Contents

Section 1: Introduction

Section 2: Learning how to do a modelling project

Section 3: Defining a modelling project

Section 4: Stage 1: Preparing to do a modelling project

Section 5: Stage 2: Gathering information

Section 6: Stage 3: Constructing a model

Section 7: Stage 4: Testing your model

Section 8: Stage 5: Acquiring the model

Section 9: References

Our other articles about modelling are available at: cleanlanguage.com/category/md/

1. Introduction

The following is an in-depth summary of over 25 years experience of modelling: formal projects, informally, therapeutically and training modelling. These ideas are presented as background information and a checklist for conducting a full-scale modelling project. There are many, many less formal ways to make use of modelling.

Origins

The field of NLP (Neuro-Linguistic Programming) was established as a result of several modelling projects conducted by Richard Bandler and John Grinder. They, in collaboration with others such as Judith DeLozier, Leslie Cameron-Bandler, David Gordon, Robert Dilts did much of the original work to codify the process of modelling sensory and conceptual domains.

A more extensive list of collaborators was published in 2012: The Origins of Neuro Linguistic Programming edited by John Grinder and Frank Pucelik.

Modelling methodologies

There is not one way to model. The list below contains over a dozen modelling methodologies that to varying degrees we have had first-hand experience – although we would not claim to be experts in any (ok, maybe Symbolic Modelling!).

We have loosely classified the methodologies under the three headings (Sensory-Physical, Conceptual-Perceptual, Metaphoric-Symbolic). We first introduced these distinctions in our article Meta, Milton and Metaphor: Models of Subjective Experience (1996).

We used sensory and conceptual modelling to study David Grove at work, and as a result discovered a new way of modelling never previously documented which we called Symbolic Modelling.

Sensory-Physical modelling

| Modelling Methodology | Exemplar Modeller | Resources |

| Unconscious Uptake / Assimilation | John Grinder | Book: Whispering in the Wind (Grinder & Bostic St Clair, 2001) Videos: Article: Mirror Neurons: The neuro-psychology of modelling, (Thompson & Collingwood, 2013, NLP Magazine #09) |

| Deep Trance Identification | Steve Gilligan | Article: Interview with Steve Gilligan Book: Generative Trance: The Experience of Creative Flow (Gilligan, 2012) |

| Somatic Modelling | Judith DeLozier | Book: NLP II: The Next Generation: Enriching the Study of the Structure of Subjective Experience (Dilts & Delozier, 2010) |

Conceptual-Perceptual modelling

| ‘Teach Me’ | Richard Bandler | Book: Magic in Action (Bandler, 1992) |

| Analytic Modelling | Robert Dilts & Todd Epstein | Book: Tools For Dreamers (Dilts & Epstein, 1991) Books Strategies of Genius Volumes I, II & III (Dilts, 1994/1995) Book: Modelling with NLP (Dilts, 1998). Article: Overview of Modeling in NLP (Dilts, 1998). |

| Experiential Array | David Gordon & Graham Dawes | Book & DVD: Expanding Your World: Modeling the Structure of Experience (Gordon & Dawes, 2005) Website: expandyourworld.net |

| Developmental Behavioural Modelling | John McWhirter | Article: Re-modelling NLP: Part Fourteen: Re-Modelling Modelling (McWhirter, Rapport 59, 2002) |

| Cognitive Behavioral Modelling | Charles Faulkner | Download Article (PDF): Modelling an Expert; The missing piece in Knowledge Management (Faulkner & Modrall, 1998) |

| Meta-Levels | L Michael Hall | Book: Going Meta: Advanced Modelling Using Meta-Levels (Hall, 1997/2001) |

| Advanced Behavioral Modeling | Wyatt Woodsmall | Book: The Science of Advanced Behavioral Modeling (1998) and a set of 16 DVDs with the same title from a 2003 training Article: Modeling With NLP: Capturing and Transferring Expertise in Organizations (Feustel & Woodsmall, 2001) |

Metaphoric-Symbolic modelling

| Design Human Engineering | Richard Bandler | Book: Persuasion Engineering: Sales & Business Sales & Behavior (Bandler & La Valle, 1996) |

| Population Modelling | Lucas Derks | Book: Social Panoramas: Changing the Unconscious Landscape with NLP and Psychotherapy (Derks, 2005) |

| Symbolic Modelling | James Lawley & Penny Tompkins | Book: Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling (Lawley & Tompkins, 2000) Website: cleanlanguage.com including an extensive report with video clips of their Modelling Robert Dilts Modelling (2010). |

| Modelling Shared Reality | Stefan Ouboter | Article: Modelling Shared Reality (van Helsdingen & Lawley, Kwalon Vol 3, October 2012) |

| Systemic Modelling | Caitlin Walker | Book: From Contempt to Curiosity (Walker, 2014) Websites: trainingattention.com cleanlearning.com |

2. Learning how to do a modelling project

Why Model?

Modeling is a doorway into the vast storehouse of human experience and abilities, providing access to anyone willing to turn the key. For the individual who pursues modeling, this means:

- Access to an ever-widening range of new experiences and abilities

- An increasing ability to bring those experiences and abilities to others.

- A finer understanding of the structure underlying unwanted experiences and behaviors so that you know precisely what to change in those experiences and behaviors.

- Ever-increasing flexibility in your experience and responses.

