outcome: To model how Robert Dilts ‘selects what is essential’ when he is modelling. We ended with a model that has four phases. Phases I-III occur while interviewing the exemplar, Phase IV happens after:

I. Select what is significant

II. Fit parts together

III. Create associated/dissociated movie

IV. Arrange what is essential into a model

At first sight it might appear that we accomplished our aim with Phase I and that we could have stopped there. However a number of factors meant we continued:

As a result of modelling Robert we now make a distinction between ‘selecting what is significant’ and ‘selecting what is essential’. ‘Significance’ is required for something to be ‘essential’, but it is not the whole story. Essential only selects those significant events that constitute a minimum requirement without which the process would not work. Essential means no frills, even if those frills add value. Co-opting Robert’s language, ‘essential’ is both “necessary and sufficient” – but no more.

Robert’s selecting process does not just happen at the beginning. He is continually selecting and testing his selections with each new piece of information supplied, and with the congruence of his own imaginings. In each phase he selects for different things:

Phase I – Selects individual parts

Phase II – Selects pairs that fit together

Phase III – Selects coherent chunks that meet a high-level goal

Phase IV – Selects a minimal description from Phases I, II and III.

Also, given that Robert is one of the most prolific modellers in the field of NLP and this might be our only chance to interview him, we wanted to grab the opportunity with both hands and get as much as we could.

Our models of Phases I, II and III each contain two diagrams: Location and Process. These are two descriptions of similar information and are best ‘read’ together since the where and the how of experience are complementary.

It should be clear from the video clips that modelling for Robert is highly embodied. This is indicated by both his gestures and his embodied metaphors. The ‘location diagram’ shows where Robert experiences the various types of information in his internal perceptual space. Some of this is inside his physical body and some is in his mind-space but outside his body (see our article, When ‘Where’ Matters).

The ‘process diagram’ depicts a systemic, circular chain of events. We decided to represent Robert’s processes with systems diagrams to show his use of iterative feedback loops. An iteration applies the same process to the output of the previous iteration, over and over. In Robert’s case he uses an iterative process for gathering, selecting, marking, fitting and organising information. Phases I, II and III are not only sequential, they are also cumulative. They enable Robert to home in on what is essential and settle on a model that he knows he can enact.

Our model of Phase IV is incomplete since we didn’t observe Robert constructing his final model and it would have required more interview time to get to the internal processes behind his conceptual labels. Having said that, we included what we did get since it contains some useful information and gives a sense of Robert’s modelling process from beginning to end.

To save repeating ourselves, the annotation accompanying each diagram assumes you have read our notes accompanying the video clips in Section 4.

So far, to take on Robert-as-modeller you copied him by saying and doing what he actually said and did while interviewing Martin. Then you imagined you were saying and doing what he described he was saying and doing while he was an exemplar being interviewed. Now if you want to you can take on our model.

To take on Robert’s strategies you need to have a sense of how he makes use of his “somatic mind” and “cognitive mind”. The location and process diagrams below will help you do this. Remember the phases are cumulative: when you transition to Phase II you are still running Phase I; and in Phase III you are running both Phases I and II, just more in the background.

You may find it helpful to have someone assist you to acquire the following models. Start by using the Phase I location diagram to help you associate into Robert’s interior perspective. Then your assistant can step you round the process diagram. You will need to go round the loop several times until you sense a signal to move on to the next Phase. Your aim is, without knowing why, to do it Robert’s way as best you can and to notice what happens. Your assistant’s job will be to keep to the model and to not add in their own words, ideas or suggestions.

Prelude

Consider this …

When Mozart composed music he said that notes would come to him and sometimes he would get a feeling from the tone, and if he got the feeling he would hum those notes. Of all the notes that were coming the ones he would hum were the ones marked as significant. That’s how he selected notes. Mozart would put the notes he had marked into his bag of memory. Later he would pull them back out to test them. Are they still there? Are they still significant? Do they feel resonant? Sometimes they would feel more resonant than before.

When he had collected enough notes, all of a sudden he would start to apply rules of point and counterpoint. What notes am I going to use? He didn’t apply these rules at the beginning. Not until he’d got enough would he go: that’s got to go there and that’s got to go there. Sometimes it would feel like he’d have to change something to really capture it. That’s even more of a cognitive process. Of course Mozart was trained in the structure of music but he also had intuitions about the basic feel of music.

