Do you know what Life is to me? …

[A] play of forces and waves of forces, at the same time one and many …

a sea of forces flowing and rushing together, eternally changing.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Will to Power1

In Metaphors in Mind, Penny Tompkins and I highlight that metaphors of force are the second most frequently used metaphors (after space), “not only in English but in every other language that has been studied” (Steven Pinker, How The Mind Works, 1998, p. 355).

Zoltán Kövecses provides dozens of common expressions which imply a metaphorical force is involved in the way the speaker is making sense of their experience (2002, pp. 19-25). Here are a few of his examples:

She swept me off my feet.

You’re driving me nuts.

Don’t push me!

I was overwhelmed.

He went crazy.

She solved the problem step by step.

Inflation is soaring.

Although the concept of force is crucial to our modelling of clients’ inner worlds, Penny and I have not written about it for many years (see Further Reading). In this paper I explore clients’ subjective sense of the dynamics of force, how it affects behaviour and the role it plays in Symbolic Modelling.

Table of Contents

1. Force

Force is an interesting concept. It always involves an interplay of several elements from which complex relationships emerge. Cognitive Linguistics is the the study of the correspondence between language and mind-body experience. It analyses perceptions of both physical and metaphorical ‘force’ in terms of patterns of force dynamics.

These patterns are embodied and give coherent, meaningful structure to our physical experience at a preconceptual level, though we are eventually taught names for at least some of these patterns (Johnson, 1987, p. 13, italics in original).

From the physical interaction of forces we learn to think in terms of cause-effect. Our meaning-making of physical forces and causation provides a basis for a creative metaphorical extension into the non-physical world of desires motivating action, problems getting in our way and humans influencing each other. The operation of forces is perhaps the primary way metaphorical causation is conceived in language and thought. By the time we reach adulthood we have acquired a system of concepts based on an intuitive ‘folk physics’. This is not the physics of scientists, it’s our everyday perceptions of how the world works, derived from our embodied and cultural experience.

2. Force schema

Mark Johnson suggests (1987, pp. 43-44) that the nature of force commonly involves the generic features listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Generic features of forces

|

These features do not operate independently but as a unified structure, a gestalt, Although we may not be aware of it, we primarily experience patterns of force though our body – the felt sense of movement. Johnson identifies seven of the most common forces (pp. 45-48) to which I’ve added example metaphors in Table 2.

Table 2: Seven common forces with sample metaphors

| Compulsion | She made me do it. |

| Blockage | My relationship failed at the first hurdle. |

| Counterforce | I was just about to do it when I had second thoughts. |

| Diversion | I find his suggestions so distracting. |

| Removal of restraint | I unmasked and showed my true face to the world. |

| Enablement | Now I feel empowered to act. |

| Attraction | That smile is irresistible. |

The essential structure of particular forces can be represented by a schema (a generic image). In Figure 1, I’ve slightly modified Johnson’s schema and added a commentary to the seven common forces listed in Table 2. The solid arrows show the direction of forces ‘A’ and ‘C’, the dotted arrows show the effect of the interaction of these forces or their encounter with a blockage, ‘B’.

3. Force dynamics

Leonard Talmy comes at force-dynamics from a different direction to Johnson. Talmy unpacks the dynamics of force and shows that these patterns are more prevalent in (metaphorical) language than we might think.

Talmy emphasises that “underlying all more complex force-dynamic patterns is the … opposition of two forces” (De Mulder, 2021, p. 229). This dynamic is characterised first by a “force-exerting entity” (an agent), and second by a force that has an opposing effect on the first, for example by friction, resistance or a barrier. Similarly, desires can be opposed by a command, by morals or by social pressure. Sometimes the first force exceeds the second, sometimes it’s the other way round, and sometimes they balance each other equally resulting a steady state.

