Presented at The Developing Group 1 Dec 2012

The introduction to our chapter in Innovations in NLP says The Clean Community has “a high value of working collaboratively”. At the recent NLP Leadership Summit (London, Nov 2012) Michael Hall and Frank Pucelik posed the question “How do we need to cooperate, even collaborate, as leaders in the field?” Co-incidentally, we have just completed a University of Michigan Coursera course entitled Model Thinking, in which one of the modules included “seven ways to produce cooperation”.

We began to wonder: What does it mean to ‘collaborate’? Is it the same or different as ‘cooperating’? Where does ‘co-inspiring’ fit in? What does a clean approach add to the mix? And how do we do any of them?

The etymology of collaboration and cooperation has much the same meaning: “to work together”. Yet collaborating feels different to cooperating. When we were discussing this with some Dutch friends they instantly said that there was a huge distinction for them. As an example they cited Holland’s occupation by Nazi forces during World War II where collaborating was viewed very different to cooperating. You could cooperate in the interest of your own survival, but if you were seen to collaborate you were considered a traitor.

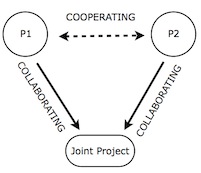

The Collins English Dictionary helps to make the distinction clear. It defines cooperate as a “joint operation or action” or “assistance or willingness to assist”. While collaborate (often followed by on, with, etc.) means “the act of working with another or others on a joint project”.

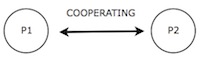

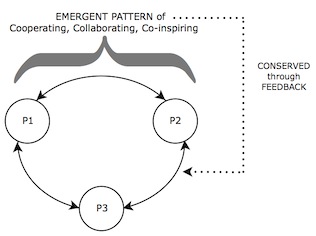

We can cooperate without working on a joint project. I can cooperate by actively assisting you, and I can cooperate by passively agreeing not to obstruct your plans. But if we collaborate we are both actively engaged in working together towards a mutual outcome. Thus, I can cooperate without collaborating, but I cannot collaborate without cooperating. The following schematics should help to give the distinction a form:1

P = Person (or Perceiver)

Solid line = Explicit effect

Dashed line = Implicit effect

Models of cooperation

- Direct Reciprocity – If I scratch your back, you will be more likely to scratch mine.3

- Indirect Reciprocity – If others know I’ve scratched your back, they will be more likely to scratch mine.

- Network Reciprocity – The more my neighbours scratch other people’s backs, the more likely I will also.

- Group Selection – Groups with more cooperators will likely fare better than groups with less and will tend to survive and thrive, increasing cooperators throughout the population.

- Kin Selection – How much I cooperate with you depends on how closely we are related. The closer we are related the more your survival increases the chances that some of my genes get passed on.

- Laws/Prohibitions – It can be in the collective interest to oblige individuals to act cooperatively; requiring vehicle drivers to stop at pedestrian crossings for example.

- Incentives – Rewarding cooperative behaviour (such as Nobel Peace prizes and Good Deed awards) encourages similar behaviour.

Collaboration

Steve Gilligan highlights an important aspect of “generative collaboration” compared to co-dependency:

By carefully joining with another person generative collaboration can occur at a deeper level. This does not mean that people merge together and lose their respective identities; rather, the mutual trance opens a larger field that holds each individual member, plus a deeper systemic intelligence.4

The internet has not only enabled new ways to collaborate on a planetary scale, it has also inspired new ways to think about collaboration. To give just a few examples:

- Open source software development – e.g. Firefox, Linux

- Crowdsourcing – outsourcing tasks to an undefined distributed group of people

- Human-based computation – large numbers of humans and computers working together distributively to solve problems.

