Presented at The Developing Group 24 May 2014

Leader, leading, leadership. Follower, following, but not follower-ship; why not?

The metaphor of ‘leader’ and ‘follower’ is so embedded in our culture and language that we tend to forget there are other ways to think about and describe the relationship. For a start, leaders have no role without followers. Yet how often is the role of the follower considered? “And when you are following at your best, that’s like what?”

Once you look at the leader-follower dynamic systemically it starts to look less clear-cut, and just as with a couple dancing, it’s often hard to know who is leading whom. In different contexts, and at different moments, leaders become followers and vice versa.

Interestingly much of nature operates quite successfully without an overt-leader: fish shoal, insects swarm, antelopes herd, and whole ecosystems thrive for millions of years without a leader. The lack of a leader in an antifragile1 self-organising system warrants a re-think of our models of leadership.

In this paper we explore the systemic nature of the leader–follower dynamic from a clean perspective. Not necessarily when either role is overt, but rather those subtle, often undervalued aspects of leading and following that we all engage in from time to time.

“You cannot examine one end of a relationship and make any sense.

What you make is a disaster.”

Gregory Bateson

How you manage to lead

Twenty years ago we wrote an article ‘How You Manage to Lead’.2 In that article, Penny tells a story of when she co-ran a company manufacturing oil-field equipment. The story isn’t about one of the people in a leadership role, but about George, an unassuming worker who simply did what he thought was right and unwittingly demonstrated inspiring leadership.

Looking back, the article was an early attempt to extend thinking about leaders to beyond the classic – and in our experience limited – categories embedded in hierarchical organisational structures.

These notes revisit that quest twenty years on. We don’t have any more answers than we did then, but we sure have a whole lot more questions!

Who leads and who follows?

Who is the leader in the film Arthur? Dudley Moore the rich employer who is a drunken playboy or Sir John Gielgud the straight-talking servant?

The Beverly Hills Supper Club fire in Kentucky on the night of May 28, 1977 was the third deadliest nightclub fire in U.S. history. A total of 165 persons died and over 200 were injured. In The Unthinkable: When Disaster Strikes, Amanda Ripley reports on a sociological investigation which examined the hundreds of police interviews taken soon after the fire. The research “estimated 60 per cent of employees [who had received no emergency training] tried to help in some way – either by directing guests to safety or fighting the fire. By comparison, only 17 percent of guests helped.” (pp. 113-115).

Not only did the guests not help each other, many of them did not even help themselves. One employee was trying to escape when he stumbled upon about a hundred guests in a room filling with smoke. There was total silence and no one was moving. (Were they each following each other’s inaction?) The employee simply said to one guest “follow me” and led them all to safety.

No doubt the guests, dressed in ball gowns and tuxedoes, were “well-to-do” and could have been regarded as leaders in other contexts such as their businesses and families – and yet in this crisis they became passive. The waiters, bar staff and cooks took the lead saving hundreds of lives in the process.

Where do the metaphors ‘lead’ and ‘follow’ come from?

‘Lead’, like almost every other metaphor, is based on its physical source:

To show (someone or something) the way to a destination by going in front of or beside them; To cause (a person or animal) to go with one by holding them by the hand, a halter, a rope, etc., while moving forward.

By metaphorical extension lead has come to also mean:

- To be in charge or command of; To organize and direct.

- To be the most advanced or successful in a particular area.

- To be be a reason or motive for (someone), especially to set (a process) in motion or to culminate in (a particular event): The inspiring speech led him to sign up.

Correspondingly, ‘follow’ has its roots in:

To go or come after (a person or thing proceeding ahead); to move or travel behind; to go along or in the same direction as or parallel to (a route or path).

Which by metaphorical extension has come to also mean:

- To come after in time or order; to happen after (something else) as a consequence.

- To act according to (an instruction or precept): he is following written instructions.

- To conform to: the film faithfully follows Shakespeare’s plot.

- To act according to the example of (someone): he follows Aristotle in believing this.

- To treat as a teacher or guide: those who seek to follow Jesus Christ.

- To strive after; aim at: I follow fame.

“He who thinks he leads, but has no followers, is only taking a walk.” Anon.

Interestingly, both ‘lead’ and ‘follow’ derive from old German words closely related to the physical meaning. The physical basis of the metaphor presupposes that both words involve a relationship; since you can’t have a leader without a follower.

Systemically speaking, leaders (whether they want to or not) are being influenced by their followers. When this happens, who is leading whom? Celebrities talk of being held captive by their fans’ perception of them. Some speak of becoming caricatures of their public presence. Many political leaders have failed to navigate between the sirens of populism and the rocks of autonomous thought.

The film, The Life of Brian magnificently lampoons the leader-follower relationship. Brian, the reluctant leader manages to escape the crowd following him but while running away he looses his shoe. One of the leaders of the following crowd holds up the shoe Brian lost and exhorts: “The shoe is the sign. Let us follow His example.” An argument ensues about what the sign means and then a woman holds up a gourd and shouts, “Follow the gourd”. The crowd eventually head off splitting into two camps, those that follow the shoe and those that follow the gourd.3

While there may be some culturally iconic images of a leader, Heather Cairns-Lee’s PhD research using Clean Language suggests that the naturally occurring metaphors of leaders are more idiosyncratic than previously thought. Heather also examines the implicit theories held by leaders and the implications that result from them becoming more aware of their inner mental models.4

Leadership and morality

With all the hype around “developing leaders” it’s easy to forget leadership is neutral. It is not inherently a good thing. There can be ‘effective’ leaders who do ‘bad’ things and ‘ineffective’ leaders who do ‘good’ things, and vice versa in both cases. Leadership and morality are independent.

| Effective leaders who do good | Effective leaders who do bad |

| Ineffective leaders who do good | Ineffective leaders who do bad |

Do the same four categories hold for “followers”? Absolutely. Think of the many examples like the American soldiers who loyally followed Lieutenant Calley and massacred a whole village of Vietnamese civilians. Then there are the Edward Snowden’s of this world who refuse to follow orders. And what about the thousands of Civil Rights marchers who make up the crowd? Are they followers or leaders?