Talmy notes that the effects created by the dynamics of ‘towards action’ forces interacting with ‘towards rest’ forces involves four outcomes:

1. If a force-exerting entity has a tendency towards action and the opposing force is weaker the result will be action.

2. If a force-exerting entity has a tendency towards action and the opposing force is stronger the result will be rest.

3. If a force-exerting entity has a tendency towards rest and the opposing force is weaker the result will be rest.

4. If a force-exerting entity has a tendency towards rest and the opposing force is stronger the result will be action.

I provide examples of these four combinations below. The italicised words indicate the net effect resulting from the opposing forces:

1. My desire to change will overcome all obstacles.

2. I’m motivated but it’s just too risky.

3. I held my position in the face of criticism.

4. I shifted my attitude as a result of her powerful argument.

Next I describe the distinction Talmy makes between two ways force manifests in language – through conceptual content and conceptual structure.

4. Forces indicated by content

Conceptual content includes most verbs. Since the prototypical verb involves action, and action requires some kind of force, almost all verbs involve a dynamic of forces. For example:

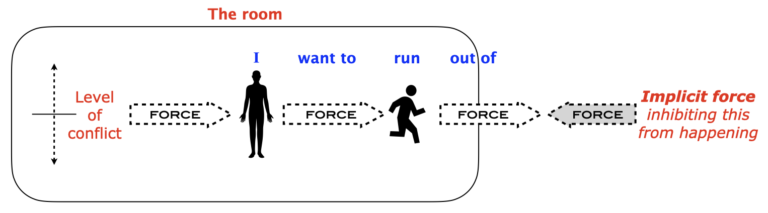

Because of the level of conflict I want to run out of the room.

Whether we take “run” literally or metaphorically it involves a force that initiates the running; a force to keep running until the person is out of the room; after which, presumably, this force is no longer required.

Interestingly, the person’s experience is more complex than this simple analysis suggests. ‘Wants’ and other kinds of desire are usually conceived as motivating behaviour since they ‘move’ us to act. They are therefore often regarded as causes of a force.

But that is not all. The person who made this statement didn’t physically move, and the statement implies they hadn’t (yet) metaphorically left the room either. This suggests that some opposing force operated to inhibit the “want” from being enacted. And this inhibiting force was at least equal to the desire to run.

As well as “run”, a similar kind of modelling can be applied to tens of thousands of action-based verbs that provide the content of a given scene.

5. Forces indicated by structure

In addition to the more overt force dynamics involved in ‘run’ and ‘not-run’, another force is implicit in the sentence, Because of the level of conflict I want to run out of the room. The use of “because” suggests that “the level of conflict” is motivating the desire to run and is therefore likely conceived as some kind of causal force.

My schema of the force dynamics in the above statement is shown in Figure 2:

The schema shows that although the person doesn’t run out of the room, their “want” presumably remains as long as the “level of conflict” persists. And logically, a change in the the “level of conflict” will result in a change in the force-dynamics.

As well as because, examples of other structural concepts that suggest the involvement of opposing forces via an inferential logic are: but, despite, besides, even though, nevertheless, moreover, granted, instead, after all, on the contrary. (De Mulder, 2021, p. 232)

For example, the common configuration in change-work, ‘desired Outcome but Problem’ is often conceived of as the problem preventing the client’s desire from being realised. When this is the case the but implies the problem is an opposing force which counters the desirer’s outcome.

I want to move forward in life but I’m too scared.

A similar logic is involved when a client’s statement is of the form ‘Problem despite Resource’. Here the problem may be construed as a force restricting the resource from being (fully) accessed:

I want to move forward in life but I’m too scared.

6. Forces and embodiment

Mark Johnson reminds us that,

Because force is everywhere, we tend to take it for granted and overlook the nature of its operation. We easily forget that our bodies are a cluster of forces and that every event of which we are a part consists, minimally of forces of interaction (1987, p. 42, italics in original).

In his work with metaphor and Clean Language, David Grove developed a keen sense that the way a person moves their body is intimately linked to how they express their experience. David called the dance between these movements, gesturing for example, and the location or form of a client’s metaphors, “choreography”. As Johnson’s quote suggests, patterns of force-dynamics are not only embedded in language, they are also grounded non-linguistically in the way our body works and how it interacts with the world. In short, Cognitive Linguistics has shown that language and cognition are embodied in multiple ways.

