Background

Whatever happens during a session, excellent facilitators and therapists always seem to know where to go next. They are also able to pursue a line of questioning and to navigate elegantly through the client’s information. To find out how they do this we undertook a modelling project. Our exemplars were David Grove, Steve De Shazer, Robert Dilts, Steve Andreas (and ourselves).

We were particularly interested in contexts where the facilitator worked in a bottom-up, systemic way, i.e. instead of starting with a predetermined end point or technique, the outcome emerged out of the interaction during the process.

While this paper focusses on how vectoring works in Symbolic Modelling and other derivatives of David Grove’s work, vectoring is applicable to many situations including group work, training, chairing a meeting, interviewing, sales, research, etc.

What is a Vector?

A vector is a facilitator’s desired process outcome for the client. It involves heading in a direction (even if that is aiming to invite the client to maintain their attention in one space/time). Vectors are usually general enough to allow for several means of moving along a vector. While there are common, off-the-peg vectors which are used over and over, some vectors are ‘bespoke’ in that they are decided in the moment and are designed to fit a particular client’s circumstances. As a rule of thumb, vectors are often about 3-10 questions in length.

The purpose of using the metaphor ‘vector’ is to emphasise that the process is going or heading in a direction. In a bottom-up modelling process the ‘end’ of a vector is rarely reached. More likely a new vector is chosen part-way through. There is a strong analogy with a sailing boat tacking (see diagram).

The rest of this paper is in five parts:

- The Model

- Common Vectors used in Symbolic Modelling

- The Structure of a Vector

- Sample Vectors

- Some skills required to facilitate using Systemic Outcome Orientation

1. The Model

The diagram above represents how a facilitator-therapist-coach can use vectoring. Since it is a process which involves “circular chains of causation” (Bateson), and since circles do not have a ‘beginning’ or an ‘end’, you can arbitrarily start anywhere and follow the flow around the system.

For convenience, in the description below, we will start with the facilitator’s initial state, #2:

First Round

| #2 | The facilitator starts with a blank or empty model of the client’s model (map) of their world. |

| #3 | That means starting with no idea of the client’s desired outcome or any predetermined ‘ideal’ state (note: this includes the goal of many types of facilitation such as “integrated”, “congruent”, “mature”, “in their body”, “aligned”, etc.). |

| #4 | The facilitator chooses a desired process outcome, i.e. decides on a ‘vector’ (see below). Rather than a specific end point, the aim is for the client’s attention to ‘go somehere’ or ‘head in a direction’. An example of a common starting vector is to aim: ‘for the client to identify a desired outcome (if they have one)’. |

| #5 | The facilitator asks a question which has a high likelihood of meeting the aim in #4, e.g. they ask “And what would you like to have happen?”. |

| #6a | The client responds internally (based on their model of the world). |

| #6b | The client responds externally (verbally and nonverbally). |

Second and Subsequent Rounds

| #1 | The facilitator notices some of the client’s verbal and nonverbal responses (#6b). Penny for example is “paying attention to what the client is paying attention to” from their perspective. |

| #2 | The facilitator updates their model of the client’s model (map) of the world based on those responses. |

| #3 | The facilitator notes the client’s desired outcome statement — or the lack of one — and makes it a reference point for all future decisions. |

| #4 | The facilitator chooses a desired direction, a vector, for the next part of the process. If the facilitator is using the PRO (Problem-Remedy-Outcome) model as a guide then:

|

| #5 | The facilitator asks a question (or does some other behaviour) which has a high likelihood of meeting the chosen vector. |

| #6a | The client responds internally (based on their model of the world). |

| #6b | The client responds externally (verbally and nonverbally). |

And so on. Now the process repeats iteratively, i.e. each round builds on the previous state of the system.

Over Time

Let’s look at how the process works over time:

The facilitator’s model of the client’s model, #2, is being updated each round and therefore takes into account the entire history of their observations (#1’s). This means #2 has to be a dynamic model that includes a sense of the progression (directionality) of the client’s system.

During the course of a session a client will often identify multiple desired outcomes and/or multi-part outcomes. These will often be revised by the client during the session. Thus #3 over time contains the history of all the client’s stated desired outcomes and a sense of the progression (directionality) of those outcomes, i.e. #3 has to be a dynamic reference point.

