Pesented at The Developing Group 1 Oct 2011

This article is in two parts. It starts with a review of several theories about how we make (or take) decisions. Based on these ideas and our clinical experience we have created a practical process for how to ‘self-nudge’ which we describe in the second part.

Choice architecture for the mind

Richard Thaler & Cass Sunstein propose that those of us who have a responsibility for organizing the context in which people make decisions can be thought of as “choice architects”. They call their book Nudge because rather than attempt to control people’s behaviour, the authors “strive to design policies that maintain or increase freedom of choice” (p. 5).

Thaler and Sunstein give many examples of how to bias other people’s attention and hence their behaviour through the design of the physical environment. We think the same principles can be applied to influencing the landscape of our ownminds and behaviour. Rather than attempt to change our mind, we can aim to bias its ‘natural’ choices in directions that please us (and hopefully others). [1]

Who makes the decisions?

However, consider alternative evidence presented by Guy Claxton:

It begins to look as if the unconscious brain-body-context system (‘brain” for short) is in charge not just sometimes but all of the time. When [we take the evidence] seriously, we come up with an image of our own minds that places unconscious intelligence at the very centre, rather than on the margins. The [evidence points] to fundamental misconceptions in the Cartesian folk psychology of ‘normal’ human nature. The idea of the calm, well-lit Executive Office of rational consciousness as the mind’s centre of operations, occasionally interrupted by the id or inspired by the muse, is a misleading image. The brains behind the operation turns out to be the brain itself. (The Wayward Mind, p. 340)

And philosopher Daniel Dennett musing on the phenomenology of decision-making:

Are our decisions voluntary? … We do not witness [a decision] being made; we witness its arrival. Once we recognize that our conscious access to our own decisions is problematic, we may go on to note how many of the important turning point in our lives were unaccompanied … by conscious decisions. … Reminiscence shows that yesterday one was undecided, and today one is no longer undecided; at some moment in the interval the decision must have happened, without fanfare. (quoted in The Wayward Mind, p.347)

Claxton adds:

‘No activity of the mind is ever conscious’, said the great American psychologist Karl Lashley, though of course many of these activities generate consciousness. No intention is ever hatched in consciousness; no plan ever laid there. Intentions are premonitions, icons that flash in the corner of consciousness to indicate what may be about to an occur. As that wise sceptic Ambrose Bierce said in his Devil’s Dictionary, an intention is ‘the mind’s sense of the prevalence of one set of influences over another set; and the effect whose cause is the imminence, immediate or remote, of the performance of the act intended by the person incurring the intention’. (The Wayward Mind, pp. 340-341)

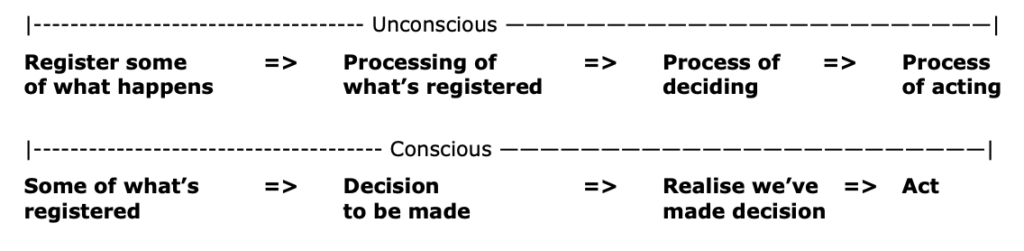

A more sophisticated model includes the role of the unconscious and parallel process:

Multiple drafts

Every situation and all language is pregnant with ambiguity. Thus there are always a variety of ways of interpreting experience. In order to handle the potential ambiguity, according to Daniel Dennett, the brain produces multiple simultaneous interpretations – “multiple drafts of narrative fragments” – each one being available to guide behaviour:

There is no single, definitive ‘stream of consciousness,’ because there is no central Headquarters, no Cartesian Theatre where ‘it all comes together’ for the perusal of the Central Meaner. Instead of such a single stream (however wide), there are multiple channels in which specialist circuits try, in parallel pandemoniums, to do their various things, creating Multiple Drafts as they go. (Consciousness Explained, p. 253-4)

At any point in time there are multiple drafts of narrative fragments at various stages of editing in various places in the brain. While some of the contents in these drafts will make their brief contributions and fade without further effect – and some will make no contribution at all – others will persist to play a variety of roles in the further modulation of internal state and behaviour and a few will even persist to the point of making their presence known through press releases issued in the form of verbal behaviour. (Consciousness Explained, p. 135)

We can only say one word at a time or do one or two behaviours simultaneously. Consciousness has a difficult time handling ambiguity (originally, ‘going two ways’) and is in real trouble when the choice rises to three or more equal options. Therefore, one of the drafts needs to become the final manuscript that guides our behaviour, and from which our conscious self makes sense of the world. In an emergent self-organising process, like Darwin’s natural selection, there is no central controller who selects any particular draft – the whole system ‘decides’.

