Presented at The Developing Group, 4 Sep 2010

Contents

2. Cleaning up a questionnaire: ‘Yale University Learning & Development Inventory’

3. Modelling a first-person description: ‘The Shy Person’

4. Modelling a research interview: ‘Work-Life Balance’

5. Modelling a meeting: ‘Food & Drug Advisory Committee’

1. Background

Our interest in this topic goes back to our early work with David Grove where he taught us to “parse” and “muse” on sentences. The verb ‘to parse’ is defined as “to analyse (a sentence) into its parts and describe their syntactic roles”.

David would have a client write a sentence on a flip chart and the training group under his guidance would aim, as he put it, to discern the “intelligence between the lines” i.e. to make explicit what is implicit in the logic of the client’s words (and later, the way they had written those words, which he called Hieroglyphics). As we saw it, his parsing and musing was a way of deconstructing the sentence and constructing a model of the organization of the client’s model of the world.

We described how we parsed, mused on and constructed a model of single sentences in our articles ‘The Emergence of Background Knowledge‘ (1998) and ‘A Model of Musing: The Message in a Metaphor’ (2002). From single sentences we worked our way up to complete client-therapist transcripts.

Since then we have extended the modelling process to advise on company change announcements (Did the announcement send the intended message to the employees?); an Food and Drug Administration meeting (Was the Chair equitable and careful his questions were answered?); an analysis of clinical drug-trial directors (How could best-practice be assessed?); a questionnaire for the Yale University Child Development Study; and academic research on work-life balance to name but a few.

Purpose

Our aim in this paper is to document the value of modelling the written word with a clean and metaphor perspective. To do this we:

- Summerise the kinds of texts that we have modelled

- Provide examples of how we modelled these texts

- Some general guidelines for others to use.

Kinds of written word we have modelled

Single Statement/questions

The articles mentioned above show how we modelled the following client statements:

Questionnaires

Letter to staff

We were asked to comment on an important ‘position statement’ from senior management to their staff. We were asked, if from staff viewpoint the letter was congruence with previous pronouncements and the companies espoused values – it wasn’t.

Transcripts of 1:1 therapy/coaching

We have modelled and annotated over a hundred transcripts of client sessions – often as part of therapist and coach supervision.

Examples of our modelling of our own client sessions can be seen at:

An annotated transcript of a full session about Acceptance.

The session on our DVD, A Strange and Strong Sensation, is accompanied by a 36-page booklet with a full transcript and unique three-perspective explanatory annotation.

See also the three annotated transcripts at the back of Metaphors in Mind.

And James’ short blog, Analysing Transcripts – the 3-paned window method

Exemplar Modelling

We have provided an extensive report of our Modelling of Robert Dilts Modelling which includes our modelling of the transcript of the interview.

First-person accounts

See later in this paper for a step-by-step guide to our modelling of ‘The Shy Person’ from The Guardian.

Academic Research

- To explore how Clean Language could generate insights into the experience of individual participants, and into understandings of the nature of work-life balance generally, through its capacity for eliciting participant-generated (autogenic) metaphors.

- To test the application of Clean Language as a research methodology.

Download report from: WLB_final_report_October_2010.pdf

Download the paper Paul Tosey presented at the 12th International Conference on HRD Research and Practice across Europe, University of Gloucestershire, 25th–27th May 2011: http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/7135/

See later in this paper for an extract from an interview with a manager and our model of their Work-Life Balance process.

Meetings

Process/Technique

Modelling Shared Reality

Further reading

Visit cleanlanguage.com/category/md/ for a number of articles on modelling.

2. Cleaning up a questionnaire

Parts:

B: How we modelled ‘The Learning and Development Inventory’

C: A summary of criteria used to suggest improvements to the LDI

A: The Learning and Development Inventory (LDI) questionnaire

Researchers at The Yale University Child Study Center produced The Learning and Development Inventory (LDI), a questionnaire containing 125 items to be administered to thousands of high school students in the USA. The aim of the questionnaire was to study the relationship between academic success and personal and social development. See: impactanalysis.org/products_ldi.htm

We were invited to review the questionnaire and offer suggestions for improvement from a clean/NLP perspective. Below is an extract from the LDI. It shows the introduction telling the student how to complete the survey and eight statements we have selected which cover a range of criteria we used to suggest improvements.