The client’s desired content outcome, #3 may start off as a single verbal statement but over time will be elaborated into a richer description of: external behaviour; visual, auditory and body internal states, criteria for achievement, strategies for maintaining the desired outcome; metaphoric/symbolic representations; etc. etc.

Assumptions

The facilitator is always on some vector, if not chosen consciously, then chosen unconsciously. David Grove liked to quote his mentor, the sociologist Bill Rawlins, “whatever you are doing you are always up to something”.

At #1 the facilitator notices what just happened in relation to the question just asked, #5. This creates a vital feedback loop. There is information in whatever is said and done, and there is information in how that relates to the previous question. For example, what does a client have to do internally to answer a request for a desired outome with a statement of a problem?

We presuppose that a facilitator asks a question at #5 which is likely to head in the direction of their own desired vector #4. This isn’t always the case, for example, a facilitator might have the intention to model the client’s desired outcome – and actually be doing something else, like modelling their problem. However, if the facilitator’s intention is to model the problem then that is a vector in its own right. It is important to note: vectoring is not just about focussing on outcomes.

Skills Required

To use vectoring, a facilitator needs to develop certain skills, such as the ability to:

| #5 | Know the function of each question they ask and be able to deliver it with the appropriate syntax, vocal qualities and nonverbals. |

| #6 | Know what a client is likely to do internally to make sense of the question. In other words, when/where in the client’s perceptual landscape does the question likely direct their attention? |

| #1 | Be able to distinguish a client desired-outcome statement from every other kind of information presented e.g. using our REPROCess model this might be: Resources, Explanations (including meta-comments and ‘facts’), Problems, Remedies, Changes. |

| #2 | Separate their model of the client’s information from their personal model of the world (including their model of therapy). |

| #3 | Hold the client’s current desired outcome(s) in mind throughout the session. And, be able to track the history and directionality of the client’s desired outcome statements throughout and across sessions. |

| #4 | Have knowledge of, and the skill to apply a range of common vectors, and be able to devise a vector in-the-moment based on the logic in the client’s information. (See below for a list of common vectors used in Symbolic Modelling.) |

Distinctions

At any moment there are three kinds of outcome:

| #6 | The client’s desired content outcome. [Note 1] |

| #3 | The facilitator’s model of the client’s desired outcome — the facilitator’s dynamic reference point. |

| #4 | The facilitator’s desired process outcome — which is in service of #6. |

NOTE 1: This can be complicated if a client also has a process/means desired outcome, e.g. “I want to achieve X by means Y.” Commonly a client will choose a means that either won’t get them to their desired outcome or reduces their options. See: When the Remedy is the Problem.

The effectiveness of vectoring depends on:

- The isomorphism (structural similarity) of #3 and #6.

- The relevance of #4 to #3.

At times the process requires subtle modification, when:

- The client cannot state a desired outcome.

- The client is running a Self-Delusion, -Deception, -Denial pattern.

- The facilitator decides the client’s desired outcome is seriously unecological.

There are a number of other distinctions that are vital to keep in mind when working in an outcome-orientated way:

- The difference between a desired Outcome and a proposed Remedy [PRO]

- The difference between a desired outcome and an actual outcome? [Timeframe]

- Who ‘owns’ the outcome and who is it for? [Perceptual Position]

- Is it a content or process outcome? [Level]

Let’s look more closely at the ownership and the content/process distinctions.

A desired content outcome will have an owner and be for someone. There are four options:

- Client’s desired outcome for them self or someone else in their life (needed for outcome-based therapy/coaching.)

- Client’s desired outcome for the facilitator (e.g. The client plays ‘please the facilitator’).

- Facilitator’s desired content outcome for the client (needed for therapist/coaches that are ‘well-intended’; and for administrative aspects, e.g. “I want the client to pay me”).

- Facilitator’s desired content outcome for them self. (Needed in product/exemplar modelling or Clean Language Interviewing where there is no intention for change; or for exploitation where the intention is to benefit the facilitator at the expense of the client.)

A desired process outcome will be set by the facilitator (except where a sophisticated client wants to decide the process as well as the content – in which case the facilitator needs to work at a meta desired process outcome level). Different styles of facilitation will be based on the dominant timeframe of the desired process outcome:

- In the moment

- For the next several minutes (= a vector)

- For as long as it takes to do a technique (consisting of a number of vectors)

- The session

- Beyond the session

Expert facilitators are simultaneously aware of all these timeframes, although they may or may not use formal techniques (see our three-box model) .