People who will not follow a leader can either be considered ‘obstructors’, or less judgmentally as ‘preservers’. Often, in seeking to hold out against change they are aiming to conserve what exists. This is a vital function in any system that is going to demonstrate longevity. Are they ‘good’ or ‘bad’ followers? It all depends who is judging, when and against what criteria.

Skin in the game

Nassim Nicholas Taleb says leaders without “skin in the game” have nothing to lose and are inevitably tempted to put their own interests before their followers or the bigger purpose. Unless the ever-present possibility of corruption is acknowledged and steps taken to “ward it off”, the longer a leader leads, the more likely they will succumb. Harry Belafonte and Stanley Levison, at the funeral of their friend Martin Luther King Jr. described how he handled political temptation (he was apparently less successful at handling a more physical kind of temptation):

He drained his closest friends for advice; he searched within himself for answers; he prayed intensely for guidance. He suspected himself of corruption continually, to ward it off. None of his detractors, and there were many, could be as ruthless in questioning his motives or his judgment as he was to himself. (p. 347, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr., Coretta Scott King, 1969)

Beyond dualism

Of course, leader-follower is a dualism. This is easy to see when we apply the concept of leadership to our self. We have to split ourself into leader and led: I don’t allow myself to be happy. I self-sabotage. I couldn’t stop myself. I followed my intuition.

Are some people neither leading nor following – at least some of the time? And if so, what are they doing? Are some people both following and leading? Derek Sivers shows an interesting video and asks about the “first follower”. Is it effective followship or “an underestimated form of leadership”?5

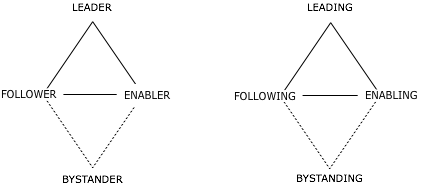

We suggest there are at least two other functions or roles involved. We’ll call them ‘supporting / enabling’ and ‘bystanding’. A diagram of these four roles and corresponding behaviours is below:6

Part of the role of mentors, advocates, coaches and sponsors is to support leaders to lead and followers to follow – without necessarily being led or following themselves.

Also, some people stand on the sidelines, or opt out. Or at least they appear to. People choose not to vote in elections. Captains of sinking ferries have been known to be the first to leave the ship. However, systemically, all behaviour influences. Bystanding will have an effect but it is a different effect from leading, following or enabling. As this chilling poem by Pastor Martin Neimoller suggests, it can be disastrous:

In Germany, they first came for the communists,

and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a communist.

Then they came for the jews,

and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a jew.

Then they came for the trade unionists,

and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a trade unionist.

Then they came for the homosexuals, and I didn’t speak up

because I wasn’t a homosexual.

Then they came for the catholics, and I didn’t speak up

because I was a protestant.

Then they came for me –

but by that time there was no one left to speak up.

Leaderless self-organising systems

In an article on emergence we said: “When we see repeated structure emerging out of apparent chaos, our first impulse is to build a centralized model to explain that behavior. It’s as if we can’t help looking for nonexistent ‘decision-makers’, ‘controllers’ or ‘pacemakers’ [cells that order the behavior of other cells]”.7

It may be a common human impulse to look for someone or something creating the directionality that systems display, but there is now overwhelming evidence that many self-organising systems exist perfectly well without a leader. And as hard as it is to accept, the same may be true for the dynamic emergent self-organising system we know best – ourself.

Added to that we now know that in human systems, people who are at two and three degrees of separation have an influence, even if there is no direct contact:

Using data from the renowned Framingham Heart Study which started in 1948 with 5,209 adults in Framingham, Massachusetts, and is now on its third generation of participants, Christakis and Fowler indicate that everything we do or say tends to ripple through our network, having an impact on our friends (one degree), our friends’ friends (two degrees), and our friends’ friends’ friends (three degrees). Fowler and Christakis have found that if a person is happy, the likelihood that a close friend will also be happy is increased by 15%. At two degrees of separation, this likelihood is increased by 10%, and at three degrees of separation, this increase of probability falls to 6% but the effect is still significant.8

Is our state, our thoughts and our actions being led by hundreds of people we have never met? To some degree it would appear so. Then this would mean we are all leaders and we are all followers at one and the same time!

Notes

1 See the slides of James’ presentation to the Clean Conference 2013, Antifragility, Black Swans and Befriending Uncertainty.

2 Tompkins, P. & Lawley, J. (1995) How You Manage To Lead, Rapport, 27.

3 See video clip: The Shoe Is The Sign

4 Cairns-Lee, H. (2013). The Inner World of Leaders, Why Metaphors for Leadership Matter, Developing Leaders, Executive Education in Practice, Issue 13, Oct 2013 pp. 27-33, IEDP. Download original article.

5 Derek Sivers. How to start a movement. TED2010.

6 Is there is a parallel with the Karpman Drama Triangle used in Transactional Analysis? A person (or group) can adopt any of the roles at any moment and people can move around the triangle. When someone moves, others have to react – and that usually involves them moving too.

7 Penny Tompkins & James Lawley (2002). What is Emergence?

8 Timothy T.C. (2009). The Three Degrees of Influence and Happiness.