A growing appreciation of the beauty to be found in the patterns of human experience.

There is an excellent article, Why Model? by Joshua M. Epstein based on his 2008 keynote address to the Second World Congress on Social Simulation.

Your outcomes

If this is your first attempt at conducting a modeling project (perhaps you are on an NLP Master Practitioner course) remember, your primary outcome is to become familiar with the basics of NLP modelling. Until you have completed your first project from start to finish you cannot know what is involved.

Your evidence that you have achieved your learning-to-model outcome will come in four forms, each demonstrating a higher level of competency.

1. The MINIMUM is that you:

(a) Demonstrate you have acquired a model of modelling that enables you to:

- Specify, plan and implement your modelling project

- Gather information appropriate to the desired outcome of the project

- Construct and document a model from the information gathered

Test the model’s effectiveness at reproducing the required results.

(b) Describe the difference having learned to model makes to you.

2. PREFERABLY you will also demonstrate that you can use the model you have constructed to reproduce results similar to your exemplar(s).

3. POSSIBLY, you will demonstrate that you can devise an approach which enables others to acquire your model (and facilitate them to acquire it).

4. ULTIMATELY, you will demonstrate that the acquirers are able to reproduce results similar to your exemplar(s).

Learning to model

Modelling, and learning to model, are highly systemic processes. Modelling is a type of learning, and therefore learning to model is ‘learning to learn’.

You will realise very quickly that modelling is an iterative process. That is, the results of each activity feed back into other processes, which are modified by the new input. The now modified processes feed forward to the next operation, which feeds back, and so on. For example:

I decide on an outcome for my modelling project. This largely determines the information I gather from my first exemplar. The learning that comes from gathering that information means I change the emphasis of my outcome. Both the revised outcome and the learning from the first gathering of information influences how I gather information from my second exemplar. This in turn may alter my outcome, it may help me to see some gaps in the information gathered from my first exemplar, and will certainly influence how I gather information from my third exemplar, and so on, and so on.

Learning to be comfortable with not-knowing, managing an abundance of information and ambiguity about what to pay attention to, especially in the beginning of a modelling project – are prerequisites for becoming a master modeller.

3. Defining a modelling project

What is modelling?

Modelling is a process whereby an observer, the modeller, gathers information about the activity of a system with the aim of constructing a generalised description (a model) of how that system works. The model can then be used by the modeller and others to inform decisions and actions.

The purpose of modelling is to identify ‘what is’ and how ‘what is’ works to produce the observed results – without influencing what is being modelled. The modeller begins with an open mind, a blank sheet and an outcome to discover the way a system functions – without attempting to change it.

[Note: We recognise this is an impossible outcome, since the observer, by simply observing, inevitably influences the person being observed. However this does not affect the intention of a modeller to not influence.]

Steven Pinker in How the Mind Works (p. 21) uses an analogy from the world of business to define psychology, but he could just as easily be describing the modelling process:

Psychology is engineering in reverse. In forward-engineering, one designs a machine to do something; in reverse-engineering, one figures out what a machine was designed to do. Reverse-engineering is what the boffins at Sony do when a new product is announced by Panasonic, or vice versa. They buy one, bring it back to the lab, take a screwdriver to it, and try to figure out what all the parts are for and how they combine to make the device work.

Pinker is not saying that people are machines. He is saying the process of making a model of human language, behaviour and perception can be likened to the process of reverse-engineering.

When ‘the system’ being observed is a person, what usually gets modelled is behaviour that can be seen or heard (sensory modelling), or thinking processes that are described through language (conceptual modelling). Figuring out how great tennis players serve is an example of the former, while identifying their beliefs and strategies for winning is an example of the latter.

What constitutes a learning-to-modelling project?

In general, almost anything that interests or excites you enough to want to acquire another way of doing, being, feeling, thinking, believing, etc. We recommend you go for something that will really make a difference in your life – and/or others’ lives too.

You need to choose a topic where you have sufficient access to your exemplars. And you need to remember that your primary purpose is to demonstrate you are learning how to model. The project is the primary means by which you will acquire that learning and then be able to demonstrate your learning.

As a minimum, you need to show that you can model patterns of:

External behaviour

Internal states

Internal processes

One of the most interesting parts of the process will be selecting the ‘chunk size’ of the project. This will require you to balance your desire to acquire some big chunk skill with the resources available within the time scales. As a general rule, people learning to model initially overestimate what they can achieve (i.e. the try to model too big a chunk) and they underestimate the value of modelling a small chunk in depth.

It’s OK to start with a big chunk outcome and refine it as the project progresses. In fact, it is common not to discover “the difference that makes the difference ” (Bateson) until well into the process. But when you do, that piece should become the focus of your project.