More on Vectors

It is vital that the distinction between a client’s desired content outcome and the facilitator’s vector (desired process outcome) is clear to the facilitator. Should this be forgotten there is an increased likelihood that the facilitator’s desired content outcome becomes involved, and the process becomes less and less clean.

A key concept is ‘nested or simultaneous vectors’. For example, in a recent demonstration, Penny’s initial vector was “For the client to identify a desired outcome” (vector A). Since this wasn’t immediately forthcoming, Penny kept this vector open while heading off on another vector which was “For the client to develop a perceptual landscape for their current state” (vector B). As Penny facilitated the client to locate a few symbols a current-state inner landscape began to take shape. When, at her tenth question, Penny again asked ”And what would you like to have happen?”, the client answered with a desired outcome statement. This ended vector A. Vector B was left open and temporarily set aside in pursuit of a new vector “For the client to develop their desired outcome perception” (vector C). This continued for half a dozen questions until a problem with the desired outcome became apparent, which set Penny off on a new vector D (attend to the problem) …

TOTEs

There is a similarity between a vector and a TOTE. The T.O.T.E. (Test, Operate, Test, Exit) model is an iterative problem-solving strategy based on feedback loops, devsied by George A. Miller, Eugene Galanter, and Karl Pribram (Plans and the Structure of Behavior, 1960). If you are familiar with TOTEs and are able to apply them in the moment during a client session you probably won’t need the notion of a vector. However, if you’ve never quite been able to apply TOTEs, the vector metaphor might be more to your liking. One advantage of the vector metaphor is that it is more embodied than the TOTE — imagine sailing boats making progress by tacking rather than abstract computer algorithms.

We’ve always found it strange that although a Goal is part of the model it is not included in the acronym TOTE. By contrast, a vector by definition includes a direction. Another distinction between the two is that a vector is about heading in a direction, whereas a TOTE is about achieving an end-state (from which you Exit). In the ever-changing process called therapy, if you are not using a technique, getting to the ‘end’ of a vector is an exception rather than the rule.

To conclude

At every moment vectoring requires the facilitator to hold in mind both a client-content and a facilitator-process desired outcome. Because the client’s desired content outcome can change over time, and because except in the simplest of cases the client can’t go straight from where they are to their goal, the facilitator needs to regard the client’s desired outcomes as a series of dynamic reference points.

In a top-down, technique-based approach the facilitator has an idea of where the whole process is going and their job is to guide the client towards that.

In a bottom-up vectoring approach the end result is not known until the client gets there. Therefore the facilitator needs to continually be prepared to modify the process direction in light of each new piece of information. In setting a direction in the moment the process heads along a vector for a short time before heading off on the next vector. The overall direction of the session thus becomes the sum of all of the vectors and the length of time each vector is maintained.

Lastly, in the above we have focused on desired outcome orientation. Another important component is actual outcome orientation. As a rule, the focus of the orientation will over time alternate between desired and actual outcomes.

Source material of our exemplars:

Steve Andreas, a video of Steve using The Forgiveness Pattern (CD set).

Robert Dilts, the transcripts and videos of the Northern School of NLP workshop (2006) examples available in Modelling Robert Dilts Modelling.

Steve De Shazer, the transcripts in Words Were Originally Magic (1994).

David Grove, many many hours of observation and the all the transcripts, audio and video tapes listed in his Bibliography of Publications.