To improve the quality of the results obtained by the questionnaire we modelled what students would likely have to do internally to make sense of each statement and how that might influence their answer. We then:

- Proposed a ‘cleaner’ wording for each statement. One which gave the student more freedom to answer from their own experience rather than to be constrained or primed by the statement. (While aiming to preserve what appears to be the purpose of each statement.)

- Gave a brief explanation of our reasoning for each of our suggestions.

- Summarised the criteria we had used to evaluate clean-ness and to suggest improvements.

Below is an extract from the High School LDI with 8 sample questions

The purpose of this survey is to understand how students like you experience their high school years. This is a survey, not a test. There are no right or wrong answers. Please be as honest as you can be. We promise not to share your individual answers with anyone. Please tell us how strongly you agree or disagree with each statement by filling in one of the five responses:

Scale:

Strongly-Disagree Disagree Not-Sure Agree Strongly-Agree

1. When I see or hear or feel something that confuses me, I think about it until I can make sense out of it.

2. If another student makes me angry, I am able to put my anger aside after a short time.

3. I write in my day planner all the small steps that I have to take over time in order to accomplish a far-away goal.

4. When another young person is being made fun of in a humiliating way, I join in the laughter.

5. In just about every class, my teachers are making sure that I want to really think about what is being taught

6. Whenever I am working on a project or assignment, I review my work frequently to see if I can find a way to do it better.

7. When I am having personal problems because of something going on at school, I find an adult—either in school or outside school—and I ask for help.

8. I don’t like writing papers/essays, because I have a hard time coming up with ideas to write about.

B: Our Modelling produced suggested improvements

1. Original:

We suggest:

Our explanation:

- Simplified by removing the specific means of being confused “I see or hear or feel”.

- Simplified by removing the metaphor “out”.

2. Original:

We suggest:

Our explanation:

- The suggested formulation does not presuppose that another student can “make” them angry.

- Is the intention to find out whether they think they “am able to” or whether they actually do something to reduce their anger? If the student thinks “I am able – I just don’t” how should they answer?

- ‘Let go’ of anger is an alternative and possibly a more common metaphor than “put aside”.

3. Original:

We suggest:

Our explanation:

- “all” and “small” limits the scope and requires an extra evaluation.

- “have to” is often associated with obligation, whereas “need to” is more a requirement.

- “Over time” is presupposed by “small steps” and “far-away” and is therefore unnecessary.

- “far-away” is a clear spatial metaphor while ‘future’ or perhaps ‘long-term’ is more general. These would make sense both to people who have “far-away” goals and those who don’t.

- Is the question about achieving the outcome, or the process of achieving the outcome?

4. Original:

We suggest:

Our explanation:

- The modifier “young” limits the context. Does it matter whether the person is “young” or not?

5. Original:

We suggest:

Our explanation:

- “most” is simpler to compute than “just about every”

- Our formulation removes the presupposition that teachers are “making sure” that students “want” to think about what is being taught. We think it is sufficient for teachers to ‘encourage’ students to do the act of thinking about what is being taught. This leaves the responsibility for what the student “wants” with them, and the behaviour of ‘encouraging’ with the teacher.

6. Original:

We suggest:

Our explanation:

- “Whenever” means it always happens. If they only review it most of the time should they “agree” or “disagree”?

- How often is “frequently”? If they only need to review their work once or twice, do they “agree” or “disagree”?

- “I am working on a project or assignment” specifies two particular contexts. If the answer is limited to these, what about other types of work? We think the statement is simpler and more direct without this introduction.

- Replaces “find a way to do it better” since it is presupposed in “improve it”.

When I am having personal problems because of something going on at school, I find an adult — either in school or outside school—and I ask for help.

We suggest:

If I have problems because of something going on at school, I ask an adult — either in school or outside school — for help.