Definition of terms

| Result | The outcome (of a pattern of behaviour) which can be described in sensory specific terms. |

| The model | An abstract formulation constructed from the information gathered from modelling the exemplar(s) which when actioned by an acquirer produces a similar class of results. |

| Exemplar | The person (or group or organisation) that consistently achieves the results the modeller is seeking to reproduce. (In the early days of NLP, also referred to as ‘a model’.) |

| Modeller | The person who gathers information from the exemplar, constructs the model, and tests its effectiveness, efficiency, elegance and ethics at reproducing similar results (usually by first acquiring the model themselves). Sometimes they then facilitate others to acquire the model. |

| Acquirer | The person (usually including the modeller) who ‘takes on’ the model and attempts to reproduce results similar to those obtained by the exemplar. The acquisition process usually needs to be facilitated by an accompanying narrative, metaphors and activities. |

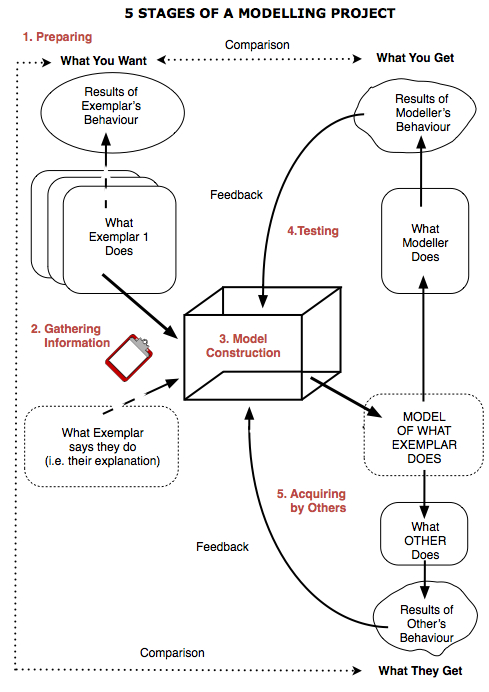

| Modelling | The process of gathering information from an exemplar, constructing a model, and testing its effectiveness at reproducing similar results (which requires someone to have acquired it). See Figure 1. |

| Modelling project | Both the plan for accomplishing the production and acquisition of a model, and implementation of that plan. We distinguish five stages that do not necessarily happen in this order:

|

| Self-modelling | The process of a person constructing a model of how they achieve the results they get. Facilitating the exemplar to self-model in Stage 2 is often a very efficient way of gathering information. At Stages 3 and 4, the modeller self-models as a way of making explicit the out-of-awareness information they have gathered. During Stage 5, the acquirer can self-model their response to acquiring an unfamiliar model. [NOTE: A major light bulb moment occurred when we grasped the implication of Michael Breen’s statement (at the London NLP Practice Group in about 1993): “All modelling is self-modelling.”.] |

Five Stages of a Modelling Project (Figure 1)

4. Stage 1: Preparing to do a.modelling project

Your first task is to define your modelling project by specifying its:

Overall Outcome

What examples of excellence (impressive results) have you noticed other people achieve in the world that you would like to achieve?

Sensory specific evidence of completion

How will you (and others) know you have got these results?

Scope of project

What is included and what is not.

Time scale

Context

In which you (and others) want the results.

Definition of terms

Value to you

What’s important to you about being able to consistently reproduce the results specified above?

Exemplars

Who are the people who consistently demonstrate the results you want?

What is your evidence that they are exemplars (of excellence)?

How will you get access to these people?

Be careful how you define your criteria for an exemplar. One modeller discovered the organisation that commissioned a modelling project picked their ‘top performers’ by how much they contributed to the ‘top line’ (revenue). The modelling revealed that some achieved it at the expense of others – they burned relationships – and were not building the collaborative culture the organisation wanted.

Presuppositions

What are you presupposing to be true before you start?

What metaphors are you using to describe your project?

How do you describe the project to exemplars using minimal presupposition and metaphor? (Hint: think context and behavioural examples.)

Your second task, is to plan how you are going to gather the relevant information.

To help you do that below we’ve reproduced the table from Introducing Modelling to Organisations (1998). It explains the chart below, The Who, Why, How, What, Where and When of Modelling which uses two of Robert Dilts’ frameworks to consider a modelling project from a number of perceptual positions and Logical Levels.

See also James’ blog: Choosing a Modelling Project (2014).

| I D E N T I T Y |

Who are you (what is your identity)? – Before the project – While modelling – After the project is over? |

Who is the subject of the modelling? – One person – Group of people – An organisational system |

Who else is involved? – Recipient of skills etc. – Trainers / recruiters – Colleagues / Customers |

| B E L I E F |

Why are you modelling? – What is the outcome for you? – What will you gain? |

Why model the subject? – What is your outcome for the subject? – What is the subject’s outcome? |

Why are you modelling? – What are others outcomes? – What will the organisation gain? |

| C A P A B I L I T Y |

How will you model (what skills are needed for each stage)? – 2nd Position Modelling – 3rd Position Modelling – 1st Position Modelling |

How will the subject(s) demonstrate what you want to model? |

How will the competencies be acquired by others? – How will you know they have them? – What methods will you use? |

| B E H A V I O U R |

What will you do at each stage of modelling? 1. Preparation 2. Information Gathering 3. Model Building 4. Testing 5. Transfer |

What is to be modelled? Behaviour Skill Thinking strategy Belief/Value/Attitude Perception/State |

What will other people need to do to acquire the skills, strategies etc.? |

| E N V I R O N S |

When and Where will the results of your modelling exist, and in what form? |

When and Where will the subject be modelled? |

When and Where will you present the results of your modelling, and in what form? |

5. Stage 2: Gathering information from your exemplars

Types and reliability of information

It is important to distinguish between different types of information gathered from the exemplar. The following five are in descending order of reliability of information:

