Published in Rapport, 57, Autumn 2002

The Metaphor and Clean Language Research Group suggests there is more to perceiving than meets the eye.

Perceiving is something I do all the time and until recently I hadn’t thought twice about it. Then I spent a day considering perceiving and its implications for facilitators and their clients at our Metaphor and Clean Language Research Group, and this article has developed from that. As a doctor who worked in general practice I was only too aware of the difficulties of communication where doctor and patient each had their own way of perceiving.

A facilitator using ‘Clean Language’ as originated by David Grove is for the most part working with the client’s perceptions. The facilitator refers almost exclusively to these in the context of the client’s outcome. I find that using Clean Language in a clinical setting to discover the client’s perceptions can take a little longer than the traditional way but is invaluable, over time, in helping me provide for the particular needs of each individual. It is also safer to consider the client’s unique experience from the perspective of their own perceptions. It reduces the problems of transference and helps reduce misunderstandings. My own ideas and beliefs about client meaning remain with me, and my interference with the client’s self-generated healing process is minimised.

NLP (Neuro-Linguistic Programming) suggests that if you don’t like the world as you perceive it, you can change your perception. A facilitator, therapist or coach can help a person perceive differently. A facilitator using Clean Language ensures that the client is exploring their own process without bias from the facilitator’s.

“In reality, each reader reads only what is already within himself. The book is only a kind of optical instrument which the writer offers to the reader to enable him to discover in himself what he could not have found but for the aid of the book.” Marcel Proust

I shall suggest a few considerations that facilitators of all kinds may like to keep in mind as I consider perceivers from four perspectives:

- How perceivers experience a perception for themselves.

- When perceivers are communicating with others.

- The act of perceiving in different ways.

- Perceivers in the therapy setting.

1. How perceivers experience a perception for themselves.

A question to bear in mind is:

Is the client using a wider range of their attributes?

Perceptions include their perceivers. People perceive and, whenever they do, their attributes influence what they perceive at any given time. These attributes are both archetypal and individual. Archetypal attributes are the prototypes and the original models of our societies that we hold in common. Some archetypal attributes:

parent/ child/ adult

demon/ maiden/ wise person

thinking/ feeling

big chunk/ small chunk

Take my perception of a cat as an example of how an individual can be influenced by archetypal attributes. As a child, I perceive a soft, lively, interesting cat. The attributes of an archetypal child which influence the child’s perception are being playful and explorative, and this results in my perceiving a soft, lively interesting cat. An archetypal adult’sattributes involved in perceiving a cat are being playful, explorative and responsible for the cat’s well being. Thus as an adult I perceive a soft, lively, interesting cat that needs regular feeding, litter trays and visits to the vet.

Individual attributes might include particular likes and dislikes and different energy levels. One of the individual attributes that affects my perceptions is my liking for chocolate. Seeing, smelling or tasting chocolate is a pleasurable perception for me. The perception of someone who dislikes chocolate will be different, and for someone who likes chocolate but is forbidden to eat it, the perception will be more complicated!

The process of perceiving may be represented as a constellation of filters we apply to the information we take in. As with attributes, some filters are common to us and others are individual. When information is brought into awareness to create our personal version of ‘reality’, the particular filters we use allow us to choose and select the perceptions we want. In a therapy situation Clean Language helps the therapist remain with the meaning that the client makes of the world. The therapist does not have to guess or speculate about the filters operating for the client.

When I worked in General Practice I used my own filters to assess the patient’s situation, even though the patient perceived the world using quite different filters. Now when I use Clean Language as a counsellor my clients have no need to connect or adjust to my perceptions. I acknowledge the client’s archetypal and individual attributes, and work with the client’s world as perceived through their filters. Since using Clean Language I am confident that my clients achieve their outcomes in fewer sessions.

2. When perceivers are communicating with others

Questions to consider: Where is the client perceiving from, with what filters, and what form is the perception taking?

Where is the client perceiving from?

You might equally ask this question of yourself. NLP recognises three basic perceptual positions:

1st – from the perceiver’s position and perspective,

2nd – from the other person’s, and

3rd – overall to the communication between them.

Body language may sometimes be a clue as to where a person is perceiving from. If this is 2nd or 3rd perceptual position the perceiver, whether therapist or client, may move slightly from the position used for 1st position – they might move their chair back when perceiving from 2nd position or tilt their head up for 3rd position. The different body positions people take for the 3 perceptual positions are likely to be consistent over the course of any one session.

Which filters are involved?

The facilitator may attempt to perceive from the client’s position using their perception of the client’s filters, or from their own position using their own filters.

The intensity and quality of the perception can vary in different perceptual positions depending on the filters operating at that moment. For example, feet perceived by a chiropodist may differ from the perception of feet by a therapist. A chiropodist may see feet that have muscle imbalance with the arch support. A therapist using Symbolic Modelling may see the alignment of the same feet as a pointer to the location of a symbol in the client’s metaphor landscape.

The particular words and phrases we use affect communication because of the filters we have in use. NLP and Ericksonian teachings show different ways that words may impact on perception. A marketing manager may describe a project in terms of ‘battling on’, ‘against the odds’, and ‘winning a victory over competitors’. The works manager might perceive the project through filters that are more to do with ‘team sharing’ and ‘pooling resources for all to benefit’.

Filters and consciousness

Some perceptions are subliminal; filtered out of conscious perception and accepted by unconscious perception. Nonverbal communication is often subliminal. Hence the quality and quantity of our communication will vary between our use of email, answer machine, telephone and face-to-face methods.

When perceivers are physically close they can use all forms of perception, and there is the potential for rich and varied communication. Conscious and unconscious filters can limit perception, however. The clothes a person wears can affect the result of a job interview – a clearer exchange of information might be possible if the funky outfit isn’t seen!