And finally, once Mozart got the sound organised he would say we’re going to use this instrument to play that sound.

Phase I – Select what is significant

Our two diagrams in Phase I depict where and how Robert selects, marks and tests what is significant.

Phase I provides the building blocks which get organised in Phases II, III and IV. Phase I happens continuously throughout the modelling because the exemplar might add something significant at any moment. Similarly, regularly testing against an internal criteria of significance is necessary because the model you are creating will continuously evolve with each updating. You can consider the repeating, backtracking and testing as a form of quality control. If something is still registering as significant after several testings the more likely it is an essential part of the exemplar’s process.

One of the challenges of taking on this model is getting a sense of what Robert is selecting for. He emphasised several times during the interview that although he is selecting, marking and testing words used by the exemplar (i.e. content), these are only labels or cues for bits of process or structure. The art is to remember to stay at this level.

We have already commented on the three-step nature of selecting what’s significant: attending to center, noticing when a feeling of significance is activated, then marking the triggering content in memory and making it part of you. The process diagram shows how systemic this is. It also shows the importance backtracking plays in keeping the process going.

The feeling of what is significant – the radar signal – guides the direction of your questions. This, along with your goal for modelling clearly in mind throughout, means information gathering is not a random search. Although you cannot know in advance where you are going, the guidance system gives directionality to the search and increases your hit rate when sorting the wheat from the chaff.

Phase II – Fit parts together

The process Robert uses to fit together what he is marking as significant is depicted in our two Phase II diagrams.

While Phase II “is a different information gathering process” to Phase I, you can use a similar three-step strategy:

- Attend to your center

- Notice when there is a resonance between things marked as significant

-

Capture those parts that fit together in a picture.

Robert describes how things “start to arrange themselves” and “a field is created”. It seems he doesn’t use his “cognitive mind” until the out-of-awareness arranging has progressed enough that it is ready to become conscious. Once this happens he starts to “explore a direction” which, we’d guess, enables him to “fill in” more and to test the robustness of the fits in another iterative loop.

Notice how the metaphors of “radar” and “guided” from Phase I, and “direction” and “explore” from Phase II work together as a coherent method of mapping a new territory.

Phase III – Create associated/dissociated movie

Once Robert has identified some of the significant parts of the exemplar’s process and started to fit them together he can transition to arranging everything into a movie.

We are not sure if in Phase II Robert creates one picture which contains all the significant parts that fit together or he creates a number of pictures – a “storyboard” – which naturally become a movie when there are enough frames. Either way, then he can “step in” to the exemplar in the movie.

In Section 4 we commented extensively on Robert’s ability to associate into and dissociate from the internal movie he creates. By creating an inner movie and associating into the position of the exemplar in the situation where they apply their skills, Robert is “installing” the exemplar’s process into himself. You will note that in Phase I the significant parts were already “becoming part of me”. We suspect that when pairs of significant things are “registered” in Phase II that too has the effect of installing them. If so, installation is another aspect of Robert’s strategy that happens throughout his modelling.

Although Robert mentioned “exploring a direction” in relation to Phase II, from observing him it is clear that in Phase III his questions have a definite directionality too. It seems that when bits are missing or feel vague he pursues a line of questioning around that chunk of the exemplar’s process. He continues to “figure out” and “fill in” until a feeling of congruence lets him know he can do it. Then he’s done.

Thus Phase III is essentially an extension of Phase II with three additions: sequencing of events; an associated/dissociated perspective; and an exit strategy.

Phase IV – Arranging what is essential into a model

Our model of Phase IV is less complete than Phases I, II and III because we didn’t observe Robert produce his model and we didn’t have much time to explore what he does internally during that process. This is why our description is more conceptual than the previous three phases. However we thought what we did get was useful and below we present an outline of a model.

Overview

Just as at the beginning of modelling, in Phase IV Robert is strongly focussed on his outcome: To organise what is significant in a way that is meaningful and useful:

– Arranged outside (physically and perceptually)

As with previous Phases, Phase IV starts outside of Robert’s awareness. We think it is highly likely that Phase IV processes have been operating in the background during the earlier phases. Robert becomes the recipient of this knowledge when there are enough significant things gathered and fitted together (in Phases I, II and III) that they start to fit into coherent structures; they start fitting together as a unit.

