Background

When we were modelling David Grove in the mid 1990s he made use of a model which he referred to as “The observer, the observed and the relationship between”. He was making use of the age-old notion that in order to be able to conceptualise how we see, feel, hear, taste, smell, think, intuit, etc. something, we consider the ‘something’ as separate from our ‘self’. But, we cannot be entirely separate because to have any awareness of the something, we have to relate to it in some way. ‘Relate’ in this sense is a very broad term. It covers anything that connects or links us to the something. At the most basic level if two things are separate then they will have a spatial relationship. Equally, if we know something exists we must have a way of knowing or a means-of-perceiving relationship with it.

In the 1980s, during his Child Within phase, David Grove borrowed the Gestalt Psychology distinction of ‘figure and ground’ to refer to a metaphor and the environment of the metaphor, e.g. the ‘figure’ might be a child, trapped in the ‘ground’ of a bedroom. David tracked whether the client was attending to the child or the bedroom and would direct his questions to the relevant place.

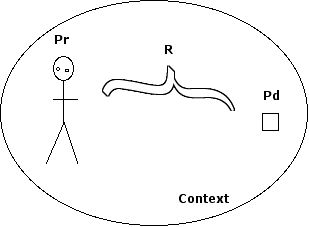

The two models (Observer-Relationship-Observed and Figure/Ground) are related because the ‘figure’ and the ‘observed’ refer to the same aspect of perception — what the client is attending to. We realised that these two models could be combined and generalised. For example we considered that the ‘observer’ and ‘observed’ metaphors presupposed a visual modality and might undervalue other ways of perceiving. Hence we adopted more general terms: ‘perceiver’ and ‘perceived’. This had the added advantage of signalling that we are in the domain of perceptions, not reality. Secondly, we considered the metaphor of ‘ground’ was likely to imply the physical environment, so we plumped for the more abstract ‘context’. Hence we arrived at our PPRC model (see diagram 1).>1

Diagram 1: Perceiver, Perceived, Relationship between, in a Context.2

So far we have been concentrating on perceptual models, but if you believe (as we do) that language both reflects and influences perception, then it is hardly surprising that linguists have their own version, i.e. sentences are composed of: Subject, Object and Verb.3

Points to Note

The key to using the PPRC model is to realise that it is a model of perception from the client’s perspective. By inference you can use a client’s verbal and nonverbal behaviour to construct a model of the way they have constructed their model of their world. It will not be the same as their model but it should be isomorphic (have a similar structure) to their model.

Being able to distinguish between the four PPRC components is not an exact science because it depends on how you ‘punctuate’ perception (as Gregory Bateson would say). It’s always possible to deconstruct a sentence into PPRC categories in a number of ways. Your aim is to discern how the client is punctuating their world.

Because the PPRC model is from the client’s perspective it enables the facilitator to make sense of the client’s descriptions and hence ask questions which make sense to the client (even if they can’t answer them!). Using this model is what we call ‘bottom-down’ modelling. It is ‘down’ because it deconstructs a whole sentence into parts. However the categories have such wide acceptance and stay relatively close to the client’s experience that we consider them to be toward the ‘bottom’ end of the abstraction hierarchy (in contrast to, say, our Problem Remedy Outcome model, or Eric Berne’s Parent Adult Child which are increasingly towards the top).

The client’s perception is dynamic and this model takes a snapshot of the client’s process of perceiving. No part of a client’s perception is a perceiver or is a perceived, etc. But at that nanosecond, it can be useful to deconstruct the whole perception into these four ‘functions’. A fraction of a second later a perceived can become a perceiver, the ground can become the figure, etc. However if you take a number of snapshots of a client’s way of perceiving, a pattern emerges which usually has remarkable stability.

PPRC is one way to conceptualise how it is possible to have a ‘sense of self’ or ‘self-awareness’ or to be ‘self-conscious’. By making whatever we consider to be our ‘self’ the perceived, we create a meta perspective. This, of course, raises the age-old question: ‘But then, who is the thinker of this thought?’.

PPRC is only a model, it’s not applicable to everyone in every situation. For example, it doesn’t seem to correlate with those situations where we ‘lose our self’ in a book, or in a similarly engaging activity. However as soon as we attempt to describe that experience we are probably back to using PPRC. Another area the model doesn’t seem to apply is in the domain of mystical states. The description given by mystics, regardless of their spiritual tradition suggests that the mystical experience involves the collapsing, synthesising or merging of at least two, if not all four of the PPRC, e.g. “feeling at one with [a perceived]”, “merging with nature”, “seeing the world in a grain of sand”, “losing a sense of being separate”, etc.

Advantages of using the PPRC model

It is a model of perception (i.e. “the structure of subjective experience”). It is not an interpretative or explanatory model. It is not trying to describe ‘why’ or ‘how’; it is more about describing ‘what’. It works with what is presented and doesn’t require the deduction of missing pieces or extrapolation outside of the data (although this can be useful to consider afterwards).

Although your model is typically constructed from a facilitator’s perspective, its purpose is to represent the client’s perspective. Even a simple statement like “I want food” presupposes some meta-awareness of an ‘I’ that wants, and therefore whoever or whatever is making the statement is more than, or beyond, the ‘I’ describing the want. This is one of the principles of Roberto Assagioli’s Psychosynthesis and the Buddhist traditions — that there is ‘pure consciousness’ beyond ego.

It allows for multiple perceivers — simultaneous and sequential.

It removes the dichotomy between ‘association’ and ‘dissociation’. In the PPRC model the perceiver is always ‘associated’ in some way, i.e. perceiving by some means from some place — it just might not be associated into their physical body.