Advertisers are keenly aware of the effect of embodied force-dynamics during the buying process. I remember an interview from decades ago with an advertising executive for a credit card company. He explained that his job was to influence the customer at the moment they opened their wallet and had to choose which credit card to use. His adverts were designed so that at the moment of choice the customer leans towards his company’s card. He went on to say that it only needed to be the slightest impetuous because the customer was in a moment of indecision and even the smallest factor would relieve the uncertainty and influence their decision.

David Grove regularly said “Change takes place in a context”. In Symbolic Modelling, the context we work with is the client’s metaphor landscape, a 4-dimensional “psychescape” (Grove) that symbolises the workings of a client’s mind-body system. When forces are involved in a client’s experience they will be embodied in their metaphors, and their physical body will likely be enacting the force-dynamics. For example, the client may rock back and forth if they are “pulled and pushed”, or sway from side to side if they are “pulled in two directions”, or a foot may twitch when it wants to run but is unable. Enacting these kinds of metaphors nonverbally can involve barely perceptible micro-muscular movements or the unmissable involvement of the client’s whole body, or anything in between.

7. Clean language questions about forces

Any of the 8 most universal Clean Language questions can be asked of a client’s words that indicate a force. Table 3 lists the function of these questions related to force and provides a sample format.

Table 3: Basic Clean Language questions asked of a force

| Function of question | Sample Clean Language question format |

| Elaborate on features of the force | And is there anything else about [Force]? |

| Identify the type of force involved | And what kind of [Force] is that [Force]? |

| Locate the force | And where is [Force]? |

| Identify a metaphor for the force | And that’s [Force] like what? |

| Identify the event preceding the force | And what happens just before [Force]? |

| Identify the event following the force | And when [Force] then what happens? |

| Examine the relationship between forces | And when [Force A] what happens to [Force B]? |

| Identify the intention of a force-exerting agent | And what would [Agent of force] like to have happen? |

Note, the questions above can be asked of verbal as well as nonverbal indicators of force. Also, any of the generic features of force identified by Johnson in Table 1 may prompt a contextually clean question. I provide a few examples of these in Table 4.

Table 4: Generic features of force prompting contextually clean questions

| Client statement | Implied feature of force-dynamics | Contextually clean question |

| 1. My desire to change will overcome all obstacles. | Sequence or chain of causation | And does anything need to happen to overcome all obstacles? |

2. I’m motivated but it’s just too risky. | Origin or source of the force | And where does that too risky come from? |

| 3. I held my position in the face of criticism. | Direction of the force | And from which direction did that criticism come? |

| 4. I shifted my attitude as a result of her powerful argument. | Degree or intensity | And how did you know her argument was powerful? |

There are always a number of Clean Language questions that could be selected; so how do you know which one to ask and what to ask it of? There is no simple answer to this question. However there are some guidelines.

Asking Clean Language questions is an intentional endeavour. In a coaching or therapy session for example, the questions are asked on behalf of the client’s system. Deciding which question to ask is informed by a number of factors, the main ones being: The client’s desired outcome; the inherent logic of their inner world; and their in-the-moment reaction to their inner metaphorical world (which Grove called “psychoactivity“) .

8. Forces in change-work

Force dynamics are highly relevant in change-work because metaphors of opposing forces are commonly expressed by clients who are experiencing a dilemma, a conflict, a long-standing problem, desires that can’t be satisfied, feeling stuck, and so on. These kinds of experiences often have the structure of a bind or a double bind.