In locational terms, Robert arranges the parts of his model on a mental “workbench” in front of him, whereas his knowing that he has identified a deep structure is a felt-sense inside his body. As in the other phases his “cognitive” and “somatic” minds work in tandem.

In the most general of process terms, to construct a formal model once he has interviewed the exemplar Robert reviews his Phase III movie and his written notes, and:

- Starts with general connections

- Applies known rules/structures to fit things together as a unit

- Gets detail about activities.

Given that Robert uses iteration in Phases I, II and III we can be reasonably sure that he does the same in Phase IV. If so these processes are not to be seen as linear procedure but more as a systemic wheels within wheels process.

Let’s take a look at these processes in a little more detail:

Start with general connections

Relate things by kinds of information, e.g. goals, activities

Find links between significant things

Use visual and auditory perspectives to find:

- Nice fits – what goes with what

- Words that fit together form themselves into where they belong in a process

- Clusters of words which are clues to deeper structure

- What makes sense

(Remember, words are surface structure. They are cues/labels about a deeper process.)

xxx

Apply known rules/structures to fit things together as a unit.

It is like using a workbench

Apply:

- Process rules

- Cognitive structures, e.g. TOTE

- Principles

- Training

- Experience

Feel the deep structure of the process so that it flows through the whole model.

Get details about activities

Identify details of how to do each activity

Ask yourself: What is each activity trying to make happen?

When you look at Robert’s model of Martin in the Appendix you will see that it has been structured in a way that is congruent with the above:

General comments on Phases I, II, III and IV

Mozart analogy

After the interview Robert said the most surprising thing to him was how much he referred to Mozart for analogies of his modelling process. These helped Robert explain what he does to himself as much as to us. We did not specifically reference Mozart in our diagrams. Instead we attempted to retain the value of analogy by putting all of Robert’s references to Mozart into one preparatory story that replicates the four phases of his modelling.

Questions Robert asks himself

Central to Robert’s methodology are the questions he asks himself. We counted about 40 in the transcript of our interview – that’s over one per minute. Not only is the frequency important, so is the quality of the questions. They are ‘pure’ modelling questions which neatly dovetail with his outcome orientation.

We recommend you read through the Appendix, Section 12 and pick out the questions Robert asks himself. (We have made this easy for you by indenting them and putting them in italics.) When you look for the pattern in these questions (and the questions he imagines Mozart asks himself) you will notice that they are remarkably ‘clean’. That is, they are short, to the point and they only ask for information about what is happening with minimal presupposition outside of the context. To answer his own questions Robert has to keep modelling. Searching for the answer to each question naturally takes him towards his outcome.

Bottom-up (parts to whole) and Top-down (whole to parts)

Robert is modelling bottom-up from specific examples provided by the exemplar to create a top-down model for an acquirer (see our article, Modelling Top-down and Bottom-up):

In Phase I bits of process are selected; in Phase II he finds pairs that fit together; and in Phase III he is looking for how they fit together into a movie which can be represented as a unit in Phase IV. Each phase, to use Ken Wilbur’s term, “transcends and includes” the previous phases.

In Phase IV however Robert does something different. He finds general connections, applies known rules and then identifies the detailed ‘how to’ of each activity. This culminates in a physical representation of his model. So Phase IV is more of a top-down methodology. It starts at a high level and works its way down to a specific representation.

We characterise this bottom-up and then top-down process in the following diagram.

Levels of “fit”

The transcript and video clips demonstrate another common phenomenon in modelling: homonymy – when the same word means different things. During the interview Robert uses the word “fit” 20 times, but not always in the same way. It took a diligent analysis to differentiate the meanings. We think there is a difference between the “fit” in Phase II, the “fit” in Phase III, and the “fit” in Phase IV. “Fit” in Phase II and Phase III means fitting parts together and then fitting the fitted parts together. These form the basis for the “fit” in Phase IV which is at least one logical level higher, at the whole-model level:

Phase II fits parts together

Phase III fits those fitted parts into a movie

Phase IV ensures a fit with the structure of the whole model.