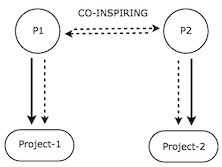

Co-inspiration

As well as cooperation and collaboration there is another way of working together championed by Humberto Matura, which he calls co-inspiration. Our understanding is that co-inspiring happens when two or more people discuss their own projects, interests and reflections in a way that supports each person to gain from the conversation. It is a cooperative endeavour but it is not collaboration because there is no joint project.5

As Maturana puts it:

Co-inspiration is a space of conversation that is sufficiently expanded and long. For it to happen the space must be of sufficient duration for consensuality to have presence, and comprise sufficient domains of interaction to implicate systemic as well as linear logical rationality. It can only happen [with a] fundamental grounding of co-existence in the emotion of love; love for each other and love for mother earth.

In this our orientation of desires may be or become co-incident, and then we are free. Freedom in a group is obtained when there is co-inspiration, otherwise we are in a position of coercion to achieve results. The alternative to co-inspiration is domination or tyranny. In co-inspiration there is no attachment to a particular form of outcome, what is conserved is the orientation.6 (our italics)

Co-inspiring can be diagrammed thus:

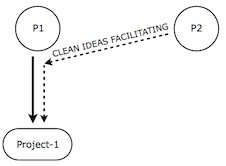

Clean Ideas Facilitating

In 2010 on a Clean Change Company Module 8 (Integration and Application: Applying clean principles out in the world) we introduced another model of working together – clean ideas facilitating. The aim of the clean ideas-facilitator is to set aside their own ‘projects’ and to support another person (or persons) entirely from within the other’s mental model. Although many facilitators will say this is what they already do, without Clean Language and a knowledge of metaphor they cannot not unwittingly introduce their own ideas.

Clean ideas facilitation is similar to clean therapy/coaching, but they are not the same. While personal change may occur, it is not the purpose. Instead the clean ideas facilitator operates ‘on behalf of’ the development of the idea:7

Systemic Perspective

Cooperating, collaborating and co-inspiring are not things that can be done alone – the “co” gives that away. They are, by definition, relational. Rather than regarding them as behaviours, they can be seen as emergent properties of a system of interacting parts where no part can control or determine the output of the system (Bateson). They are related but different emergent patterns that, as Maturana says, are conserved:

A pattern emerges from the network of interactions that together preserve the characterisation of the system as cooperating, collaborating or co-inspiring. The output from the system can then be assessed; for its effectiveness, efficiency, elegance and ethics for example.

Thinking in this way encourages us to consider a different set of questions. What ‘boundary conditions’ (thresholds) indicate the system is moving out of cooperating, collaborating or co-inspiring into something else? What is too little and what is too much that tips the system into a different state?

Co-operating with Self

Because humans are able to split their mind (have multiple simultaneous and sequential perceivers) all of the above applies intra-psychically as well as between people. We might think it would be natural for parts of a person to collaborate; however, since the mind is not subject to the same social and external influences that individuals are, it has the capacity to maintain internal conflicts for a lifetime – or resolve them in an instant.

Notes

1 For more on this kind of schema see Embodied Schema and our PPRC (Perceiver-Perceived-Relationship-Context) model.

2 Martin A. Nowak and Karl Sigmund, ‘How populations cohere: five rules for cooperation’ Chapter 2 in Theoretical Ecology: Principles and Applications, Robert May and Angela R. McLean (Eds. 2007). Download chapter from ResearchGate

3 See Robert Cialdini, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (2007) for more on the effects of reciprocity.

4 Stephen Gilligan, Generative Trance: The Experience of Creative Flow, Crown House, 2012.

5 An example of how we used co-inspiring as the starting point for a group clean space process is at: cleanlanguage.co.uk/articles/articles/255/5/Clean-Space-Revisited/Page5.html

6 Presentation by Humberto Maturana to the American Society for Cybernetics Conference, Santa Cruz, California, April 2, 1998 as recreated by his colleague Pille Bunnell (personal email Nov 29, 2004).

7 For an investigation into the perspective of a clean facilitator see: Pointing to a new modelling perspective.