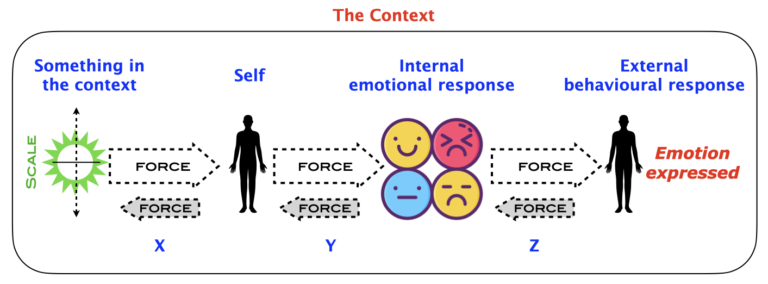

Zoltán Kövecses (2020) has reviewed how we describe our emotions in terms of both force-dynamics and conceptual metaphor theory. He suggests this commonly involves a two-stage process. In the first stage, something in the local environment acts on a person resulting in an emotional response. In the second stage this emotion is the cause of a further response which is expressed internally or externally.

Figure 3 represents my interpretation of Kövecses’ two-stage process for a person having an emotion and expressing it with external behaviour, e.g. They made me get so angry I couldn’t stop myself screaming.

In the example, They made me get so angry I couldn’t stop myself screaming, the force dynamics at ‘X’ is represented by “made”, at ‘Y’ by “get”, and a ‘Z’ by “couldn’t stop”.

Throughout the process shown in Figure 3, Talmy’s opposing forces (represented by the darker left-facing arrows) are weaker than the forces of action. If, however, any of the forces represented by right-facing arrows are met with a greater opposing force there will be a restrained response. The expression of emotions could be inhibited by stronger opposing forces at X, Y or Z as suggested in the following examples:

X. Their criticism just bounced off me.

Y. I felt the intention behind their criticism but I remained calm.

Z. Even though it hurt I refused to respond to their criticism.

There are three additional things to note about Figure 3:

First and most important, these schema represent a common first-person subjective experience as expressed in language and behaviour. These schema are not aiming to be a scientific third-person representation of emotion.

Second, Kövecses (2002, p. 21) points out that given the word ‘emotion’ is derived from ‘to move’, it is unsurprising that most emotions are comprehended via force metaphors. However, force is not significant in every emotional experience. Consider for instance, these metaphors for fear: ’I’m chilled at the thought’, ‘I had cold feet’, and these for love ‘I’m crazy about her’, ‘I was in paradise’. Forces may be involved in the process of the client getting to or accessing these emotional states, but forces are not inherent in the statements.

Third, I have added an icon for scale to the ‘something in the context’ to represent the amount or degree that needs to be present before it has an impact on the person. The scale doesn’t only apply in the moment, it can also represent an accumulation of small things that over time result in an emotional response. A particularly clear example would be a case of coercive control where the micro-aggressions accumulate until the sufferer eventually goes over threshold with a violent outburst.

In Figure 3 the ‘middle’ forces that connect Kövecses’ two stages operate entirely within the person. When this dynamic is the focus of attention the metaphors often indicate that the person construes themself as having two separate persona or parts (the line numbers represent the four combinations discussed in Section 3):

1. I have to work hard to keep my body in shape.

2. A part of me didn’t let me do it.

3. I retained my dignity when usually my emotions get the better of me.

4. Against my better judgement I took a leap into the unknown.

In Symbolic Modelling recognising force dynamics is vital to facilitating a client to self-model the structure and processes of these kind of experiences.

9. Choice points

We have expanded David Grove’s work to include those key moments, choice points, when a person’s system is at a tipping point. At these moments a person can either do a familiar (unwanted) pattern; or they can do something different. At a choice point, the force-dynamics operating on the person – and in particular their body – will commonly be the defining factor that determines which way the system tips. In the above credit card story above, if we substitute choosing a credit card with choosing a beneficial behaviour over an unwanted action, we have a direct analogy for what happens at a choice point.

In Symbolic Modelling we facilitate a client to self-model their metaphors (including the force-dynamics) at the moment of choice. Choice points can pass in the blink of an eye. One of the features of Symbolic Modelling is that it can facilitate the client to ‘stretch time’ so what happens during these fleeting moments can be brought into awareness and attended to for 5, 10 or 15 minutes. This gives the client time to embody and make sense of the dynamics operating in their system.