In this way Robert covers several fundamental ways of organising experience: functional relationship between attributes; temporal relationship between events; and part-whole relationships.

Agent and recipient

While modelling is an active process requiring a large degree of agency on behalf of the modeller, much of what Robert does has a more passive ‘it’s just happening’ feel to it. It appears Robert is as much a recipient of signals as he is an active agent. He experiences these signals or cues as feelings, embodied fits, intuitions, thinking “that’s it”, and congruence. These are not emotions; rather they are felt-senses or kinesthetic representations or embodied knowledge.

On one hand, Robert leaves the identification of what is significant to the activation of his radar signal and is guided by that feeling. Then things fit together and at some point start to arrange themselves. This creates a field and the words start to form themselves into where they belong in the structure. On the other hand, Robert actively gets involved in setting his goals and intent, listening to his center, and doing external behaviours such as note taking, backtracking and asking questions. Later he actively tries to capture what has been brought to his attention first in a picture, and then in a movie – if necessary filling in when something feels vague or is missing.

By the time he gets to Phase IV, Robert is mostly an active agent: relating things; finding links; using visual and auditory perspectives; using a workbench; and applying rules, cognitive structures, principles, training and experience.

This dual agent/recipient function can be seen by an analysis of Robert’s metaphors:

| Active Agent | Passive Recipient |

| I’ve got to find out what’s essential to create something | [I’m] guided by the feeling of what’s essential |

| I listen a lot to my center | In significant times the center becomes activated |

| I’m backtracking and pulling out those things that have been marked | It’s like a radar signal that goes beep, beep, beep |

| Looking for what’s useful and what’s meaningful | The radar is going to go ‘this thing is significant’ |

| I’m trying to get a picture | There’s some kind of a field created by these different things |

| I’m trying to fill in | Do these two notes love each other? |

| To really capture what it is | They start arranging themselves |

| I’m trying to construct a movie | A phase where things start fitting |

| I’m already installing it | Lots of data that comes |

| [I] figure out, where does this movie stop? Where does it feel vague? | Words start forming themselves into where they belong |

| I’m going to register that | Something will register |

| Mozart would start to apply rules | Things start to fit into a structure |

In a parallel process the relationship between Robert’s “somatic mind” and his “cognitive mind” changes during the modelling. In Phase I, Robert’s modelling mainly involves somatic mind with little or no cognitive mind. In Phase II and III there is a “interplay” between somatic and cognitive minds. By the time he gets to Phase IV his process is mostly cognitive, organising what he has previously identified somatically.

Now you have an overall sense of what Robert does you can rehearse his behaviours with more of a context for how they work together to produce excellent modelling. You can also return to Sections 3 and 4 (and the transcripts in the Appendix) and review the information more cognitively. Since we do not have a complete model of Robert’s method of modelling you will have to fill in bits – just like he does!

After you have acquired a model as close as you can to the way Robert does it, you can consider adjusting some of the elements to make better use of your existing resources. For example, your significance signal might be located somewhere else and it may not be like the beep, beep, beep, radar signal Robert uses. You can substitute your own location and metaphor as long as it has enough of the same characteristics that it performs the same function as in the model.

What now?

We have completed the tour through our model of Robert modelling. That journey involved three iterations, each one visiting the same material with fresh eyes but with an accumulated knowledge. Next we turn the spotlight on our methodology.

6. Comments on our methodology

Up to now we have presented the product of our modelling of Robert. Now we take a step back and look at the process by which we arrived at that model. We conclude with a review of Symbolic Modelling as a product modelling methodology.

You can now turn your attention from modelling Robert to modelling our methodology. We haven’t produced a formal model of our approach although our notes of How to do a Modelling Project go some way towards this. You can get a sense of what we did in two ways: reviewing the format of this report since it’s structure replicates our process; and using our description below to imagine yourself doing what we did.