- Observed behaviour with sufficient repetitions to indicate a pattern

- Observed behaviour with insufficient repetitions to indicate a pattern

- First-person descriptions or role-play by the exemplar of what they do

- Explanation by the exemplar (i.e. the exemplar’s conscious model of what they do)

- Second-hand descriptions*

* Sometimes, the experiences of those who interact with the exemplar are valuable, e.g. Cricket Kemp and Caitlin Walker modelled teachers who were especially adept at working in multi-cultural classrooms. Some of the key pieces of their final model came from interviewing the pupils.<

Ways to gather information

The general rule is, the closer (and more often) you get to observe the exemplar achieving the results the better. Sources of information can be:

- ‘Live’ observation of exemplar achieving their results (by 3rd position observation and/or 2nd position shadowing)

- Video/audio tapes, or material written by the exemplar that demonstrates achieving the required results

- Face-to-face interview

- Role-plays and mini-scenarios

- Questionnaires

- Written information edited or co-written by someone else

Description by someone else, e.g. biography.

While gathering information it is preferable that your questions are asked from within the frames and logic of the exemplar’s experience.

Fundamental or universal ways humans make sense of the world

‘Experience’ is a unified whole. Yet tobe conscious of our map ofthe world we categorise, evaluate, compare, decide, reason, intuit,etc. These processes require us to delete, distort and generalise(Bandler & Grinder). The most common way to do this is touse one domain – usually our everyday experience of the physicalworld – to make sense of another domain, usually the non-physicalworld. In other words, we use metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson). Themost commonly used metaphors, which appear to form the basis of alllanguages, are:

| Space | Relative location. |

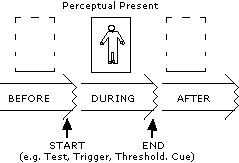

| Time | Sequence of events defined by a before, aduring, and anafter.

Figure 2: Schematicof a Sequence of Events |

| Form | The attributes or qualities by which something isperceived, and at the same time, distinguished from otherthings, i.e. how it is known. The content of ourperceptions. |

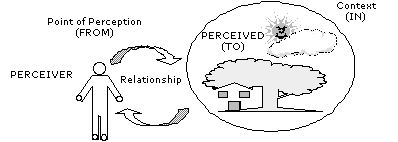

| Perceiver | The someone who is perceiving the something. To do thisthe perceiver needs a ‘means of perceiving’ (seeing,hearing, feeling and other ways of sensing) and a ‘point ofperception’ (where the perception is perceived from). Th eperceiver is therefore always in a certain relationship withthe form of the perceived within agiven context (time and space).

Figure 3: Perceiver-Perceived-Relationship-Context (PPRC Model) [Note: This model isour synthesisof David Grove’s “Observer-Observed-Relationship between” and John McWhirter’s “FROM-TO-IN” models.] |

| Level | Levels are a means of ordering and categorising experience in a hierarchy. They are therefore usually referred to as ‘Levels of’ something e.g. Learning, Organization, Abstraction, Explanation, etc. |

A modeller's perspective

One vital aspect of modelling rarely made explicit is the perspective adopted by the modeller when modelling an exemplar for an ability or pattern of behaviour. There are a surprisingly large number of modeller perspectives to choose from. Below we describe six (for more explanation of these see: A Modeller’s Perspective, 2014):

| Category | Modelling Methodology | Expert Modeller | Modeller’s Perspective |

| Sensory | Original NLP Modelling Generative Trance | John Grinder Steve Gilligan | Unconscious uptake/assimilation Deep trance identification |

| Conceptual | Analytic Modelling Experiential Array Sub-modality Modelling | Robert Dilts Gordon & Dawes Richard Bandler | Take on Step in and try on Teach me to be you |

| Symbolic (Metaphoric) | Symbolic Modelling | Lawley & Tompkins | Facilitating self-modelling |

| Modeller’s Perspective | Role of Exemplar | What is primarily modelled | Where/how modeller creates their model |

| Unconscious uptake / assimilation | No active part | External behaviour in a typical context | Unconsciously in the body and mind of the modeller |

| Deep trance identification | No active part | Identity (become the exemplar) | Unconsciously as if they are in the body and mind of the exemplar |

| Take on | Describes his or her experience and verifies modeller’s model | Internal process and external behaviour during interview | Consciously in the mind and body of the modeller |

| Step in and try on | Describes his or her experience and verifies modeller’s model | Internal behaviours, criteria and beliefs | Between modeller and exemplar – the modeller then steps into the model, tries it on and steps out |

| Teach me to be you | Explains to modeller how to do what they do | Internal process and sub-modalities | Consciously in the mind of the modeller |

| Facilitating self-modelling | Self-models, i.e. they create and describe a metaphor landscape in and around them self. | Organisation of verbal and nonverbal metaphors | In and around the exemplar maintaining the exemplar’s perspective |

Modelling questions

Every question directs the exemplar’s attention to some where,when or what in their mindbody map. So it is vital to consider:

- What kind of information do I want to gather?

- Where does the exemplar’s attention need to go to access that information?

- How simply (cleanly) can I ask for that information?

- Did I get the kind of information I was going for?