The multiple drafts model suggests that until we actually act, our behaviour is poised to go in a number of directions; like a tennis player continuously gathering information about which way to move next, attempting to anticipate and yet wanting to delay their commitment to one direction until the very last moment. An equivalent process happens as we attempt to make sense of what someone is saying. We start making meaning from their very first utterance and each extra word and nonverbal subtly alters the meaning we make – until there’s a coalescent moment, ‘oh that’s what they mean.’ Dennett proposes that even those first hints of meaning are only the tip of an iceberg of possible meanings that are being considered by the brain.

Non-conscious processing

Neuroscientist, Antonio Damasio’s experiments reveal the extent of non-conscious processing in decision-making:

The task involves a game of cards, in which, unbeknownst to the player, some decks are good and some decks are bad. The knowledge as to which decks are good and which are bad is acquired gradually, as the player removes card after card from varied decks. The source of the knowledge is the fact that the picking of certain cards from certain decks leads to financial rewards or penalties. …

By the time normal players begin choosing consistently good decks and begin avoiding the bad decks, they have no conscious depiction of the situation they are facing and they have not formulated a conscious strategy for how to deal with the situation. At that point, however, the brains of these players are already producing systematic skin conductance responses, immediately prior to selecting a card from the bad decks. No such responses ever appear prior to selecting cards from the goods deck. These responses are indicative of a non-conscious bias. (The Feeling of What Happens, p. 301)

Claxton describes the classic experiments which suggest that an unconscious decision to act is taken some time prior to the conscious awareness of having taken the decision:

It even looks as if the brain has made up its mind what it is going to do next before it tells ‘you’. In some celebrated studies, the Californian neuroscientist Benjamin Libet rigged students up with EEG equipment that would show what was happening in their brains, and then asked them to make a voluntary movement, like moving a finger, when they wanted to. He also asked them to record the moment when they first experienced the intention to move. He discovered that the intention to move appeared about a fifth of a second before the movement began – but that a surge of activity in the brain reliably appeared around a third of a second before the intention!

Back in the 1960s, the British neurosurgeon Grey Water had relied on the same effect to create a most disconcerting experience. Some of his patients, for clinical reasons, had electrodes implanted in the motor cortex of their brains. Grey Water invited them to view a sequence of slides, at their own pace, by pressing a control button to advance the carousel to the next slide when they were ready. Unbeknownst to them, however, Grey Water had rigged the projector so that it was triggered not by the push on the button, but by their own anticipatory brain waves, so the slide began to change just as they were about to change it! The technology worked faster than the brain’s ability to concoct a corollary conscious ‘intention’, and the effect, according to his patients, felt very weird. (The Wayward Mind, pp. 257-8)

Hindsight dressed up as foresight

But how come, if “cerebral initiation of a spontaneous voluntary act begins unconsciously” to quote Libet, it appears that we decide and then act based on that decision? Hindsight dressed up as foresight, is one answer:

There is a good deal of evidence that the part of the unconscious brain that concocts explanations for why we did something – what neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga calls the ‘interpreter’ – is not the same part of the brain that decides to do it. The former part does not have direct access to the workings of the latter. All the interpreter can do is notice what you actually did, or felt, and then construct a plausible story about How Come. Gazzaniga suggests that for most of us the interpreter is located in the left hemisphere of the brain, and he has been able to show it at work in so-called ‘split brain’ patients, those who have had the two sides of their brain disconnected.