Our explanation:

- “When” presupposes they have had (or will have) “personal problems” whereas “if’ leaves it open.

- “I am having” more likely associates the reader into the ongoing experience of personal problems compared to “I have”.

- “Personal” limits the kind of “problems” they can consider. What one person considers personal could be completely different to someone else. Whereas “problems” on its own leaves the reader free to choose the kind of problem that they want to answer about. It depends on the purpose for the statement: Is it more interested in the personal aspect or the ‘asking an adult for help’ aspect? Our suggestion assumes the latter.

- The statement is ambiguous, how should a student to answer the following?:

-I have personal problems at school and I ask an adult for help. – I have personal problems at school and I don’t ask an adult for help. – I have problems at school but they are not personal and I ask an adult for help. – I have problems at school but they are not personal and I don’t ask an adult for help. – I don’t have personal problems because of something going on at school.

Simpler to just say ‘ask an adult for help’ since this presupposes they “find” and adult.

8. Original:

We suggest:

or

Our explanation:

- Is the question trying to find out if students like writing papers/essays or whether they have a hard time coming up with ideas? By having both in the sentence you will not know which their answer applies to.

- It may also bias the answer to “disagree” as you have given them two chances to disagree. Of course you’ve also given them two chances to “agree” but we suspect that the ‘away-from’ reaction might override the ‘towards’ response.

- “Because” specifies this particular reason for not writing papers and essays, and there might be plenty of other reasons.

- If the student agrees with one half and not they other they may well experience a form of ‘cognitive dissonance’ which may affect their state which in turn may influence their answers to subsequent questions.

C. A summary of criteria used to suggest improvements to the LDI

Aim to preserve the meaning/purpose of the original question/statement.

Clarify purpose:

What part do you want the reader to most attend to?

Minimise students’ cognitive load:

- Use simple vocabulary.

- Use simple sentence construction.

- Arrange the sentence in the sequence that the events happen.

- Minimise ambiguity.

- Minimise number of things the reader has to agree/disagree with (ideally one).

- Maximise comprehension for the greatest range of people.

Keep it simple:

- Use as few words as possible (remove unnecessary words).

- Only ask one question – do not ask multi-part questions.=

- Do not duplicate information that is already presupposed.

Maximise scope:

- Do not restrict by specifying the means of something happening.

- Do not restrict with unnecessary modifiers.

- Do not specify the context unless this is precisely what you want.

- Minimise use of explanations, e.g. “because”.

- Maximise applications – unless want answer to be in a specific context.

Use generic metaphors rather than specific metaphors.

Agency

- Don’t use metaphors that presuppose events/people cause internal reactions

- Do not refer to internal motivations. Use behaviours instead.

- Ensure responsibility is with the right agent.

Avoid pre-defining experience

- Do not presuppose the reader has had a particular experience.

- Avoid associating reader into an un-resourceful state.

- Minimise implied judgements.

Minimise universals

- Do not use universals of:

- time “whenever”

space “everywhere”

scale “just about every”

persons “everyone”

3. Modelling a first-person description

Parts:

B: How we modelled ‘The shy person’

C: A model for modelling first-person descriptions

Part A: "What I'm really thinking: The shy person"