High-quality modelling questions tend to:

- Relate to the project outcome

- Make minimal presuppositions about the content of the exemplar’s map

- Be short and contain a minimal number of non-exemplar words

- Be simple and ask for one class of experience at a time

- Invite the exemplar to remain in the appropriate state to demonstrate what they do, i.e. in their ‘perceptual present’

- Not ask the exemplar’s attention to jump too far (in space or time)

- Not get ‘no’ or disagreement for an answer.

- Start from what the exemplar consciously knows, move towards the boundary of what is already known, before stretching that boundary into areas of the yet-to-be-aware-of (i.e. tacit knowledge).

The following are examples of some commonly used modelling questions:

| Identifying | How do you know …? |

| Context |

Where do you …? When do you …? Under what circumstances do you … / does … happen? |

| Intention |

For what purpose do you …? |

| Operations |

How do you normally go about …? How specifically do you do …? What’s the first thing you do …? Then what do you do? What do you do next? What do you need to do to …? |

| Evidence/ Test |

How do you know you are (achieving) …? How do you know you have (achieved) …? What let’s you know to …? What do you see, hear and/or feel that lets you know …? |

| Motivation/ Enablers |

What’s important to you about …? What makes it possible for you to …? What does … lead to or make possible? |

| Exceptions |

What do you do if it doesn’t go well / doesn’t work? How do you know to stop trying to (achieve) …? Under what circumstances would you not …? |

Clean Language

In addition to the above, David Grove’s Clean Language is ideal for modelling because it …

- Makes maximum use of an exemplar’s terminology.

- Conforms to the logic and presuppositions of an exemplar’s constructs.

- Only introduces ‘universal’ metaphors of form, space and time.

- Only use nonverbals congruent with an exemplar’s nonverbals.

Basic Clean Language modelling questions

[ ] = Exemplar’s exact words

| Identify | And how do you know [ ]? And that’s [ ] like what? |

| Develop Form | And what kind of [ ] is that [ ]? And is there anything else about [ ]? And where/whereabouts is [ ]? |

| Relate over Time | And what happens just before [event]? And then what happens? or And what happens next? |

| Relate across Space | And when/as [X], what happens to [Y]? |

Specialised Clean Language modelling questions

(also called Contextually Clean questions)

used only when the logic of a client’s metaphor permits

| Identify | And what determines whether [X] or [Y]? And what needs to happen for [event]? And is there anything else that needs to happen for [event]? |

| Develop Form | And what happening [location/event]? And does [an ‘it’] have a size or a shape? And how many [group] are there? And in which direction is/does [movement]? And where is [perceiver] [perceiving word] that from? |

| Relate over Time/across Space | And where does [ ] come from? And is [X] the same or different as/to [Y]? And is there a relationship between [X] and [Y]? And what’s between [X] and [Y]? And what happens between [event X] and [event Y]? |

Stage 3: Constructing Your Model

When modelling multiple exemplars for a class of experience, one process for constructing your general model is to:

1. Describe from their perspective and in their words how each exemplar does what they do to get the required results; i.e. construct models for each exemplar using their descriptions.

2. Evaluate each model for:

Coherency – The relationships between components adhere to an internal logic. It answers ‘why?’ questions from within its own logic.

Consistency – It will get similar results even when circumstances change. It can answer ‘what if?’ questions.

Completeness – It has all necessary distinctions/components. It answers ‘what else?’ questions with “nothing”. You can evaluate the degree to which your model is complete:

When no new components or patterns emerge and the exemplar’s descriptions add no further information about how that operational unit works.

When new components or examples continue to appear but they are isomorphic (have the same function or organisation) as previously identified patterns.

When the logic of the exemplar’s description encompasses an entire configuration, a complete sequence or a coherent set of premises (with no logical gaps).

When the model enables you to predict ways of dealing with unexpected situations, difficulties, interference or distractions that have yet to be mentioned by the exemplar.

3. Compare and contrast individual models component-by-component, step-by-step and function-by-function.

Begin to separate the information gathered from the exemplar: It is no longer their model, it becomes your model because you will represent the information in a different way to them, inorder to meet your modelling outomes.

4. Design your own model using one or more of the following methods.

a. Identify similarities across exemplars and construct a composite model based on similarities.

b. Use one of the models as a prototype and improve it by adding/substituting distinctions/components/steps from the other models.

c. Deconstruct the individual models into the function of each component/stage and construct a new model from the bottom-up.

d. Adapt existing compatible models from other contexts and use them as the framework for your model (e.g. ‘transformational grammar’ was the basis for the Meta Model, and ‘self-organising systems theory’ formed the framework for Symbolic Modelling).

5. Evaluate and improve your model based on the degree to which it is:

Effective – It gets similar results to the exemplars.

Efficient – It requires the least number of steps/components (use Occam’s Razor to make it “as simple as possible, but no simpler”).

Elegant – It is code congruent, i.e. the content of the model, the manner in which it is presented/coded and the means of getting the results are congruent.

Ethical – The effects are aligned with your and others’ existing or desired values.

[NOTE: We borrowed the first three E’s from John McWhirter and added the fourth ourselves]

And, evaluate whether distinctions/components are necessary by the degree to which each is:

Effective – contributes to the overall outcome of the model.

Efficient – serves multiple functions.