We have found that it is crucial for a client’s desired outcome to be involved in the forces operating at the tipping-point moment. Once the precise choice point has been identified and the key force-dynamics of the current pattern are in awareness, the client is invited to consider:

And when [client’s metaphor at choice point], what would you like to have happen?

For instance, a Ukrainian living through the trauma of war had a painful dilemma. During the session the client “begins to feel a contact with my body”, which is unusual for her, and she starts to feel a “very unpleasant trembling is coming” which will mean “I lose control over the world”.

The client sums up her dilemma:

I want it [the trembling] to stop and at the same time I don’t want it to stop. Because if it will stop that means my child will die [voice breaks].

Beginning to feel her body tremble signals a choice point for the client’s system. There is a brief moment when the forces acting on the client are equal and opposite. Does she revert to her usual pattern and disconnect from her body, or does she stay with the trembling and lose her sense of control? Neither of which she wants. Our question invites her to remain at this choice point and to consider:

So you want it to stop and at the same time you don’t want it to stop. And so when you want it to stop and don’t want it to stop, what would you like to have happen – when you want both?

At first the client had no answer to this question – a common initial response. However, after a few more questions that invite her to continue to attend to the point of choice, the client said:

[Long pause] Now I see the exit from all of that. It seems that I’m thinking too much. Thinking, thinking, thinking about what will be tomorrow, what will be the day after tomorrow. And if I stop doing this, and if I just live here-and-now, day-by-day, then this will be better and everything will come together.

As you can see, ‘What would you like to have happen?’ is not an abstract question when the client’s body is living and reacting to the forces operating at a choice point in their metaphor landscape. Rather it invites the client to face their personal (painful) current reality and consider how they would like it to be.

A particularly revealing choice point can happen after a client has experienced changes during a session. Occasionally, changes to hold for a few days before a client finds themselves running their previous pattern once again. Change is nonlinear. Two steps forward can be followed by one, two or three steps back. Setbacks provide a perfect opportunity for the client to discover the ‘forces’ operating on them at moment the old pattern recurred. For example, what forces result in them “stepping back”, “taking a turn for the worse” or “relapsing” (a metaphor deriving from the Latin,’to slip back’)?

As a result of considering the ‘What would you like to have happen?’ question at a choice point, clients are more likely to continue to lean towards their desired behaviour. Unlike the credit card advertiser who is aiming to influence other people for the benefit of the company, in Symbolic Modelling, the client learns from themself how to nudge their system into more of the beneficial responses and behaviours they seek.

10. The idiosyncratic takes priority over the generic

The near-universal ways humans conceive and configure their inner world are extremely useful for facilitators. In the early stages of a session they can provide a framework for the facilitator to invite a client to attend to various aspects of their experience. However, and it is a big ‘however’, there are four important things to note.

First, even though the generic model of force-dynamics has wide applicability, there will always be people whose internal world doesn’t involve forces.

Second, even when a metaphor involving forces is present, every client is unique and they may have created an internal world where their force-dynamics operate in an entirely idiosyncratic way.

Third, even when indicated, force-dynamics may not be relevant to, or a significant factor in a client realising their desired outcome.

Fourth, bear in mind that there are always cultural variations to experience. For example, there are a variety of cultural beliefs about what can and cannot be an agent of force.

In Symbolic Modelling, the individual’s unique structure provides the base material for both the client’s self-modelling and the facilitator’s modelling of the client’s metaphor landscape.

This requires the facilitator to hold any generic model lightly, and to be on the lookout for indicators that it may not apply with this client. Whenever this happens, the generic model recedes into the background of the facilitator’s musing to be replaced and foregrounded by the idiosyncratic structure of the client’s experience.

11. A case study

The following is an extract from a Symbolic Modelling client session that clearly involves force-dynamics. I unpack the early stages of the session and provide schema representing the shifting force-dynamics structuring the client’s experience.