Filters and physical, mental and spiritual states.

When I am healthy and newly in love I perceive a different world from the world that exists for me in bed with ‘flu.

People with multiple personality disorder or manic depression perceive very different internal and external worlds at different times.

Cultural norms are filters. In Western cultures, perceptual positions are coded grammatically – “I am, you are, he is” – whereas in some African cultures people tend to use the more encompassing “we”, which becomes a whole village’s rather than one person’s perception. Western perceivers may perceive from the head rather than the heart or the gut, because academically-oriented, cognitive-based achievement has traditionally been the norm in paternalistic Western systems.

What forms does the perception take?

Our perception may have the form of visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, olfactory or gustatory representations, or any combination of these. Communicating our perception may be via language, music, visual art or touch. The form itself will contribute to, and potentially limit, the perception and the communication. A client perceiving or communicating in one kind of form may get new information if invited to perceive or communicate in another.

If a client is helped to identify the forms of their perceptions, and the perceptual positions from which they perceive these forms, they can consider an experience both in its parts and in its entirety. In a therapy session the client may describe an argument with their partner when there were raised voices, gesturing hands, and feelings of fright and despair. Clean Language can be utilized to explore any of these forms.

3. The act of perceiving in different ways.

Question: Is “it” there, not there or somewhere in between?

We have multiple simultaneous perceptions and select from these to perceive the world at any moment in time. The selection is partly unconscious and partly conscious. We can decide what we wish to concentrate on at a given moment. If I am facilitating a client, I am directing my attention to the individual and their outcome. If the fire alarm goes off, my perception of the situation changes.

We perceive ourselves as having a place in the universe with a role, an intention, at a certain time, and all of these in turn affect our perceiving.

I can imagine a perception in vision, in sound or in bodily feeling. Take the situation where I strike a match to light the gas. I can imagine what might happen if I drop the lighted match into a bin of waste paper, so I decide to blow out the match first.

Some agoraphobic clients restrict their lives severely with imagined perceptions, such as being trapped underground in a tube train. They may perceive

For example, they may perceive the inside of the tube train and themselves sitting on a seat (“what is there”). They may also perceive the possibility of an explosion in the station that would block their exit from the underground system (“what is not there”). And they may perceive feelings such as a fear that they will not complete the journey safely in the usual manner (“the part in between”). A therapist can help an agoraphobic client explore their perceptions in the safety of the therapy room by leading them through the actual, the imagined and the part in between.

Question: Is a time element involved?

Incorporating time is another way of perceiving. We can perceive multiple things simultaneously, sequentially, or with grades of fuzziness in between. I arrive at a workshop and perceive, simultaneously, groups of people, a table of books, an array of chairs and the registration area. To continue effectively I must then perceive these things sequentially. Some clients may be overwhelmed by simultaneous perception and find it useful for the therapist to direct their attention to a more sequential way of perceiving.

4. Perceivers in the therapy setting

Question: Is there a physical, mental, spiritual or logical level change?

Communicating our perceptions in the therapy setting usually involves speech, but may also make use of writing, sound, diagrams and pictures. Each medium has its limits and constraints. With each there is a spectrum of attention, for facilitator and the client, that can be represented in various ways:

one/ many

single/ multiple

whole/ part

central/ peripheral

broad/ narrow

diffuse/ concentrated

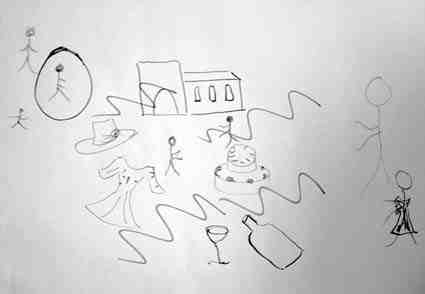

The facilitator can direct the client’s attention to a way of perceiving that may be less familiar to the client. The expectation would be that new information appears. Take a client who wants to cope better with organising a wedding. They describe the issue as central and frightening and draw a diagram that is shown below.

The therapist can direct the client’s attention to the periphery of this centre, the wider considerations of the problem, perhaps even to the cousin who is between jobs and able to take some of the responsibilities.

Change across the spectrum of attention can be achieved as a result of:

A client with painful or difficult material may achieve their outcome by completely switching attention – for example, from seeing their forthcoming aeroplane flight in full technicolour to seeing it in distant monochrome, or by switching attention from the means to the end. At other times a gentle moving towards or gradual transitioning may be more appropriate.

Appreciation of the NLP logical levels of environment, behaviour, capability, belief, identity, and spiritual can help the therapist perceive the client’s world. Recognising that a client believes that they cannot travel on an aeroplane, the therapist may direct the client’s attention to elaborating this belief in the knowledge that the client is capable of getting on, staying on and getting off the aeroplane.

Conclusion

During a consultation a client may say, “Something has just happened; I see it differently. I haven’t perceived this in this way before. I feel different.” Facilitator and client have worked together and a new perception has emerged. In developing and maturing this change, we might ask ourselves:

Is the client using a wider range of their attributes? (Section 1)

Where am I/where is the client perceiving from, and what form is the perception taking? (Section 2.)

What modifying filters are in use? (Section 2.)

Is “it” there, not there or somewhere in between? (Section 3.)

Is a time element involved? (Section 3.)

Is there a physical, mental, spiritual or logical level change? (Section 4.)

We are perceiving beings from before birth until we die. Modifying perception is central to the interaction of facilitator and client. Many clients find it easier and more effective to modify their perceptions in metaphor rather than cognitively, or from within their familiar unproductive patterns. Symbolic Modelling using Clean Language is a facilitatory model geared specifically to helping clients realise what they want to have happen as perceivers of their own process.