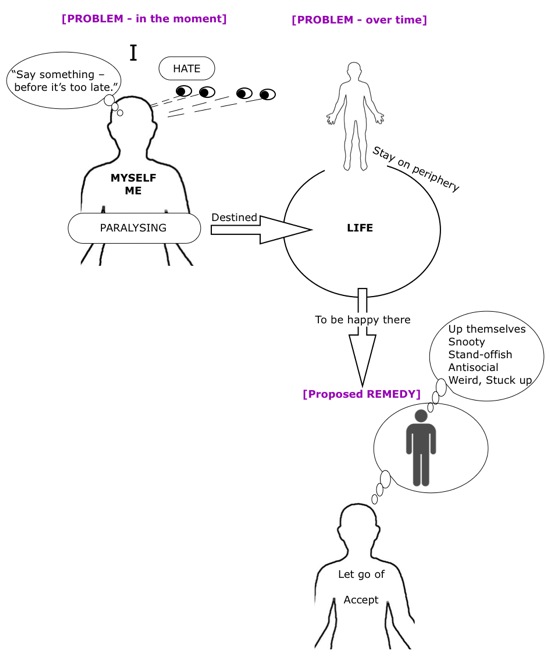

I’m usually thinking, “Say something – before it’s too late!” And then another moment passes and I hate myself a little bit more. I used to think being shy was something I’d grow out of, but it seems that isn’t true. I’ve realised over the years that shy people are perceived as, variously, up themselves, snooty, standoffish, antisocial and weird. You’d think that would be all the motivation I would need to change, but it doesn’t appear to work that way.

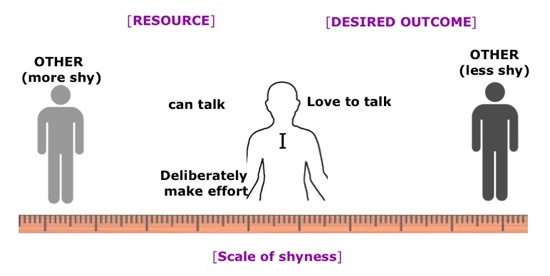

It seems strange to me that people don’t naturally assume that a quiet person is shy or unconfident, rather than arrogant. Strangely, if someone’s even more shy than me, I can talk to them. I find shyness easy to identify in other people, and I will deliberately make an effort with them. It takes one to know one, I suppose.

Even the few people who are my friends say that I was difficult to get to know. Thank goodness they persevered with me. The fear of talking to people is literally paralysing. I hate having more than one pair of eyes on me. My wedding day was traumatic – of course I was happy, but there were just too many people there. I guess I’m destined to stay on the periphery of life.

It’s not a bad place to be, but to be happy there you have to let go of other people’s perceptions of you. For me, that means accepting that there are plenty of people who think I’m stuck up. I’m not. I’d love to talk to you, but you’ll never know that.

Part B: How we modelled 'The shy person'

STAGE 1: PREPARATION

Our desired outcome: To create a model of the internal process of a shy person from their written first-person account:

STAGE 2: INFORMATION GATHERING

2.1 Highlight the metaphors

Below we’ve laid out the text sentence by sentence. Even something as simple as this gives a different perspective and begins to break the tyranny of the narrative. It helps us to look at the text more through process than content eyes.

We went through the text highlighting both the implicit metaphors and the more obvious ones spotted on the first pass. This required us to put on our filtering-for-metaphors hat and ignore everything else:

I’m usually thinking, “Say something – before it’s too late!” And then another moment passes and I hate myself a little bit more. I used to think being shy was something I’d grow out of, but it seems that isn’t true. I’ve realised over the years that shy people are perceived as, variously, up themselves, snooty, standoffish, antisocial and weird. You’d think that would be all the motivation I would need to change, but it doesn’t appear to work that way.

It seems strange to me that people don’t naturally assume that a quiet person is shy or unconfident, rather than arrogant. Strangely, if someone’s even more shy than me, I can talk to them. I find shyness easy to identify in other people, and I will deliberately make an effort with them. It takes one to know one, I suppose.

Even the few people who are my friends say that I was difficult to get to know. Thank goodness they persevered with me. The fear of talking to people is literally paralysing. I hate having more than one pair of eyes on me. My wedding day was traumatic – of course I was happy, but there were just too many people there. I guess I’m destined to stay on the periphery of life.

It’s not a bad place to be, but to be happy there you have to let go of other people’s perceptions of you. For me, that means accepting that there are plenty of people who think I’m stuck up. I’m not. I’d love to talk to you, but you’ll never know that.

Just considering the metaphor begins to give us a sense of the key relationships involved in this person’s constructs.

2.2 Selecting suitable content

Below we have laid out the text sentence by sentence. Even something as simple as this gives a different perspective and begins to break the tyranny of the narrative. It helps us to look at the text through more through process than content eyes.