If you flash the word ‘Laugh!’ to one of these patients in such a way that it only goes into the right hemisphere, they laugh, but the left hemisphere does not know why because it did not see the word. If you ask the patient why they laughed, the interpreter, quick as a flash, makes something up. The patient says: ‘You guys come up and test us every month. What a way to make a living!’ And, … they do not know that this is confabulation – they genuinely believe that they are reporting the actual cause of their laughter. (The Wayward Mind, pp. 343-344)

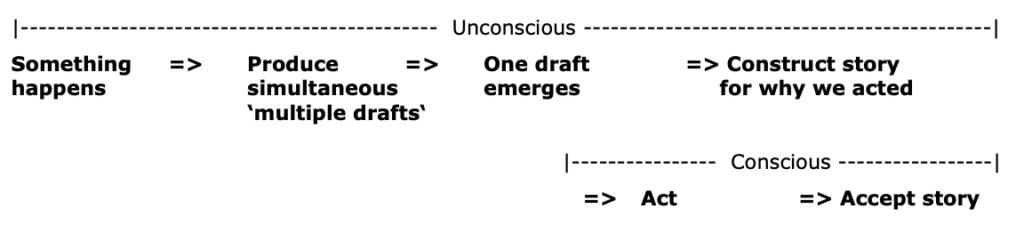

Decision-making may therefore look more like this:

This model not only recognises that the vast majority of ‘mental processing’ happens out of awareness it takes the radical step of shunting the conscious element from parallel to after the decision, and even after the action. [3]

Free will to do what?

The neuroscientist’s model is disturbing. Not only because we may have been fooling ourself for all these years, but because it seems to remove our ‘free will’ to decide to act.

If we accept the NLP dictum that “people make the best choice available to them given their model of the world” (Robert Dilts, Strategies of Genius, Vol 1, p. 305) then, in-the-moment, we have no choice but to take the ‘best choice’ available to us.

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela emphasise that “the nervous system functions as a closed network of changes” (The Tree of Knowledge, p. 164). This operational closure means that the system and the system alone specifies what counts as relevant, and a system cannot operate in a way that is not organised to do. Our decisions and actions can only be drawn from the existing organisation. Then how does the ‘outside’ world influence us and how to we decide to do something new?

I don’t know what it would feel like if my will were free. What on earth would that mean? That I didn’t follow my will sometimes? Well, why would I do that? in order to frustrate myself? I guess that if I wanted to frustrate myself, I might make such a choice – but then it would be because I wanted to frustrate myself, and because my meta-level desire was stronger than my plain-old desire. [And he concludes:] Our will, quite the opposite of being free, is steady and stable, like an inner gyroscope, and it is the stability and consistency of our non-free will that makes me me and you you, and also that keeps me me and you you. (I am a Strange Loop p. 340-341)

This challenge to the standard view of humans, rather than make us mere autonomons, requires us to have a different sense of self and to reconsider how we influence our own behaviour.

Influencing our own behaviour

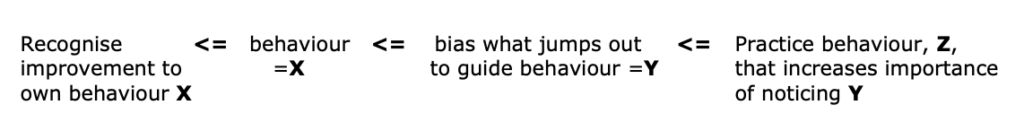

A participant on a recent clean facilitator training inadvertently provided a clue to how this might happen. When asked to explain her reasoning for choosing a particular client word to ask her clean question of, she said “it just jumped out at me”. This makes sense when we consider that our ‘conscious self’ is always the last to know. It also gives us a way to influence ourselves, not in the moment, but in advance.

If we can train our system to bias the things that ‘jump out’ we will automatically act in a preferred way, i.e. we can bias the way our future selves respond; even if at the time we are not consciously making decisions.

The consequences of this type of self-change go deep. Goal-setting will still be useful, but it becomes a context-definer or ‘dynamic reference point’ rather than an end to ‘aim for‘ and ‘move towards‘. Instead, we need to answer the questions:

What would need to ‘jump out’ that would mean I would respond in a way that I subsequently assessed as more beneficial for me / others / the planet?

How can I train my system to give those aspects sufficient salience that they are automatically triggered by the context?

We can diagram the process as (read from right to left):

You’ll see we are using the same ‘working backwards from the desired outcome’ logic as used by the necessary conditions vector and we are using adjacency.[4] Rather than going straight for doing the behaviour more often, we go ‘next to’ the behaviour to what jumps into our awareness, and then we go ‘next to’ that (what we need to do to increase our capacity to generate those signals). What we actually ‘practise’ may not look anything like the desired behaviour, and paradoxically may even look like it is going in the opposite direction. Remember the “wax on, wax off” part of the film The Karate Kid where the student doesn’t realise that cleaning the master’s car is training his marshal arts ability to defend himself automatically.