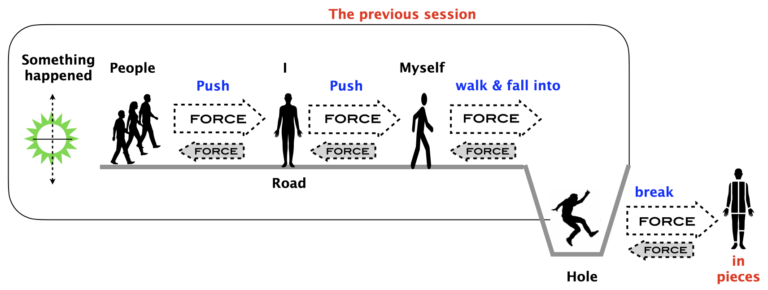

In a previous coaching session (with another coach) the client had “walked into a hole I couldn’t get out of.” This left him feeling “broken in pieces”. The client described how this happened:

It feels like I’m on a road and I’m being pushed by other people who are behind me. And I push myself because they are pushing me … And when I push myself, I walk and fall into the hole.

Looking at these statements through a force-dynamics lens suggests:

The client experienced a force of being “pushed by other people” from “behind”.

This caused another force to “push myself”.

A third force keeps the client walking until he “fall[s] into the hole”.

(I’m ignoring the force of gravity which doesn’t seem salient to the client’s model.)

As a result he feels “broken” which, since it occurred after the session, may be the result of another force.

Given this is not what the client wanted, we can assume that all these forces were stronger than any opposing forces attempting to maintain his unbroken state.

Figure 4 maps the client’s process in the previous session as a schema.

By the time the client came to see me he was no longer in the hole or broken, but was “trying hard not to break apart [again].” This implies:

Since the previous session, a force had gotten him out of the hole, and possibly another force returned him to an unbroken state.

The forces which caused the client to “break apart” had the potential to repeat the process in the current session.

In this moment, the client’s “trying hard” was the opposing force successfully keeping the process from repeating.

Based on these assumptions, Figure 5 shows the force-dynamics at the start of his session wi

When I asked the client what he would like to have happen in this session his first response was:

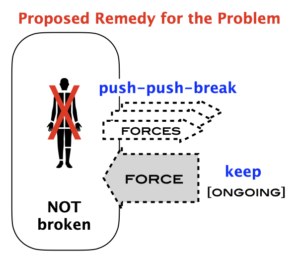

To keep myself from breaking into pieces.

From this I surmised that here needs to be an ongoing force which “keeps” the client from “breaking apart”. If “trying hard” cannot be sustained the other forces will again have a relatively greater strength. This would result in the client repeating the breaking-apart pattern, possibly in the current session.

In terms of the Problem-Remedy-Outcome model, the client is proposing a Remedy to his Problem as shown in Figure 6.

After some thought the client seems to recognise that “trying hard” is a useful short-term Remedy but a longer-term Outcome was needed. He said:

I would like to be aware of the signs before I start breaking apart.

Presumably, when the client is aware of the “signs before I start” he’ll be in a better position to do something other than repeat the walking-into-a-hole-breaking-apart pattern he had enacted “trillions” of times before.

The “signs before I start” represent a choice point. My modelling of the client’s desired outcome is shown in Figure 7.

As the session progresses the client’s metaphor landscape suddenly becomes psychoactive and he reports:

Now, that’s interesting. I’m seeing the hole in front of me now as we continue … I’d like to stay still and collect myself.

Perceptually speaking the client is now exactly where he needs to be, “aware of the signs before I start breaking apart”. As a result he formulates a new desired outcome, “to stay still and collect myself”. The client is quiet and still for the next few minutes. I assume the forces that are enabling him to “stay still’ and to “collect myself” are now strong enough to counter being “pushed” by others or himself.

In this moment the client is doing exactly what he needs to do in situations which have the potential to prompt the breaking-apart pattern. By living in a new metaphor he is making the session a microcosm of his real life.

A fuller report on how the session unfolds is available at cleanlanguage.com/coaching-a-client-who-felt-broken-from-coaching/.