Next we highlighted text that we considered salient to our desired outcome. Given that we were modelling a mind-body state of ‘shyness’, at this stage we concentrated on identifying internal process. In the table below we comment line-by-line on our selection of what we considered salient or not:

| TRANSCRIPT | IN? | REASONING | |

| 1. | I’m usually thinking, “Say something – before it’s too late!” | √ | Internal dialogue. |

| 2. | And then another moment passes and I hate myself a little bit more. | √ | More internal process and sequence. |

| 3. | I used to think being shy was something I’d grow out of, but it seems that isn’t true. | X | Historical and something that didn’t happen. |

| 4. | I’ve realised over the years that shy people are perceived as, variously, up themselves, snooty, standoffish, antisocial and weird. | √ | Perception of what others think. |

| 5. | You’d think that would be all the motivation I would need to change, but it doesn’t appear to work that way. | X | Something that’s doesn’t have an influence. |

| 6. | It seems strange to me that people don’t naturally assume that a quiet person is shy or unconfident, rather than arrogant. | X | Perception of what others don’t think, and repetition of #4. |

| 7. | Strangely, if someone’s even more shy than me, I can talk to them. | √ | Context where can talk. |

| 8. | I find shyness easy to identify in other people, and I will deliberately make an effort with them. | √ | Skill/Resource |

| 9. | It takes one to know one, I suppose. | X | Presupposed by #8, no new info. |

| 10. | Even the few people who are my friends say that I was difficult to get to know. | X | Presupposed by #4, and about others. |

| 11. | Thank goodness they persevered with me. | X | No new info. |

| 12. | The fear of talking to people is literally paralysing. | √ | Internal process and embodied metaphor. |

| 13. | I hate having more than one pair of eyes on me. | √ | Internal process and embodied metaphor. |

| 14. | My wedding day was traumatic – of course I was happy, but there were just too many people there. | X | Presupposed by #13, no new info. |

| 15. | I guess I’m destined to stay on the periphery of life. | √ | Life belief and embodied metaphor. |

| 16. | It’s not a bad place to be, but to be happy there you have to let go of other people’s perceptions of you. | √ | More about #15 and an implied Remedy. |

| 17. | For me, that means accepting that there are plenty of people who think I’m stuck up. I’m not. | √ | More about the implied Remedy. |

| 18. | I’d love to talk to you, but you’ll never know that. | √ | Desired outcome. |

Interestingly a third of the sentences relate to other people’s thoughts. This indicates how much a part ‘mind-reading’ plays in this person’s way of doing shyness.

2.3 Removing unsuitable content

When we removed the content which did not help us construct a model we were left with about 50% of the words (137 out of 264).

| 1. | I’m usually thinking, “Say something – before it’s too late!” |

| 2. | And then another moment passes and I hate myself a little bit more. |

| 4. | shy people are perceived as, variously, up themselves, snooty, standoffish, antisocial and weird. |

| 7. | if someone’s even more shy than me, I can talk to them. |

| 8. | I find shyness easy to identify in other people, and I will deliberately make an effort with them. |

| 12. | The fear of talking to people is literally paralysing. |

| 13. | I hate having more than one pair of eyes on me. |

| 15. | I’m destined to stay on the periphery of life. |

| 16a. | It’s not a bad place to be, |

| 16b. | but to be happy there you have to let go of other people’s perceptions of you. |

| 17. | that means accepting that there are plenty of people who think I’m stuck up. |

| 18. | I’d love to talk to you |

STAGE 3: MODEL CONSTRUCTION

3.1 Organise the information

Next we grouped the text by kind of information. We used a number of fundamental and inter-related distinctions. Whether something:

- has happened in the past; is still current; or could happen in the future

- happens externally and could be seen, heard or felt by others; or internally and is private

- is considered a Problem; a proposed Remedy; or a desired Outcome (see our PRO model).

Note: these distinctions are from the exemplar’s perspective. For example, if the text indicates that the exemplar considers something is problematic, it’s a problem, whether or not we consider it a problem. It is irrelevant whether people actually consider shy people to be “up themselves, snooty, standoffish, antisocial, weird, arrogant”. The exemplar thinks it, and that will influence how they feel and behave.