By the way, we realise the circularity of this explanation – how do we decide to practice? But circularity is the very nature of self-reflected consciousness. Douglas Hofstadter didn’t call his book I am a Strange Loop for nothing.How does practicing a behaviour, Z train our unconscious to make us aware of signal Y that will help us do more of the desired behaviour X? It is like part of the unconscious says ‘Oh I see, we are paying attention to these things now, I’ll keep an eye out for circumstances when I can nudge us in that new direction.’ On the other hand, the same part can notice that we have announced we are going to do X, but have put little time or energy into doing anything about it, so one of the other multiple drafts continues to take precedence. In effect we unconsciously think ‘this can’t be that important so I’ll keep nudging us in the direction we’ve been going in’.

This approach is particularly useful where we already have the behaviour within our repertoire and we would like to do it more often, more consistently, or more fully. If we have no experience of doing the behaviour (e.g. speaking a foreign language) we may need another method. Having said that, we suspect this approach would still be helpful since all expertise involves unconscious calibrating.

Setting an intention

In New Code NLP there is a strategy for self-influencing that is based on ‘setting an intention’. You ‘set an intention’ to do a particular behaviour and you let the unconscious mind figure out how and when to do it. (Ernest Rossi has a similar approach.) Setting an intention is different from goal-setting in that it is less focused on the outcome and more focused on the commitment. [5] The theory is that if we are consciously congruent when we set the intention, the unconscious will do the rest.

We think there is much merit in this approach and in practice we have noticed two potential flaws in the theory: Firstly, we are often far from fully congruent (if we were, we probably wouldn’t need to set our intention in the first place); and secondly, sometimes it just doesn’t happen as we would like – so then what to do? Reset your intention – more often, more intently?

Our model addresses these two issues. It acknowledges the major role played by non-conscious mental processes and it suggests that we can support the unconscious by raising the profile of the triggers that will lead to more of the required behaviour. But that may not be enough. Our research into self-deception shows how good we can be at fooling ourselves and ignoring evidence. To counter these tendencies we incorporated the notion of ‘undeniable evidence’ as part of the feedback to self.

What evidence is impossible for you to ignore and would undeniably let you know that you are, or are not, improving? [6]

The progress principle

A recent Oliver Burkeman Saturday Guardian column reviewed the research presented by psychologists Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer in The Progress Principle:

The striking conclusion is that a sense of incremental progress is vastly more important to happiness than either a grand mission or financial incentives – though 95% of the bosses didn’t realise it. Small wins “had a surprisingly strong positive effect, and small losses a surprisingly strong negative one.” Which chimes with recent research among US entrepreneurs by the business scholar Saras Sarasvathy: whatever they tell you on TV’s Dragon’s Den, the successful ones rarely made long-range business plans, and scorned market research. They went for quick wins – a few sales, then a few more – instead. Their philosophy was “ready, fire, aim”. [7]

As Burkeman says, “The challenge is remembering to notice the smaller things you’ve achieved” He suggests keeping a ‘done’ list, as well as or instead of a ‘to-do’ list. In his book Help!, Burkeman also notes that often “motivation follows action” rather than the other way round. (p. 116)

Calibrating what’s working

The previous Developing Group considered the question: How do you know when what you are doing is (or is not) working for the client? This is essentially the same question as: What do you want to automatically ’jump out’ and guide you while you are facilitating? What are you unconsciously calibrating?

As Robert Dilts demonstrated when he models, he knows what is essential because his ‘radar bleeps’ at him. He does not know (at that time) how he does, nor why it’s essential, he is only interested in the result which says ‘pay attention to this’. [8]

An essential element in the method of self-change we are proposing is self-calibrating whether what you are doing is working – or not. And what is the highest quality evidence on which to base our calibrations? What we actually do and the effect of that doing – i.e our patterns of behaviour and the lives we live. [9]

Example 1: remembering dreams

A well tried and tested example of how the process works comes from people who want to remember their dreams. This is a lovely example because remembering a dream is entirely reliant on unconscious process since we are not conscious when we dream. The simplest way to learn to remember your dreams is as follows:

- Make sure paper (e.g. ‘My Dream Journal’), pen and a light are within reach beside your bed.

- Just before you go to sleep, set an intention to remember your dreams, i.e. make a commitment to yourself.