In summary, by symbolically modelling and depicting the force-dynamics organising this client’s experience, I have aimed to show how the logic of a client’s metaphor landscape is revealed to the facilitator. This window into the client’s mind-body knowing enabled me to have a sense of his lived experience from his perspective. This is not ‘empathy’, nor is it ‘building an alliance with the client’, rather it is being in deep rapport with the structure of the client’s patterns. It enables me to choose Clean Language questions that precisely point to particular perceptual times and places in a client’s inner world.

12. In conclusion

The concept of force dynamics offers valuable insights into how individuals make sense of their experience, structure their inner world, and repeat (unwanted) patterns of behaviour.

Cognitive linguists have demonstrated that metaphors of force — such as compulsion, blockage, and counterforce — are not only prevalent in language but also deeply embedded in the embodied experience of individuals. These metaphors emerge when our perceptions of our body’s interactions with physical forces are extended into non-physical domains such as emotions, desires, and interpersonal relationships.

Understanding force dynamics and its embodied nature provides facilitators of Symbolic Modelling and Clean Language with generic schema. These can be used to formulate questions that facilitate clients to recognise crucial moments — choice points in unwanted patterns — where they can self-model the interplay of opposing forces enabling their system to reorientate itself toward a desired outcome.

The case study and examples discussed illustrate that force dynamics are highly individualised, and their relevance to a client’s process depends on how these forces are configured within the context of their metaphor landscape. While generic models of force dynamics offer a helpful framework, it is the individual nuances of each client’s experience that must guide the therapeutic or coaching process.

Ultimately, force dynamics enrich our understanding of how individuals construct their inner worlds, providing a sophisticated method for modelling complex mind-body experiences. By recognising the role of force in shaping emotion, thought and behaviour, and by using Clean Language to inquire into the structure of metaphorical forces, facilitators can support clients to learn new ways to respond to challenges, navigate dilemmas and move towards their preferred future.

13. Notes and Further reading

1 Entry 1067. Quoted in Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter: A political economy of things (2010) p. 54.

2 To emphasise the embodied nature of force-dynamics, Talmy calls these two force-exerting entities: the “agonist” and the opposing “antagonist”. An agonist is a muscle whose contraction moves a part of the body directly. An antagonist is a counteracting muscle.

3 See my chapter, ‘Metaphor, embodiment and tacit learning’ in Becoming a Teacher: The dance between tacit and explicit knowledge, V. Švec, J. Nehyba & P. Svojanovský (eds.) Brno:Masaryk University, 2017, pp. 106-114. Download original chapter (PDF)

4 The metaphor of collecting ‘emotional trading stamps’ until a person had ‘filled enough stamp books’ to cash them in by having a ‘justifiable outrage’ was Eric Berne’s brilliant capturing of the common emotion-accumulating process (Games People Play, 1964).

5 The format of this question is based on Penny Tompkins and my Problem-Remedy-Outcome model. There are plenty of examples of the ‘What would you like to have happen?’ question in action in these case studies.

6 Full transcript available at: cleanlanguage.com/from-pain-to-calm-clear-sky/

Further reading

Penny Tompkins & James Lawley:

The deconstruction of a client statement involving a force metaphor cleanlanguage.com/the-emergence-of-background-knowledge/ (1998)

Analysis of a client statement using force schema cleanlanguage.com/a-model-of-musing/ (2002)

The forces involved in the metaphor of ‘balance’ cleanlanguage.com/body-awareness/ (2004)

An overview of Mark Johnson’s schema and sample schema of some client statement cleanlanguage.com/embodied-schema/ (2009)

Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind, University of Chicago press, 1987.

Zoltán Kövecses, Metaphor: A practical introduction, Oxford University Press, 2002.

Zoltán Kövecses, Force dynamics, conceptual metaphor theory, emotion concepts. Draft paper dated 23 Dec 2020. Available from researchgate.net/publication/347437903

Walter De Mulder, Force Dynamics. Chapter 13 in The Routledge Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Eds. Wen & Taylor, 2021.