Elegant – fits into the overall coherency (internal code congruency) and enhances the consistency (external code congruency) of the model. It is compatible and aligned with:

The exemplars (Stage 2)

Itself (Stage 3)

The context where it will be tested (Stage 4)

The acquirers (Stage 5)

6. Test, get feedback, adjust model; test again, get feedback, adjust; etc. …

More on model construction

Exemplar’s cannot not do their patterns of excellence. A key aspect of modelling is to determine how an exemplar keeps achieving the same results even under changing circumstances. How is it that they cannot not do it? How come they don’t forget to do it? How do they adjust for unfavourable circumstances and still get consistently excellent results? In other words, how is it habitual? This information will not be in any of the components, but in the pattern of relationships between perceptual components. It will likely be the circular chains of relationships (Bateson) that keep the pattern repeating. And if so, your model needs to have comparable circular chains.

You can consider: ‘Is there any way I can adopt this model and do something else?’ and ‘Under what circumstances would I not get the required results?’. Adapting your model to take these circumstances into account will make it more robust, and more consistent.

Except when, under inappropriate or extreme conditions, the pattern breaks down. At these times a values or ethical threshold is often involved. What are those conditions and what do exemplars do then? Bateson warned that anybehaviour taken to extremes will become toxic. What are you own values and ethical limits with regard to using this model? These are non-trivial questions that we believe need to be openly and honestly considered.

7. Stage 4: Testing your Model

Different forms of testing occur throughout the modelling process. The primary purpose of testing is to get feedback from:

The exemplars

Yourself

The ‘real world’

Other acquirers

Test your model with the exemplar

a. Test the components and steps of your model for accuracy.

As you gather information from your exemplar you can recap (in their words) as much of your model of their behaviours, abilities and states as you have. This will give them a chance to evaluate your description for accuracy.

Use your sensory acuity to calibrate that the pace of your description enables the exemplar to ‘try on’ your model of them so they can compare it to their own experience, component-by-component and step-by-step.

Every response you get from your exemplar is feedback as to the accuracy of your model. They are the world’s expert on their model, and at this stage, that’s what you are attempting to reproduce. Anything they think is confusing, illogical, or that doesn’t fit, is a signal that your model is incomplete.

b. Test the logic of your model for accuracy

After you have confirmation of the accuracy of your model from the exemplar, you can start to make predictions as to what the exemplar would do in some as yet unspecified context.

The aim is to test if your understanding of the exemplar’s logic enables you to go beyond what you have been specifically told or observed.

Test your model on yourself

‘Try on’ your model by ‘running it through’ your system

Can you run the model – from ‘before’, when the starting Test criteria are triggered, through ‘during’ the Operations, until the ending Test criteria are met, and on to Exit‘after’ (TOTE model)?

Would you expect to get the required results?

Does it all fit together?

Can you break it – under what conditions would you not get the required results?

Are there other contexts where the process would also be applicable?

At this stage you are acquiring the model ‘for the moment’. You are not seeking to integrate it with any other models, instead you ‘put them aside’ while you run your tests. In other words, you are self-modelling to obtain feedback from your own system.

Test the model for real

Having used your own neurology to test your model your outcome changes. You now seek to test for the degree to which you can reproduce the required results. You want to compare the results you get with the results your exemplars get. To do this you need feedback from the external world. Two ways to do this are:

a. Prepare safe ‘test conditions’

Taking into account the ecology of the wider system and depending on the potential effects of your model not working, you may want to establish some ‘test conditions’ in which to test the model’s efficacy and your competency.

b. Go ‘live’

The ultimate personal test. Can you get similar results to your exemplars under similar conditions? And can you do that consistently and under a variety of conditions? Steve Andreas said that when he constructed a new model for change, (i.e. a new NLP technique) he had to test it out with 20-30 clients before he was confident it would account for the majority of cases.

Remember, your model may work perfectly but you may not yet have enough background knowledge or experience of running it to get the same results as your exemplars. Acquiring Einstein’s problem solving strategy won’t make you an Einstein overnight, but you can expect it to give you access to a different way of thinking about problems and to a wider range of solutions than you had before.

Other acquirers testing the model

If your modelling project is for other people (who were not involved in Stages 2-4), your outcome for testing changes again. Your design for an acquisition process (Stage 5) should include testing by the acquirers. The feedback you want now is: To what degree are the results the acquirers get similar to those achieved by your exemplars.

And to reiterate: Test, get feedback, adjust model; test again, get feedback, adjust; etc. …

8. Stage 5: Acquiring the Model

Over the history of NLP the metaphors used to describe Stage 5 have changed from:

Installation of the model by the modeller in the acquirer

to

Transmission of the model by the modeller to the acquirer

to

Acquisition of the model by the acquirer (facilitated by the modeller).

Interestingly, these changes seem to parallel a general trend within NLP; that is, the focus of the practitioner-client relationship is moving away from the practitioner and towards the client. We support this trend, since our preference is for the acquirer (to be facilitated) to self-model their own process of acquiring.

Acquiring presents a paradox: The exemplar gets their results largely through unconscious processes, but the acquirer initially acquires the model and uses it consciously. This is a double paradox when the skill being modelled has to be unconscious, e.g. an intuitive signal.

Generalised process for acquisition

Starting with a thorough understanding and experience of using your model:

Gather information about the acquirer’s outcome, the context where they want the required results, their existing map in relation to the model to be acquired, and their learning preferences.

Where possible, modify your model to align with the acquirer’s existing map as long as the integrity and essence of your model is retained.