First iteration: Modelling from observation

We have studied with Robert and read all of his books so at some level we will have previously created some kind of mental model of him. Therefore while observing him model Martin our aim was, as much as possible, to set aside our preconceived ideas and to discover something new. We did this by alternating between a not-knowing unconscious-uptake state and a more conscious musing-about-what-is-happening state. Both of these states share an intention to not jump to a conclusion. In the first, the intention is just to receive and take on; in the second it is to muse cleanly (see Judith DeLozier’s article, Mastery, New Coding and Systemic NLP; and our article, A Model of Musing).

In the breaks and overnight we downloaded our initial impressions and compared our notes. However at this stage most of our model construction was happening out of awareness. By the end of the day we were in a position to describe some of what we saw and to identify a few general patterns in the way Robert does ‘Robert modelling’. We consider the list at the end of Section 3 to be a set of general capacities inherent in his approach. Although we detected some of these patterns during the first iteration we also added to and reorganised the list throughout the second and third iterations.

We may have had some intuitions and had identified some patterns, but we didn’t have a model yet.

Second iteration: Modelling in-the-moment

We chose to model the topic of ‘selecting what is essential’ because it is fundamental to all modelling methodologies. Every modeller has to handle a mass of information, much of which is not directly relevant to their outcome. And while it is possible to construct an effective model out of non-essential bits, it will be neither efficient nor elegant.

Since we had observed Robert’s exterior behaviour the previous day, our aim when interviewing him was to invite him to attend more and more to his interior perceptual mind-body space. We wanted to find out what he did on the inside while he was doing what we had observed on the outside. Having heard him answer many questions from the group we also wanted to get to those aspects of his modelling which he had not mentioned.

When we sat down with Robert we didn’t have a plan of the questions we wanted to ask. Rather we started with a general aim to identify and locate some of his key symbols, and to find out how they worked together to produce the ability known as ‘selecting what is essential’. After that the direction of our questions was guided by the emerging organisation of the information – and our desired outcome.

An important point to note is that we did not ‘take on’ Robert’s process, i.e. we did not put it in our body and in our perceptual space like Robert does when he is modelling. Instead we constructed our model in Robert’s perceptual space, keeping the elements (symbols) where they were located from his perspective. That’s why we gestured to his body/space, and not ours.

Also we did not do as much backtracking and meta-commenting as Robert did when he was interviewing Martin. In part this is because Robert-as-exemplar was doing a lot of backtracking himself, and in part because we are doing a form of ‘internal backtracking’. We visit the symbols in the exemplar’s inner metaphor landscape and muse on them so we can ask enough intelligent questions to keep them revealing more of their process. From our point of view this has a similar effect to external backtracking: it keeps the modeller connected and close to the totality of the information being presented; and it has a different effect on the exemplar and on the flow of the interview.

By the end of the interview we still didn’t have a complete model, but our notes were good enough to present a first-pass model to the group. This consisted of a single locational diagram covering the key symbols we had jotted down in our notes and a verbal description of the main bits of Robert’s process we had identified so far:

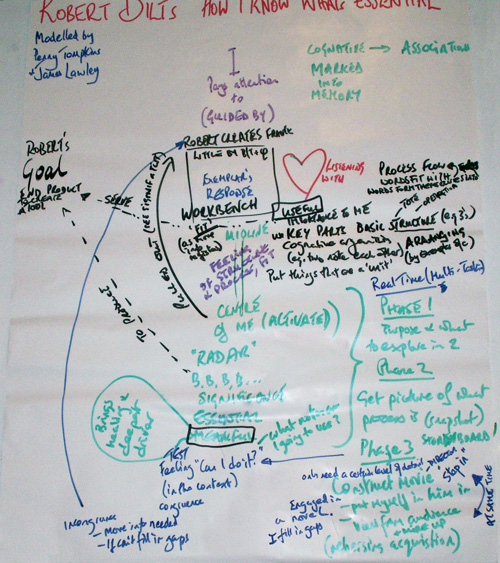

Penny Tompkins and James Lawley’s first-pass model of: ‘Robert Dilts: How I know what’s Essential’

Although we had a sense of the iterative nature of Robert’s approach, we didn’t have a conscious representation of how it all worked together. That only came in the third iteration.