- Whenever you wake up (whether in the morning or during the night) make your first action (even before you get out of bed) to reach for the pen and paper.

- Write down any dream fragment and whatever you are feeling in that moment.

- Now just wait – write down anything else that comes to mind that seems related to your recent dreams.

- Get up. If any other fragments come to mind during the day write them down.

- Repeat steps 1-6 every day.

Most people report that within a week or so they are remembering significantly more of their dreams. James found that within a few weeks he was remembering 4 or 5 dreams a night!

Example 2: lucid dreaming

An even more compelling example of how the process can work comes from people who want to be conscious during a dream – to have lucid dreams. The trick is to know what signals in a dream can trigger the conscious awareness “I am dreaming”, and to practice looking for them when you are awake!

By all accounts, the written word rarely stays constant in dreams. If you read something in a dream and then either read it again or just stare at the words they will dissolve or change. Also apparently we rarely look at our hands in a dream. So if you can train yourself to look at your hands in a dream and wonder if they are your real hands or your dream hands, that can be enough to activate your awareness of being in a dream. Since you cannot consciously practice these behaviours in a dream you have to practice them when you are awake. Every now and then, several times during the day, pause and look at what you are reading and look at your hands and wonder ‘Are these real or am I dreaming?’.

After repeating this behaviour you can find yourself asking yourself the same question in a dream – and if the answer is ‘I’m dreaming!’ you are conscious. It took James a couple of weeks before he was aware of questioning himself in a dream. The first few times it happened he was so excited he woke up! Eventually he learned to control the excitement and remain asleep and lucid during the dream.

The reason these two examples are so valuable is we have no option but to recruit the unconscious since we cannot consciously decide to remember a dream during the dream, and likewise, we cannot consciously decide to become conscious during a dream. Therefore we have approach the conundrum adjacently. In both cases, we (a) make a conscious declaration of intent; (b) practise behaviours which demonstrate to ourselves our seriousness and raise our ability to detect certain signals; (c) trust that our unconscious will do what it needs to when it needs to do it; and (d) take small successes as signs of progress and keep iterating round the process.

Example 3: Cognitive-bias modification

As often seems to happen, once you have an idea you realise others are doing much the same (Rupert Sheldrake would say this is not a coincidence but an example of ‘morphic resonance’). The Economist ran an article, headlined with typical hyperbole: ‘Therapist-free therapy: Cognitive-bias modification may put the psychiatrist’s couch out of business’. They report on computer programs that help retrain “unconscious cognitive biases”. Apparently, Cognitive-bias modification (CBM) as it is known, can have a positive effect on anxiety and addictions after only a few 15-minute sessions, and is now being tested with people who suffer from post-traumatic-stress disorder and depression:

CBM is based on the idea that many psychological problems are caused by automatic, unconscious biases in thinking. … The goal of CBM is to alter such biases, and doing so has proved surprisingly easy. A common way of de-biasing attention is to show someone two words or pictures—one neutral and the other threatening—on a computer screen. In the case of social anxiety these might be a neutral face and a disgusted face. Presented with this choice, an anxious person instinctively focuses on the disgusted visage. The program, however, prods him to complete tasks involving the neutral picture, such as identifying letters that appear in its place on the screen. Repeating the procedure around a thousand times, over a total of two hours, changes the user’s tendency to focus on the anxious face. That change is then carried into the wider world. (3 March 2011, economist.com/node/18276234)

Let us add a few more pieces to the pie.

A role for consciousness

The above cited research begs the question: what is the role of consciousness? Some scientists have suggested it is nothing but an ‘epiphenomenon’, a mere by-product that serves no purpose. We wonder if they really believe we would be living in mega-cities in the midst of a debt crisis if we had yet to evolve conscious awareness. The easiest way to see how central consciousness is to being human, is to see what happens when it is taken away or diminished. People who lose some of their faculty to be conscious through an accident, illness or degeneration often show major changes in behaviour and a shrinking of their life experience – not that they know it of course.

Inevitably, when we consider consciousness we have to consider our sense of self – ‘The thinker of the thoughts’, as we love hearing Deepak Chopra say. Scientists are pretty unanimous that there is no ‘ghost in the machine’, no ‘theatre of the mind’ where a little ‘homunculus’ lives. However, removing the idea of a controlling ‘I’, a decision-making CEO, doesn’t have to relegate consciousness from the Premiership into the non-league wilderness.