It removes the stigma of ‘dissociation’. Dissociation becomes a particular kind of configuration of the model (of which we are all capable to some extent) rather than a ‘disorder’. (Of course if a client habitually uses one configuration there will be serious consequences in their life — but that’s true for any configuration.)

It removes the need for a person to be ‘integrated’. Instead it recognises that certain configurations may be better adapted to certain circumstances. Dustin Hoffman has said that he had to learn how to keep a part of himself separate from the role he was acting — his gesture indicated that this aspect of his ‘self’ was about a foot above and a few inches behind his head.

It follows the structure of language. We assume that because of the similarities across languages they arose out of a common structure of experience. Because of this PPRC makes intuitive sense and doesn’t require the learning of categories. (Having said that, since ‘context’ is always in the background it is a slippery concept to get hold of.)

PPRC is highly flexible because any of the functions can change to become one of the other functions. For instance, a perceiver, a relationship or a context automatically becomes the perceived as soon as the client attends to one of them.

Recognising the component functions of PPRC

The four functions of PPRC can be identified through any of the three key forms of behaviour:

Language

Vocal qualities

Movement of the body

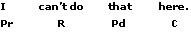

Structurally, most simple sentences can be deconstructed into PPRC thus:

However when we take into account the speaker’s tonal emphasis (indicated by underline), our model of what they are attending to can change:4

To repeat, these are our way of applying the PPRC model to this sentence. You might punctuate it differently. The proof of the model’s value is in how it influences your interventions, and how these are received by the client — not just in any one interaction, but over a session and a series of sessions.

Using nonverbal behaviour to identify the components of PPRC usually requires observing a difference in behaviour. Differences in behaviour are either:

Sequential

Simultaneous.

Examples of sequential differences in behaviour are:

When a client’s voice drops to a whisper, goes up a register and takes on childlike qualities this may indicate a change of perceiver.

A change in a line of sight might indicate a change to what is perceived.

Changes in the pattern of gestures could signal a change of context.

Simultaneous differences occur when, for example, multiple perceivers are indicated. When what someone says indicates one perceiver while what they do indicates another, e.g. saying “I agree” while shaking their head; or looking up and saying “he’s trapped down there”.5

Using PPRC to recognise changes in the pattern of perception

Nasrudin sat on a river bank when someone shouted to him from the opposite side: “Hey! how do I get across?” – “You are across!” Nasrudin shouted back.6

Although clients’ perceptions are dynamic they change within limits that have a continuity for the client, i.e. they change to stay the same. However, when a client says “I’ve changed” or “Things seem different now” or “I can see it in a different light” they are telling us that they are experiencing a discontinuity — a configuration of PPRC that is unfamiliar to them.

A shift in any one of the four functions of PPRC can produce a change, although usually any significant change in one will have an knock-on effect to at least one of the others, e.g.

The perceived changes and so does the perceiver’s relationship with it: a scary brown bear becomes a cuddly teddy bear.

A perceived moves from outside to inside the client’s body and the perceiver changes: a lost essence returns home to fill an empty heart and the client has a solid sense of self as a result.

When the pattern of relationships between the four functions changes (i.e. there is a change to the ‘pattern of organisation’), a higher (second)-order change has occurred. Then the client doesn’t just change a perception, they change their way of perceiving. This typically adds a whole layer of choice.

We speculate that it may be possible to classify the significance of a change by (a) how many of the four functions change, and (b) how much of the rest of the client’s system is affected.

Emergent Knowledge

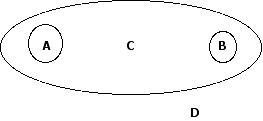

Since the development of Clean Space and Emergent Knowledge processes, David has been using a spatial variation of the above models which he labels:

Space of A, the client (or more accurately, a perceiver that wants/doesn’t want B)

Space of B, the mission/problem statement or drawing.

Space between, C

Space around/outside, D

Diagram 2: Space of A; space of B; the space between, C; and the space outside, D.7

The parallels between the Emergent Knowledge model and PPRC are plain to see.

© 2006, Penny Tompkins and James Lawley

References

1 Metaphors in Mind, James Lawley and Penny Tompkins (2000) pages 122-128 and other references in the index to ‘perceiver’, ‘relationship’ and ‘context’.

2 We were also influenced by John McWhirter’s FROM-TO-IN model, see ‘Re-Modelling NLP, Parts 1-14‘, Rapport, issues 43-59 (1998-2003).

3 Phil Swallow and Corrie van Wijk have been engaged in a fascinating discussion about the similarities and differences between these models

on the Clean Forum: www.cleanforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=136

4 This is a modification of an activity we saw Ian McDermott demonstrate in 1991 to illustrate how changes in emphasis can indicate different Neuro-Logical Levels as defined by Robert Dilts, see nlpuniversitypress.com/html2/N32.html

5 Richard Bandler and John Grinder labelled indications of multiple perceivers as “simultaneous and sequential incongruity” however that’s a facilitator’s perspective. Being able to take multiple perspectives is not necessarily incongruous. For example, one of the most congruent statements I’ve [James] ever heard was from a man who said “I’ve spent my whole life searching for certainty, and now I’ve learned to act with doubt.” Acting with doubt may seem incongruent to an observer.

6 An example of a perceiver-perceived switch, supplied by Phil Swallow.

7 Six Degrees of Freedom: Intuitive problem solving with emergent Knowledge by David Grove with Carol Wilson, ReSource, fifth edition, Summer 2005.

First presented to The Developing Group, 4 February, 2006.