Having taught modelling for decades, Robert is obviously not your average exemplar. Many of his answers contained a huge amount of information neatly packaged. This created somewhat of a dilemma. Often what an exemplar does is so out of their awareness that facilitating them to describe what they do is a painstaking process. Not so with Robert. The challenge for us as modellers was to cope with the concentration of information – only some of which was getting into the model we were constructing around him – and to continue to ask questions which would shine light into the few unlit corners of his mind. When Robert said “the most honest answer is I don’t know” and “You just do it”, he is saying what all exemplars say when they reach the edge of their meta-cognitive map. The purpose of our questions was to tease out his ‘tacit knowledge’.

It is also interesting to note that while interviewing Robert we were faced with what Gregory Bateson might have called a code-congruency dilemma. Not only were we trying to acquire a model of Robert modelling, we were attempting to do it by demonstrating our model of modelling. Fran Burgess has noted that expert modellers like to be modelled with their own methodology. To be congruent with Robert’s approach we would have done lots more backtracking, more preparatory explaining and more overtly taking on his model in our bodies – just as he did. However, our outcome was to provide the group with a different description of modelling. So most of the time we refrained from doing that in order to more clearly demonstrate our approach. One potential downside was that at times it seemed Robert wasn’t getting the cues from us that would have let him know we ‘got’ what he was describing.

Third iteration: Modelling from recordings

The detailed analysis and model construction in the third iteration involved going through the video and transcripts over and over. We distilled what was essential and arranged it into a model. Getting to this stage involved both a quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Our quantitative analysis was very simple and yet gave us a sense of scale. (See our article, Big Fish in A Small Pond.) For example we looked at:

- The proportion of words spoken by Robert while interviewing Martin (in Clip 01 it is approximately 60:40. This ratio changed at other times during the the interview).

- The number of questions we inferred Robert asked himself (40 during our interview with him).

- The number of times Robert used the metaphor “fit” (20 during our interview with him).

You can see that we picked out a few ‘extreme’ behaviours to quantify. We did this to find out if our intuitions were based on solid evidence. We were surprised to find out that in all three examples our intuitive count underestimated the frequency of occurrence.

A key element in constructing a model involves detecting patterns. Without access to sophisticated computer software this will need to be some form of qualitative analysis. We used a number of mental filters to repeatedly comb through the text of our interview with Robert. For example we highlighted all the metaphors Robert used. We also distinguished between different kinds of information: external and internal behaviour; outcomes and activities; actual examples and abstractions; perceptual perspectives; organisational levels; the relationship between verbal and non-verbal metaphors; etc. In the Appendix, Section 12 we show a summary of our qualitative analysis which provides a stepping stone from the transcript to our final model.

Another question or frame we were always considering was: How is what is being said and done in the moment a fractal of a more general process? More specifically, how could Robert’s self-modelling be an example of how he models others?

If you review the words we selected to go in our diagrams you will see we favoured Robert’s embodied metaphors (e.g. activating energy, connect to center, marked inside, guided by a feeling, capture the fit, fill in, explore a direction, install in myself, etc.). We did this for a number of reasons: because Robert used so many; because his body was so obviously involved in his modelling; because he said his “somatic mind” was important; but mostly because embodied metaphors are an excellent way for an acquirer to get a sense of how to do someone else’s internal process (see our article Embodied Schema: The basis of embodied cognition).

Once we had identified the key metaphors and noted the sequence of mental processes, we enacted them in the same places in our body and perceptual space, and in the same order as Robert – and noticed our responses. When something didn’t work – we couldn’t go from one behaviour to the next, or there was a clash/inconsistency, or something didn’t fit, or there was an unnecessary piece, or we couldn’t get out of a loop, or whatever – we would adjust the combination and sequence of metaphors. Our aim was to stay close to Robert’s description while searching for the minimal number of elements in the minimal number of steps that would produce the required result – selecting what is essential.

Our method involved lots of trial and feedback. Initially the feedback came from our own reactions as we tried on Robert’s processes and from our joint system as we discussed what we were discovering about our prototype model. Once we had settled on a reasonably robust model we asked individual colleagues to try it out and eventually we invited a group to be our guinea pigs. Their feedback was incorporated into our model and thus we passed through another iteration.

What's still to be done?

In reviewing our model we realise the are a number of gaps. There are three ways we could fill in, firm up and refine the model: a second interview with Robert; a detailed analysis of the videos of Robert modelling Martin; or observe Robert modelling another exemplar.