Consciousness, it seems to us, plays at least two vital and interlocking roles:

It influences what our system deems important or as the neuroscientists say ‘salient’. This sets up an amplifying feedback loop: What we attend to gains in salience which means we are more likely to attend to it, which means it gains in salience …. [10]

It also provides what scientists term ‘a workspace’ that enables the system to pause and reflect on itself – using memory as feedback and its creativity to feedforward – and to imagine things that have never happened. These reflections influence the future behaviour of the system – which can then be reflected on, and so on.

We know we concoct stories based on those reflections. We have little difficultly seeing that these reflections come afterthe fact, and are explanations. If we shrink the time scale down from reviewing events that happen hours, days or years ago to the constructing of post-behaviour ‘plausible stories’ in a fraction of a second, we can see how we might think the previous review was the cause of the next act, rather than the other way around.

Thinking systemically

Another way to approach the apparent conundrum is to apply systemic thinking. The above models are all linear. They use time to straighten out our perceptions into a beginning, a middle and an end. But if, instead of stopping at the ‘end’ we keep asking “And then what happens?” we find that the story loops round to eat its own tail. We get the same result if we keep asking ‘And what happens just before?’ the beginning. Our after-reflections can just as validly be seen as before-primings. In humans, because of consciousness, ‘feedback’ and ‘feedforward’ are inseparable sides of the same coin. [11]

Self-nudging: Biasing our unconscious mind

Summary of process

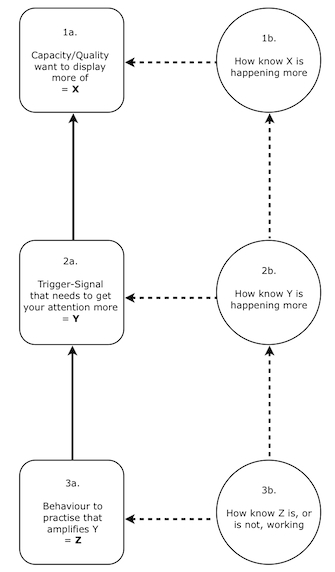

1a. Decide on the behaviour you would like to do more of (in particular contexts) =X.

1b. Identify how specifically will you know more X-ing is happening?

2a. Identify what needs to get your attention in-the-moment (trigger and signal =Y) so that you automatically tend to do more X-ing? (i.e what internal conditions will nudge you to do more of X?)

2b. Identify how will you know Y-ing is happening more?

3a. Identify several ways of practising how to get good at generating Y =Z.

3b. Identify undeniable evidence that will let you know whether you are making ‘incremental progress’ – or not.

4 Do Z regularly.

5. Put yourself in contexts where X will likely be required – and notice what happens:

- If you detect incremental progress do more of Z until you have demonstrated you are good enough at doing X and it has become a habit.

- If you detect no, or decremental progress, identify what other Y and/or Z are likely to have more influence, and repeat using those.

Figure 5

Process Notes

Robert Dilts calls this a ’generative’ process. It is about accessing and utilising more of an existing resource over time. It is not about being perfect or eliminating an unwanted behaviour. It is also not aimed at acquiring behaviours or capacities you do not yet have. [12]

X will be:

- a general skill/capacity/quality you’d like to apply (probably in contrast to your current path of least resistance which is to repeat the old pattern)

- required in different contexts, especially ‘unexpectedly’

- a desired way of being or behaving (it is not primarily a remedy or a solution to a problem)

something that you need to do repeatedly or to sustain over a long period.

Y will be:

- the combination of a ‘trigger’ and a ‘signal’ that alerts you to the presence of the trigger

whatever selects ‘drafts’ that leads to doing more of X.

Z will include:

- specific and simple behaviours which amplify Y, i.e. when repeated they lead to more Y

- designing of the environment to support Y happening.

process reviews (both short- and long-term)

The b’s in each part of the process above calibrate:

- The desired quality is happening more: frequently / effectively / efficiently / elegantly

- The signal is happening more: frequently / strongly / timely

The practising is having the desired effect.

Your commitment is to:

- do Z (and to trust that your system will select Y which will prompt X as and when appropriate)

- monitor the effectiveness of the process (notice small improvements)

- amend the process if it is not working.