Acknowledgements

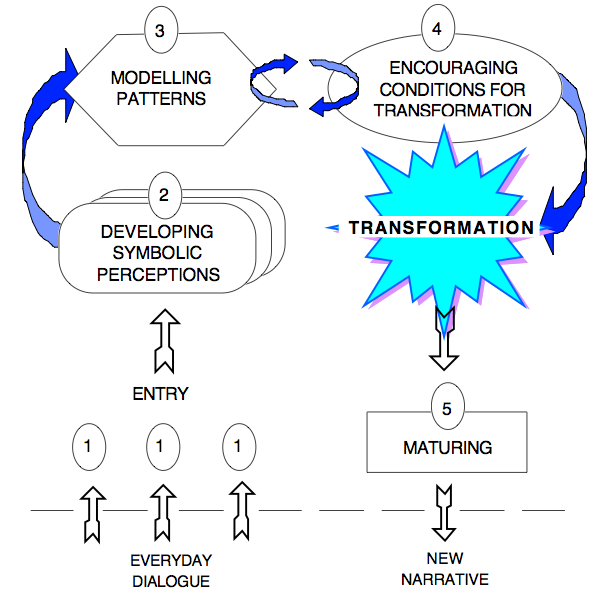

2. Common Vectors in Symbolic Modelling

Common Vectors used in a Symbolic Modelling Change Process ‘Stages 1-5’ below refer to The Five Stage Process described in detail in Metaphors in Mind.

STAGE 1 ENTRY

Clean start (set up)*

Identify a desied Ouctome statement *

From a map (drawing) into space

STAGE 2 DEVELOP SYMBOLIC PERCEPTIONS

Develop a desired Outcome Landscape *

Identify Outcome achievement evidence / criteria

Select from multiple desired Outcomes

Develop a landscape which includes Resource’s, Explanations, Problems and Remedy’s:

- Developing a Resource

- Sourcing a Resource

- Finding what’s problematic about the Problem

- Developing a Remedy

General Developing Vectors:

- Feeling to metaphor

- Embodying a perception / Encouraging psychoactivity

- Going live

STAGE 3 MODEL PATTERNS

Model the patterns and logic within and across perceptions:

- Explore the effects/ecology of desired Outcome on the wider system *

- Identify a sequence

- Elicit causality

- Test logic of Explanations

- When the Remedy is the Problem

- Incompatible desired outcomes (e.g. Problem binds)

STAGE 4 ENCOURAGE CONDITIONS FOR CHANGE

Make use of the 7 Approaches:

- Concentrating attention

- Attending to wholes

- Broaden attention

- Lengthening Attention

- Identifying conditions necessary for change *

- Introducing Resources

- Attending to Adjacency

STAGE 5 MATURE CHANGES

When a Change occurs, mature it *

Evaluate progress by reviewing against actual outcomes

Clean finish *

Assignments

Note:

Because Symbolic Modelling is a modelling-based process, none of the vectors used are about the facilitator having an outcome to make a change happen.

3. The Structure of a Vector

Supplementary notes following The Developing Group, 2 August 2008

There are two types of vector:

From a … To a …

From … Towards …

[Thanks to Marion Way for this idea and see also John McWhirter’s FROM-TO-IN model in ‘Re-Modelling NLP, Parts 1-14’, Rapport, issues 43-59 (1998-2003).]

Examples of generalised vectors are given in the next section

‘From a … To a …’ vectors have a more or less definite end point. They are usually used to facilitate the client to ‘Identify […]’ where […] is a particular aspect of their experience, e.g. a metaphor, a desired outcome statement, evidence or criteria for how they know something, etc.

The classic ‘From a … To a …’ vector was devised by David Grove in the 1980’s and became known as ‘From a feeling to a metaphor’. This vector facilitates the client to ‘Identify a metaphor/symbol for a feeling or other sensation’ (see section 4 ‘Sample Vectors’). It has all the hallmarks:

- It has a starting point: from an aspect of the client’s current experience, in this case a feeling.

- It has an aim, an end point: for the client to represent the sensations of a feeling symbolically.

- It has a means: by which (usully through a series of steps) the client is offered the opportunity to get to the end point. In this case, by locating the feeling, then identifying a number of sensory attributes of the feeling, and then using the attributes to invite the client to convert or translate those into a metaphor or symbol.

Another common ‘From a … To a …’ vector is the ‘From a Problem/Remedy to a desired Ouctome’ by using the PRO model.

‘From … Towards …’ vectors have no definite end point. The facilitator is always having to decide if, in the moment: (a) the client has experienced “enough” for the vector to be considered completed; or (b) the client has just said or done something that seems even more salient.

‘Develop …’ is the most commonly used class of vector of this type. The typical ‘From … Towards …’ vector is exemplified when the client is facilitated to ‘Develop a desired Outcome perception’. It comprises:

- A start from a statement of the client’s desired Outcome.

- An aim to move in a direction toward the client embodying a 3D psychoactive perception of their desired outcome.