It wasn’t until after the interview that we realised fitting parts together is itself a selection process, but at a higher logical level than the original selection of parts. Because we were focussed on ‘selecting what is essential’ we didn’t pay as much attention to the processes of ‘fitting’ as we could have. Hence our model of Phase II is a little thin. Although we have some ideas about how Robert noticed parts that fit together and how these are subsequently fitted together into an imagined picture, then into an imagined movie, and finally into physical representation of the model, we would like to get more examples of the different kind of fits, and then look for patterns of similarity and difference at each level of fit.

Also, we have little idea what Robert does with anomalies: those parts that have been selected for significance but that don’t seem to fit anywhere (assuming this happens). Robert gave a clue when he described the testing of things that activated his radar: “Are they still significant? Do they feel resonant? Sometimes they feel more resonant.” From this we guess that things that don’t fit lose their (relative) significance. Somehow they are ‘un-marked’ and disappear from the bag of selected parts, or perhaps they drop out of the picture.

There are plenty of other areas we could investigate, for example how Robert “explores a direction” when he has got a fit. Also we noted that Robert said “If I go out of the center, then there’s all kinds of feelings you can have and you can get lost in feelings.” A useful side area to model would be what first lets him know he has gone, or is going out of his center; and having gone out, how does he get back?

The least complete part of our model is Phase IV. There is another whole modelling project to be done to find out how Robert takes his internally constructed movie and turns it into a physical representation, a model, that can be acquired by someone else. How does he do that?

These are interesting questions that will have to wait for another day. As will a forth iteration. We sense it is possible to refine our model into an even more compact form, but for the time being we like it the way it is.

Symbolic Modelling as a product modelling methodology

Symbolic Modelling emerged out of our modelling of one of the most innovative therapists of our time, David Grove. Our original aim was to generalise David’s approach so it could be used in contexts in addition to individual therapy. It wasn’t until we were well into the project that we had two light-bulb moments: David was continuously modelling his clients – but in a way we had never seen before; and that his process could be coded as a modelling methodology in its own right.

Below we highlight four features of Symbolic Modelling – metaphor, Clean Language, modelling systemically and outcome orientation – which make it suitable as a product modelling methodology, particularly if your outcome is to capture the internal experience of your exemplar.

The role of metaphor

Metaphor is central to Symbolic Modelling. The expanding fields of Embodied Cognition and Cognitive Linguistics are demonstrating that metaphor is fundamental to how we think, feel and act (see George Lakoff and others’ research into metaphor and embodiment).

Throughout this report we have shown how noticing an exemplar’s metaphors helps us to ‘get’ – both cognitively and somatically – the way they do things. This applies not only to explicit metaphors (like: tool, radar, movie) and analogies (Mozart), but also to the many more implicit metaphors such as those highlighted in the Appendix, Section 12. Metaphor enables us to acquire an embodied sense of the interior perspective and internal activities undertaken by an exemplar.

Noticing metaphors is only the first step. Next we consider the logic inherent in these symbolic expressions. Then we wonder how they work together to automatically produce the exemplar’s behaviour. One way we do this is to muse on the presumed entailments of the metaphors and what that tells us about the nature of the exemplar’s way of doing things. For example, we pointed out some of the entailments of Robert’s radar metaphor in our comments on Clip 03. When we considered the metaphors of radar, guided, direction and explore together a theme emerged which suggested a systemic process: detection results in a direction which is explored, leading to further detection and so on.

Noticing metaphors, considering their inherent logic, conceiving a model based on these metaphors, and checking it’s relevance happens throughout the modelling process.

Clean Language

The beating heart of Symbolic Modelling is Clean Language. We believe questions based on David Grove’s clean approach are modelling questions par excellence because they:

- Are short, simple and use the exemplar’s exact words

- Ask for information about ‘what is’; they don’t disagree, deny or negate an exemplar’s experience in any way

- Keep the modeller close to the exemplar’s information – their words, their nonverbals and their perspective

- Keep the modeller’s intrusions into what is being modelled to a minimum

Direct the exemplar’s attention where it needs to be – their interior world.

In short they get the modeller out of the way and encourage an exemplar to self-model.