Footnotes

1 Thaler and Sunstein suggest that there are some crucial points to remember in the design of choice contexts:

- “There is no such thing as a ‘neutral’ design” (p. 3)

- “Apparently insignificant details can have major impacts on people’s behavior. A good rule of thumb is to assume that everything matters. In many cases, the power of these small details comes from focussing the attention of users in a particular direction” (p. 3)

- “Never underestimate the power of inertia [and] that power can be harnessed” (p. 8)

- “People make good choices in contexts where they have experience, good information, and prompt feedback” (p. 9)

“Choosers are human, so designers should make life as easy as possible” (p. 13)

2 On the other hand, there are inbuilt binds ‘designed’ to keep us from changing our minds too easily. Someone who has over- or under-eaten for many years (especially if this started in childhood) will likley have coded ‘unhealthy’ as ‘normal’. That means whenever they attempt to change (or even to contemplate a change) towards ‘healthy’ it will feel ‘weird’, if not downright dangerous. To change, the person needs to recognise that they cannot trust their usual responses, so what do they trust instead? Learning to recalibrate signals is a challenge because it is a second-order change. It can take years to get to a healthy size and maintain that for long enough for it to become the new normal.

3 There is also a major role for inhibitory processes which will be addressed at the 7 July 2012 Developing Group,

4 See Metaphors in Mind pp. 201-203, formalized in our ‘Clean Framework for Change’ coaching process and our article: Proximity and Meaning: A Clean approach to adjacency.

5 See Judith DeLozier, Mastery, New Coding and Systemic NLP. Our PPRC model shows that ‘setting an intention’ puts the more focus on the Perceiver than the Perceived. See our Paying attention to what they’re paying attention to: The PPRC Model.

6 See our article: Learning to Act from You know to be True.

7 Oliver Burkeman, This column will change your life: small victories, 9 September 2011

8 See our article: Modelling Robert Dilts Modelling.

9 Our first ever article back in 1993 Your Thinking Virtually Creates Your Reality looked at what we called SRP, ‘the systemic reflective’ principle’. We explored how our out-of-awareness patterns of mind manifest themselves in our physical circumstances – how the map becomes the territory – and how this enables us to discover our blind-spots by looking at the circumstances we ‘create’.

10 See our articles: Attending to Salience and The Neurobiology of Space.

11 See our articles: Feedback Loops and Iteration, Iteration, Iteration.

12 Having said that, with a modification we can apply the approach to modelling and the acquisition of skills from exemplars – those people who impress us with their ability to do something: (1) Code the structure of the required behaviour; (2) Identify the criteria for how well the behaviour is working, or not, and the signals that get triggered by the presence of those criteria; and (3) Find ways of practising how to get good at generating #2. Also see James’ blog about modelling criteria, How DO you know?.

References

Burkeman, Oliver, Help! How to be come slightly happier and get a bit more done (Canongate, 2011)

Claxton, Guy, The Wayward Mind: An Intimate History of the Unconscious (Abacus, 2006).

Damasio, Antonio, The Feeling of What Happens (Vintage, 2000)

Dennett, Daniel, Consciousness Explained (Penguin, 1993)

Dilts, Robert, Strategies of Genius, Vol 1 (Meta Publications, 1994)

Maturana, Humberto & Francisco Varela, The Tree of Knowledge (Shambhala, 1992)

Hofstadter, Douglas, I am a Strange Loop (Basic Books, 2008)

Thaler, Richard & Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (Yale University Press, 2008)

John Martin informed the Clean and Emergent Research Group (29 Apr 2009) of some references for the experiments that show brain activity involved with a decision-making appears before we are consciously aware of making the decision. He said, “The easiest and most up to date source I have found is the very full Wikipedia article on Benjamin Libet. However my starting point was Rita Carter (2002) Consciousness, Chapter 3. She is a science journalist so it is a very readable book. The source references she gives are:

Benjamin Libet (1985) ‘Unconsciousness: Cerebral initiative and the role of conscious will in voluntary action’, Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 8, 529-66

Benjamin Libet (1999) ‘Do we have free will?’, Journal of consciousness studies, 6, 47

Patrick Haggard et al (1999) ‘On the perceived time of voluntary actions’, British Journal of Psychology, 90, 291-303

Patrick Haggard et al (1999) ‘On the relation between brain potentials and awareness of movements’, Experimental Brain Research, 126, 128-33.”

Postscript

Two months after this article was written, James wrote a short report on his use of self-nudge to regularly go out running.(something he had been trying unsuccessfully to achieve for over 20 years)

And there’s an update on progress from January 2014.