2. And then another moment passes and I hate myself a little bit more.

12. The fear of talking to people is literally paralysing.

13. I hate having more than one pair of eyes on me.

16a. It’s not a bad place to be,

16b. but to be happy there you have to let go of other people’s perceptions of you,

4. shy people are perceived as, variously, up themselves, snooty, standoffish, antisocial and weird.

17. For me, that means accepting that there are plenty of people who think I’m stuck up.

8. I find shyness easy to identify in other people, and I will deliberately make an effort with them.

We designated “destined to stay on the periphery of life” as a ‘problem’ even though the person regards it as “not a bad place to be”. This is because the value in them staying on the periphery will likely:

and

As an aside: from a therapeutic point of view this is important since the person will likely consider that not staying on the periphery (and doing the behaviour of not-shy) to be a worse place, and a disincentive to change. Chances are they will need to find a way of keeping whatever the periphery gives them even when they are somewhere else.

3.2 A diagrammatic model of the internal process of ‘The Shy Person’

Part C: A model of how to model the written word

1. PREPARATION

1.1 Read whole thing through.

1.2 Identify desired outcome for modelling and fix in mind.

2. INFORMATION GATHERING

2.1 Highlight metaphors

Since they tell you what it is like on the inside for the person – take their metaphors as a literal description.

2.2 Identify suitable content — that which indicates process information

2.3 Set aside unsuitable content

Explanations

What they don’t do / what isn’t true / what doesn’t work

Examples / stories (unless they give new process information)

3. MODEL CONSTRUCTION

3.1 Group together similar kinds of information

Use as fundamental distinctions as possible. (It is like spreading out all the pieces of a jigsaw before putting similar pieces together.)

3.2 Look for a pattern within each group and identify suitable names for them.

3.3 Diagram out each group using only the exemplar’s words

Use exemplar’s logic to identify Sequential, Causal, Contingent relationships within each group. (These are unlikely to be the same as the order in which the information was presented.)

Allow the structures of your model to emerge from the metaphors, presupposition in language and inherent logic.

Don’t spend too long on any one group, keep iterating around the groups, i.e. keep moving on and coming back to anything that doesn’t make sense or fit together.

3.4 Fit the chunks together

Hold off from combining the groups until you get a sense of the organisation of the background — the nature of the way the person does it. (It is like getting a sense of the picture of the jigsaw when you do not have the lid of the box.)

Use exemplar’s logic to identify Sequential, Causal and Contingent relationships between groups.

Again, keep visiting the various features of the model rather spending too long attempting to figure out one section.

Remove redundant bits.

Continue until it all fits together. (Or you identify ‘outliers’ that don’t seem to fit – they indicate more modelling might be required.)

4. MODEL TESTING

Run the model through your own (and someone else’s) system a few times checking for the four E’s and the three C’s:

Effectiveness

Efficiency

Elegance

Ethics

Completeness

– It is ‘full’

– It answers ‘what else?’ questions with … “nothing “.

Coherency

– It answers ‘why?’ questions from within its own logic.

Consistency

– It is robust, it ‘stands firm’ against challenges

– It can answer ‘what if?’ questions.

Consider how other models might support, enhance or contradict your model.

5. ACQUISITION

Simplify and adjust the model to be congruent with the purpose to which it is going to be applied.

4. Modelling a Research Interview

Parts:

B: Our model of ‘Work-Life Balance’

A: A managers description of Work-Life Balance

The following has been extracted and edited from a verbatim transcript of a 1-hour recorded interview with a manager on the topic of ‘work-life balance’ that formed part of a joint research project undertaken by the Clean Change Company and the University of Surrey in 2010.

When work-life balance is at it’s best that’s like what?

And then what happens?

You’re trying to be a professional and yet you’re juggling so many balls and you know you‘re not doing a very good job juggling them.

And how many balls are you juggling?