‘Pure’ Clean Language questions were designed as part of David Grove’s therapeutic process and they do not contain any reference to the therapist. However, since product modelling is not a therapeutic process you will notice that while we keep to the spirit of the principle, at times we relax this criteria somewhat.

We have found that being constrained by the discipline of Clean Language is a way to develop your capacity to model. In becoming proficient at Clean Language you learn to: pay exquisite attention to what the exemplar says and does; utilise their exact descriptions in your questions; let the logic of the exemplar’s information guide your exploration; hold more and more of their process in mind; and become attuned to the idiosyncrasies of their experience.

The video clips and transcript show how we used Clean Language to interview Robert Dilts. In the Appendix, Section 11 we provide a list of the questions we asked. We have removed our repetition of Robert’s words and our few side comments to make it easier for you to see the structure of the questions and how they demonstrate the features listed above.

Modelling systemically

We think humans can be considered to be complex adaptive systems. Therefore it seems congruent to use a systemic, bottom-up perspective to model them.

From a systemic perspective, when we consider how a person consistently performs a complex behaviour we are seeking to identify ‘circular chains of causation’ rather than linear strategies. These will involve escalating and dampening feedback loops which form ‘operational closure’ (see our article, Feedback Loops). That is, these processes have enough internal autonomy to run themselves despite changing circumstances. One example is an ability that is flexible enough to achieve consistent results in a variety of new situations. In Robert’s case, to be able to select what is essential from a wide range of exemplars he has never met before.

Rather than attempting to fit what the exemplar says into predetermined categories or existing models, bottom-up modelling means we let a structure emerge out of the information itself (see our article What is Emergence?). This requires a great deal of trust that the deep structure will become evident, and the result can be somet

Outcome orientation

Maintaining an outcome orientation is vital to a modeller who does not want to get lost in the mass of information presented by an exemplar — much of which will not be relevant. The conundrum is how to work systemically with an emergent process (bottom-up) and have a predetermined desired outcome (top-down). We do this by making our desired outcome for modelling ‘a dynamic reference point’ for everything we do and for every question we ask. In this way a desired outcome is more of a signpost than a destination, and the actual outcome — what is happening moment by moment — provides the pathway. It grounds the process in sensory evidence.

Within our overall outcome for modelling we aim to identify the fundamental pieces of the exemplar’s process and then figure out how they work together as a whole. We call these outcomes within outcomes ‘vectors’ since they determine the direction of our questions over time periods of a few minutes (see our article Vectoring and Systemic Outcome Orientation).

In essence, a systemic outcome orientation enables us to direct our clean questions to areas in the exemplar’s metaphor landscape where something new is likely to emerge. Then we hold their attention in those places long enough for them to find out more about what they do so excellently.

Concluding remarks

We hope you have enjoyed and learned from our wheels-within-wheels presentation of this material. Our aim has been to present the results of our modelling of Robert Dilts and to demonstrate that Symbolic Modelling is a valuable addition to the modelling methodologies already in use.

We would like to emphasise that a model’s usefulness is independent of how it was produced. You can make use of our model of Robert and ignore Symbolic Modelling; or you can adopt a Symbolic Modelling approach without taking on board Robert’s method for selecting – or you can use both.

Having acquired the product of our modelling – selecting what is essential – we can see how it can be applied in many areas. We recommend you try it on and notice whether the feedback you get from the world suggests you now have more choice and greater flexibility to pick out and utilise the ‘signal from the noise’.

Over the years the Symbolic Modelling process has proved fruitful in teasing out ways in which people do things excellently. It is beginning to be applied in academic research as a method to investigate phenomenological information. It has also been used to model the written word in the form of transcripts of client sessions, business meetings, questionnaires, organisational announcements and market research. And these applications haven’t even scratched the surface of what is possible.

There is much to be learned from comparing, contrasting and combining the different modelling methodologies. And as we said at the beginning, they all have their place depending on the context, your outcome and who will be the acquirers.

Once again, our thanks go to Robert Dilts, Martin Snoddon, Fran Burgess and Derek Jackson whose commitment to making modelling more prominent made it possible for us to offer you this report.

The source material in the six appendices referred to in this report are available at Appendix to modelling Robert Dilts modelling.