Having referred to ‘evolution’s arrow’ in my last blog, and having used same imagery in Metaphors in Mind (borrowed from Ken Wilber) to describe the:

“developmental, progressive nature of Nature, whose directionality is often represented by an arrow – an arrow that does not travel in a straight line, but one that spirals and meanders as it progresses.” (2000, p.176)

I thought I’d present an alternative viewpoint.

One of my heroes, the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould (co-originator of the concept of punctuated equilibrium) gives a different perspective in Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin (Three Rivers Press, 1996). He presents compelling evidence that the “progress of life” is really random motion away from simple beginnings, and not directed impetus toward complexity. Gould says that our intuitions, based on the standard ways of thinking about evolution are misleading and he asks us fundamentally reconceptualise our view of evolution – no easy thing to do.

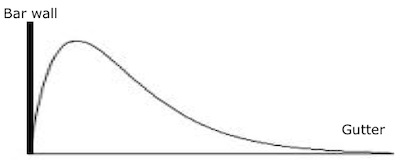

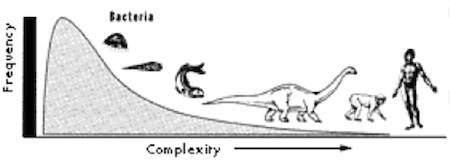

Gould shows that there is a “left wall” of simplicity which cannot be breached. Single-cell organisms live right next to the wall. From there, even completely random change will tend to drift away from the left wall of simplicity and towards increasing complexity. In typical Gould fashion he uses the analogy of a drunken man staggering out of a bar. Even if his steps are entirely random there will be an overall directionality. Since the wall of the bar stops him going in one direction, given enough time, the probability is he will move in the other direction – and end up in the gutter.

If you plot the likelihood of the drunk’s location you get a frequency distribution with a long right tail:

Gould’s thesis is that life generates examples of increasing complexity because, just like the drunken man, it has nowhere else to go. All sorts of things produce variation; and because there is a left wall of simplicity that variation will automatically give rise to more complex organisms. But that doesn’t mean there is an innate drive to ‘progress’. It means the long right tail of the curve is a consequence and not a cause.

Yes more complex organisms arise, but the vast majority of organisms on the planet are as simple as they ever were. Bacteria dominated the beginnings of life, they still dominate today, and they will dominate long after humans have become extinct. Because we can’t see them we underestimate them. (Did you know that 10% of your dry body weight consists of bacteria? Neither did I.)

Full House is not an easy read. It presents detailed evidence in a logically argued case that leads to clear conclusions – just like books used to. It also offers lots of interesting side-shoots. For example, Gould rails against the use of the same word for ‘biological evolution’ and ‘cultural evolution’ when the underlying mechanisms are so widely different (Darwinian vs. Lamarckian). He also reminds us of the “unpredictability and contingency” of any particular event in evolution. If we could rewind the tape of life and play it again there is almost no chance of repeating the “glorious accident” of Homo sapiens.2

I can see parallels between Gould and Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s ideas that we are Fooled by Randomness and the occasional Black Swan resulting in misleading intuitions based on statistical misconceptions.

Why bother with all this? If we are going to learn to think systemically then we need to think in terms of whole systems. Writers like Gould challenge us to think wider, longer and deeper about systems and how they change (evolutionary dynamics). To do this we need to set aside our ‘common sense’ and ‘it’s obvious’ intuitions (except within the narrow range of contexts in which they apply). And as I once heard Mary Catherine Bateson say, thinking systemically needs constant reinforcement to counter the daily bombardment by thousands of ideas that are born from simplistic and linear mindsets.

So, does biological evolution drive life to ever higher levels of complexity and progress, or is the growth in complexity an incidental consequence of life’s simple origins followed by successful expansion away from the left wall? Don’t ask me, it’s a complex subject!

Notes

1 Average life expectancy at birth in 1850s USA was 38, but those that survived childhood could expect to live into their 60s. Most people either died as a child or old age, not 38. The average in this case doesn’t tell you very much. Similarly, although average life expectancy has doubled since then, people are only living a few years longer, because almost all of the increase is due to less children dying.

2 “If one small and odd lineage of fishes had not evolved fins capable of bearing weight on land, terrestrial vertebrates would never have arisen. If a large extra terrestrial object had not triggered the extinction of dinosaurs 65 million years ago, mammals would still be small creatures, confined to the nooks and crannies of a dinosaur’s world, and incapable of evolving the larger size that brains big enough for self-consciousness require. If a small and tenuous population of protohumans had not survived a hundred slings and arrows of outrageous fortune (and potential extinction) on the savannas of Africa, then Homo sapiens would never have emerged to spread throughout the globe. We are glorious accidents of an unpredictable process.” (Full House, p. 216)