Design an acquisition process that includes multiple descriptions and is congruent with both the model and the exemplar’s map.

Facilitate (or make available) the acquisition process.

Utilise acquirers responses – preferably in the moment – as feedback to adapt the process of acquisition to acquirer’s model of the world and metaphors.

Test: to what degree do the acquirers get match those of the exemplar?

Some ways to present your model to an acquirer are to:

Enact the activity of each step of a sequence

Map components, their location, their functions and their relationships

Chart the flow of information and decision points

Physicalise or use non-verbal metaphor (Dance/Movement)

Tell stories and analogies

Write descriptions and give examples

Facilitating the acquisition process

It may surprise you to realise that your primary aim is not for the acquirer to acquire your model. Your model is only a means to an end. Your joint aim is for the acquirer to be able to reproduce results similar to that of the original exemplar(s).

As much as possible the acquirer needs to fully experience the model as they acquire it. So pay attention to, and calibrate whether the acquirer is replicating the model in their own mind-space and body. i.e.

Do they describe it in the correct order?

Do they gesture, look and move as specified by the model?

Do they use the same or equivalent descriptions and metaphors?

Not all components of the model will be equally important for the acquirer to acquire. Often a single piece will make a big difference. But you are unlikely to know in advance which one!

Acquiring is an iterative process. Acquirers need both big chunk information (how the model all fits together as a whole and its purpose) and small chunk information (what to do).

Different acquirers will prefer to start with different aspects of the model. For example, they might first like to get know all the bits and what they do; or how the bits fit together and relate to each other; or the order in which things happen; or where and how they can use it.

Time, repetition, multiple descriptions and feedback are useful co-teachers.

Common responses to acquisition

According to Gordon & Dawes there are 5 common ways people do not acquire a new model (assuming they want to). In effect the acquirer indicates:

I can’t get out of my present model

I can’t get into the new model

I can’t make sense of the model

I am concerned about the consequences of taking on the model

The model does not fit with who I am

One way to respectfully respond to this type of feedback is to facilitate the acquirer to self-model what is happening that means they are not acquiring the model (including how you are presenting it):

Fully acknowledge the way it is for them.

Confirm that they still want to achieve the required results.

Facilitate them to discover:

Where is there a mismatch between the existing and the new model?

What is making that mismatch possible and what is maintaining it?

Have they been in a similar situation and what did they do then?

What needs to happen to resolve it now?

What other metaphors/descriptions/representational systems will enable the acquirer to achieve the required results?

What are other circumstances where they could use the model?

What knowledge, skills or experiences need to be in place that will ease the acquirers’ acquisition process?

Notes on expert to novice acquisition

By definition, exemplars are experts while acquirers are novices (cf. Dreyfus & Dreyfus).

Your exemplar will have years of experience and lots of unconscious habitual strategies. With so much happening unconsciously, the exemplar has spare capacity to pay (conscious) attention to other things that are happening. For example, comprehending language is a completely unconscious process for a native speaker, and hence they can attend to puns, patterns, double meanings and all sorts of subtle communication that is not available to the novice second-language learner. (cf. Gregory Bateson: as behaviour is repeated it becomes ever more deeply embedded in the organism, i.e. pushed down the levels of organisation.)

An acquirer does not have the same level of experience and so the acquisition process has to act as a bridge from the novice’s way of doing things to the expert’s way of doing things. To do this you may well need to add in some extra steps that are not part of your exemplar’s model.

The NLP Spelling Strategy is a good example (Joseph O’Connor and John Seymour, Introducing NLP, 1990, p.182). This model includes a step where the acquirer spells the word they are learning backwards despite the fact expert spellers never do this. So why is it is in the strategy?

When the modellers first tried to teach the spelling strategy to poor spellers, they found that even though they learned it, they did not believe this was enough to become a good speller. So someone had the bright idea of getting them to spell the words they were learning backwards on the basis that “If you can spell the word backwards, you know spelling it forwards will be easy.” This extra ‘convincer’ step was added to make the spelling strategy more effective. (A second advantage of the backwards spelling step is that it allows the facilitator to very easily calibrate whether the acquirer is using the required visual accessing or reverting to the less efficient auditory method.)

So, you might need to add extra steps to prepare an acquirer to access a state that the exemplar switches into naturally. For example, Penny Tompkins was modelled for her ability to “notice a client’s nonverbal cues and subtle presuppositions of logic” when she is in therapy or coaching mode. Penny can instantly “clear my mind” and be in a very open and receptive state. She suggested that if someone else wanted to acquire her noticing ability but couldn’t take on her instant process, they might modify the SWISH technique so that they could temporarily move away all the stuff that is present for them until it is a dot on the horizon, and in its place bring back a “clear space” in which the client and their stuff can be situated. Although this is not how Penny does it, it would probably reproduce a similar result.

9. References:

Most NLP books are about the results of modelling projects, not about the modelling process itself. For example, the first five (pre-NLP) books by John Grinder, Richard Bandler and others were the product of their modelling. You have to read between the lines to infer the process of modelling they used.