It can feel like lots and they probably feel heavier than they might be. As your stress levels go up the balls feel heavier, even though they might not be and you perhaps don’t look at them. It feels like there are more of them and you’re out of control and you haven’t got time to weigh the balls even to work out which ball’s more important than the other and which ones to drop because you’re so pressured. You have to prioritise and focus so you may need to drop a few and concentrate on the really important ones and when you’re stressed it’s difficult to do that.

And as stress levels go up, and balls are heavier then what happens?

You have to throw them faster don’t you?

And what kind of balls are those balls when they get heavier?

When they’re heavy they’re like boulders rather than like tennis balls. Sometimes life feels like going up a mountain and you’re having to dodge boulders coming down. Sometimes you’ve got more boulders you need to dodge and sometimes they’re bigger. And depending on where your balance is at, whether you’re dodging them, depends how well you’re getting up the mountain.

And then what happens?

You keep going up the mountain, you’re managing to dodge the boulders, and you’re making good progress and that must be the ultimate, the balance, but you’re not at the top. You would think that when it’s going well you’re on top of the mountain and looking down. It’s interesting though because you could in theory have a good work/life balance but arguably not be completely stressed out or not feeling time pressure and that for me would be dire. It’s all such a fine balance to find isn’t it because you want a good work/life balance but you also want to be stressed. The idea of not being stressed just sounds awful to me as well!

And is there anything else about that fine balance?

Yes, and so I am getting up the mountain and you’ve got a strong desire to just keep- keep going and not give up and the day when you say in your work, ‘Oh I’m giving up now’ – that’s the time to leave the company and go somewhere else or do something else where you want to improve.

And is there a relationship between getting up the mountain, boulders coming down and stress levels?

Definitely yes. The more boulders that are coming down, the bigger they are, the more stressed you are trying to dodge them and you might not be able to – you’re probably going to get crushed at the bottom ultimately!

And then what happens?

You take yourself away from the mountain to a fresh environment. You take yourself away from all the daily sort of stresses and strains and you’re in a new environment and you can relax and just switch off.

B: Our model of the manager's WLB

5. Modelling a Meeting - The Food & Drug Advisory (FDA) Committee

Below you can download:

A 23-page “Report of a Pilot to Explore the Use of Information Modelling of FDA Advisory Committee Transcripts as a Tool for Optimizing Messages at Future Meetings”.

Prepared by Louise Oram and James Lawley of 9CQ Limited, 2 August 2004

In total 59 people participated in the two-day meeting. The verbatim transcript of the meeting ran to 737 pages!

Summary of Results

The Food and Drug Advisory Committee meeting of 26 and 27 February 2004 included presentations by the FDA, Hoffmann La-Roche and Generic firms. Our analysis shows that Information Modelling can provide information outside that normally available to personnel preparing for an FDA Advisory Committee meeting. In particular 9CQ established that:

Over 50% of questions asked of the Sponsors were not answered or were only partially answered. This suggests inadequate preparation both in terms of content and being able to respond to the wide variety of ways Committee members format their questions. Very often these were complex, disguised or ambiguous, and sometimes attempted to lead or restrict the answer.

The Hoffmann La-Roche representative apparently antagonized FDA staff, and repeatedly misunderstood or did not address questions put by Committee members. Also, an unconscious language pattern of his may have had a detrimental affect on how his presentation and answers were received.

We could find little evidence that Sponsors utilized individual linguistic preferences and styles when replying to Committee members. They therefore missed opportunities to build rapport and credibility.

The Committee Chair’s personal views seriously impeded his ability to remain unbiased in his chairing of the meeting. Added to that, it wasn’t until 90% of the meeting had taken place that the FDA revealed certain options they had asked the Committee to consider were “not an acceptable course of action.” These incidents may have endangered the integrity of the whole Advisory Committee process.

Poor chairing meant that some member’s suggestions were lost, pivotal scientific data from a Generic firm was ignored, and there was often confusion over what was being discussed at any moment.

Our analysis identified who said the most and who said the least. While certain Committee members, voting Consultants and FDA staff made many more contributions than others, the Chair dominated the meeting. Excluding pure chairing activities, he made five times as many contributions as any other Committee member.

Detailed analysis with verbatim examples are given in the full report which you can download original report (PDF)