- A means: by answering developing questions (which hold time still) the client is likely to be able to elaborate the form, location, function and the relationships between the key symbols that comprise their desired outcome.

How much and for how long the client is facilitated to maintain their attention on a single desired outcome perception depends on a whole raft of factors. The facilitator will likley take into account things like the:

- Logic of the content the client’s desired outcome.

- Response of the client to their own perception and words

- Level of self-awareness of the client

- Ease/difficult with which the client is able to create a desired outcome perception

- Time available for the facilitation

- Kind of relationship and level of rapport between client and facilitator

“All forms of tampering with human beings, getting at them, shaping them against their will to your own pattern, all thought control and conditioning is, therefore, a denial of that in men which makes them men and their values ultimate.” Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty (1958) quoted in The Guardian Weekend Magazine, August 2, 2008, p. 65. |

Vector names

Remember, the following examples of common vectors are abstract generalities. They are for illustrative purposes. Vectors are what actually happen during actual client sessions (or other interactions). In this respect every vector is unique. A vector is the direction in which:

the facilitator thinks they are heading,

or

an observer thinks the process is heading (or has headed, if the analysis is done after the session took place).

Although vectors are defined by their From-To(ward) structure, as a shorthand common vectors have acquired names. For consistency and to show that vectors are active processes, we think these names should (as a rule) be of the form:

Verb + Noun Phrase

e.g.

IDENTIFY a desired Outcome

IDENTIFY evidence for a desired Outcome happening

IDENTIFY a metaphor from a feeling / nonverbal / concept

IDENTIFY what is problematic

IDENTIFY an Explanation

IDENTIFY a Child Within

DEVELOP a desired Outcome perception

DEVELOP a Resource perception

DEVELOP a Remedy perception

DEVELOP a Problem perception

EXPLORE the effects of a desired Outcome happening

ELICIT a sequence

MATURE a change

SOURCE a Resource

TEST the robustness of state / perception

We define the most common vector-verbs as:

VECTOR DEFINITIONS/METAPHORS

| Stage* | Vector | Definition |

| 1 | Identify | Make known, put a name to, establish, make out, discern, distinguish |

| 1 | Elicit | Draw out, extract, bring out, bring into the foreground |

| 2 | Develop | Elaborate, give form to, bring forth |

2 | Select | Pick out from a number of, single out, opt for, decide on, settle on |

| 3 | Explore | Investigate, find out what’s there, look into, search |

| 3 | Test | Trial, assess, (re)examine, check out |

| 4 | Source | Find: origin, instigator or ‘from whence it came’, root, beginning, genesis |

| 4 | Encourage | Prompt, foster, cultivate |

| 5 | Mature | Evolve, develop, extend, follow effects, ripen, bring to fruition, grow up |

| 5 | Evaluate | Assess, compare/contrast, weigh up, rate, appraise |

* The stage where this class of vector would typically be applied in The Five Stage Process (described in Metaphors in Mind).

4. Sample Vectors

Facilitate the client to …

IDENTIFY a desired Outcome

| From: | A Problem/Remedy statement |

| To: | A desired Outcome statement |

| By: | Using the PRO model:

|

IDENTIFY evidence for a desired Outcome happening

| From: | A (general) desired Outcome statement |

| To: | Sensory (VAK) description that will let the client know that desired Outcome is happening or has happened. |

| By: | And how will you know [desired Outcome]? +Developing questions to elaborate on the sensory-based evidence:

|

IDENTIFY evidence for an Explanation

| From: | An explanatory statement (e.g. a reason, belief) |

| To: | Sensory (VAK) description that lets the client know their own experience. |

| By: | And how do you know [Explanation]? + Developing questions to elaborate on the sensory-based evidence:

|

IDENTIFY a Metaphor from a Feeling

| From: | A feeling |

| To: | A metaphor or symbol |

| By: | Locate the feeling x 3:

Then identify attributes:

Then ask for metaphor:

|

IDENTIFY a metaphor from a nonverbal

| From: | A nonverbal (e.g. gaze, gesture, sound) |

| To: | A metaphor or symbol |

| By: | Bring nonverbal into awareness using one or more of:

If necessary, locate the symbol x 3:

Then identify attributes:

Then ask for metaphor:

|

IDENTIFY a metaphor from a concept

| From: | An abstract conceptual word |

| To: | A metaphor or symbol |

| By: | Identify attributes:

If necessary, locate the symbol x 3:

Then ask for metaphor:

|

IDENTIFY what’s problematic

| From: | A present state/Problem/Remedy statement |

| To: | An explanation of how this is problematic for the client |

| By: | [ADDED 15 Oct 2014] This is not a common or easy vector to define. So, rather than give a list of ‘standard’ questions, an example transcript will hopefully capture the essence of this vector. The challenge for the facilitator is to NOT assume that a situation is problematic even when the client’s way of talking implies a problem. Real life situations are not in and of themselves ‘problems’. It takes a human being to experience the situation as a problem. We are aiming to identify what specifically is problematic for this client (without asking that strongly leading question – although we have been known to ask it as a last resort). C: My children misbehave. [This is what is problematic for this particular client in this particular context, so now it is time to switch to a new vector, e.g IDENTIFY a desired Outcome:] F: And when you feel misunderstand, and you feel sick, what would you like to have happen? |

IDENTIFY a Child Within

| From: | A Personified symbol |

| To: | A Child Within |

| By: | Developing the personified symbol:

Here we are facilitaing the client to identfy a ChildWithin’s body that can do something (e.g. feet that can run, hands that can hold, a voice that can speak etc.). |

DEVELOP Resource/Problem/Remedy/desired Outcome perception

| From: | A statement of a Resource or Problem or Remedy or desired Outcome |

| Toward: | A 3D perception of the form, location, function and the relationships between key symbols that comprise a Resource/Problem/Remedy/desired Outcome. |

| By: | Identifying and elaborating on the: Form and function (name):

Location (address):

Relationships between symbols:

|

EXPLORE the effects of achieving a desired Outcome

| From: | A (developed) desired Outcome |

| Toward: | A new or evolved landscape |

| By: | Identifying consequences:

Developing the effects:

|

ELICIT a sequence

| From: | An event |

| Toward: | A sequence of events |

| By: | Identifying a coherent sequence of sub-events:

|

MATURE a change

| From: | A change |

| Toward: | A new or evolved landscape |

| By: | Evolving the change:

Developing the changed form or function (name):

Identifying a changed location (address):

Spreading the change:

|

SOURCE a Resource

| From: | A description of a Resource |

| Toward: | The source of the Resource |

| By: | Iteratively using:

When client’s nonverbals indicate they have touched a purer / stronger / sacred state, develop the new symbol so that the client is embodying the new resource:

|

5. Skills Required

Some skills required to facilitate using Systemic Outcome Orientation

General in-the-moment abilities:

- Recognise a client’s desired outcome (CDO) statement

- Distinguish CDO’s from all other types of description (especially Remedies)

- Recognise when you do not have a CDO

- Recognise multi-part, multi-level, multi-type CDO statements

- Maintain a relevancy check in relation to the CDO

General across-time abilities:

- Hold the current CDO in mind throughout the session

- Model the structure/organisation of CDOs

- Notice patterns in CDOs

- Muse on the logic of the CDOs (e.g. presupposition, inherent logic, causal links etc.)

- Track changes to a CDO and model their dynamics

Abilities to facilitate a client to:

- Identity a CDO.

- If client cannot identify a CDO, work within logic of their information until they can

- Elaborate their CDO statement (into an embodied perception)

- Identify evidence criteria for when their CDO is happening or has happened

- Relate their CDO to other aspects of their experience

- Explore effects of the CDO happening (ecology of self, other, system)

- Explore and select from multiple CDOs

- Test the robustness of their CDO.

- Direct attention to salient aspects of their experience and orientate toward their CDO

- Utilise when they appear to do their desired outcome

- Review progress toward a previously defined CDO (i.e compare actual with desired)

Relationship with self

- Know own model of world, especially values, beliefs, preferences and be able to separate them from the client’s.

- Know when client’s desired outcome is incompatible with your own values – refuse or renegotiate the contract.

- Recognise own reactions and utilise or set aside as appropriate.

Recognise and manage your need to rescue/help/solve their problem/make something happen/achieve a result/know what’s best for them/tell them what you would do if you were them/etc.

First presented at The Developing Group, 2 October 2008.