Richard Bandler & John Grinder, The Structure of Magic vol. I, (Science and Behaviour Books, 1975)

Richard Bandler & John Grinder, Patterns of the Hypnotic Techniques of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Volume 1, (Meta Publications, Cupertino, CA, 1975)

John Grinder & Richard Bandler, The Structure of Magic vol. II (Science and Behaviour Books, 1976)

Richard Bandler, John Grinder & Virginia Satir, Changing with Families (Science and Behaviour Books, 1976)

John Grinder, Judith DeLozier & Richard Bandler, Patterns of the Hypnotic Techniques of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Volume 2 (Meta Publications, 1977)

For more information on modelling you can consult (listed in approximate chronological order):

The original and highly technical work on eliciting, designing, utilising and installing strategies is by Robert Dilts, John Grinder, Richard Bandler & Judith DeLozier, Neuro Linguistic Programming Vol 1: The Study of the Structure of Subjective Experience (1980).

Leslie Cameron-Bandler, David Gordon & Michael Lebeau wrote The Emprint Method: A Guide to Reproducing Competence in order “to provide you with tools that will enable you to identify and acquire (or transfer to others) desirable human aptitudes.” Although David Gordon now says it is really about modelling emotional competence. (1985)

Judith DeLozier & John Grinder‘s account of modelling of people who have completed interesting modelling projects can be found in Turtles All The Way Down (1987).

Also see Judith’s article ‘Mastery, New Coding, and Systemic NLP, NLP World (1995) which has a brief description of a “not knowing” state that is excellent for “intuitive modelling”.

Steve & Connirae Andreas have published numerous books on the results of their modelling including: Change Your Mind – And Keep The Change (1987), Heart Of The Mind (1989).

For a short and simple introduction to strategy elicitation, see chapter 4 of Charlotte Bretto‘s, A Framework for Excellence (1988).

Charlotte Bretto Millner, John Grinder and Sylvia Topel edited an excellent book Leaves Before the Wind: Leading Edge Applications of NLP (1991/1994) includes the results of some fascinating modelling projects.

Anthony Robbins has a very readable couple of chapters on modelling strategies in Unlimited Power (1988).

Joseph O’Connor & Brian Van der Horst aimed to update the strategies model in a three-part Anchor Point article, Neural Networks and NLP Strategies (1994)

Robert Dilts & Todd Epstein‘s Tools For Dreamers is packed with micro and macro processes for modelling with lots of examples of strategies for creativity (1991).

Robert Dilts‘ three volumes, Strategies of Genius Volumes I, II & III are the definitive work on “conceptual modelling”, especially when your exemplar is an historic figure. (Meta Publications, 1994/1995)

Robert Dilts, Modelling with NLP, provides an in-depth look at the modelling process and its applications (Meta Publications, 1998). For a short article see his Overview of Modeling in NLP (1998).

David Gordon has reissued his Modelling With NLP: An Introduction To Effective Modelling as a set of 4 CDs (1998/2004)

Michael Hall has reissued Going Meta: Advanced Modelling Using Meta-Levels (1997/2001)

Charles Faulkner & Cathryn Modrall’s article (Download PDF) Modelling an Expert; The missing piece in Knowledge Management (1998)

Wyatt Woodsmall. The Science of Advanced Behavioral Modeling (1998) and a set of 16 DVDs with the same title recorded at a 2003 training.

Robert Dilts and Judith DeLozier Encyclopaedia of NLP provides a description of many of the concepts and practices associated with modelling (NLP University Press, 2000).

James Lawley and Penny Tompkins detail a new form of modelling derived from their study of David Grove in Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling (2000).

Their website contains numerous articles on modelling: including an extensive report with video clips of Modelling Robert Dilts Modelling (2010).

John Grinder & Carmen Bostic St Clair, Whispering in the Wind (J & C Enterprises, CA, 2001) nlpwhisperinginthewind.com. Also see some short videos of John talking about modelling:

On Modelling (2008)

More about Modelling (2008)

Unconscious Assimilation (2010)

The Know Nothing State (2011)

5 Steps to Modelling Geniuses (2012)

John McWhirter article ‘Re-modelling NLP: Part Fourteen: Re-Modelling Modelling‘ (Rapport 59, 2002)

David Gordon & Graham Dawes have written Expanding Your World: Modeling the Structure of Experience(2005) with a DVD which provides an excellent introduction to modelling using their “experiential array”. There is also a wealth of information at: expandyourworld.net

Lukas Derks used “population modelling” to discover how we structure our inner social landscapes: Social Panoramas: Changing the Unconscious Landscape with NLP and Psychotherapy (Crown House, 2005). And see his article Modelling as a misleading ideology in NLP (2006).

Steve Andreas has modelled how “scope and category” creates meaning Six Blind Elephants Vols 1 and 2 (2006).

See also Steve’s article, Modeling With NLP, Rapport 46 (1999). He has also written a couple of articles in response to John Grinder & Carmen Bostic St Clair’s comments about NLP modelling: The Emperor’s New Prose (The Model Magazine, Summer 2006) and Modeling Modeling (Spring, 2006).

John Grinder & Frank Pucelik (Editors) Origins Of Neuro Linguistic Programming (2013). If you read between the lines you can discern much on how the original modelling gave rise to NLP in the early 1970’s.

Fran Burgess has made a mammoth contribution to the field by publishing The Bumper Bundle Book of Modelling (2014) and it’s sister, The Bumper Bundle Companion Workbook (2014) They are the result of 15 years observing many leading modellers first-hand. It is the first publication which provides an extensive compilation and comparison of a number of modelling methodologies used in NLP.