1. BACKGROUND

- “I need scaffolding”

- Stand-alone coaching process

- Features

- Applications

Sources

2. THE PROCESS

- Terminology and format of diagrams

- Overview

What is a change?

Stage 1 – Identify a desired outcome

- Purpose of Stage 1

- What is a desired outcome?

- Desired outcomes are not WFOs, SMART or BHAGs

- Timeframes: the 3-Box Model

- What happens to problems?

- What is a remedy?

The PRO model

Stage 2 – Develop a desired outcome landscape

Stage 3 – Explore effects

Stage 4 – Identify necessary conditions

Stage 5 – Mature changes

3. ANYTHING ELSE?

- When nothing changes

- Developing resources

- When ACFC is not enough

- Achieving what you want

Concluding remarks

Footnotes

1. BACKGROUND

"I need scaffolding"

“But I need something,” a desperate student pleaded. “I need something, some, some, … scaffolding to help me build my model.” “OK”, James replied “And then what happens?”. “Once my building is in place I can take down the scaffolding and use my own model to do this stuff.”

This was the moment that we decided to devise an intermediate step for students wanting to learn how to use the 5-Stage Symbolic Modelling Process described in Metaphors in Mind. Symbolic Modelling is a generalised, bottom-up approach used to cleanly facilitate clients to self-model – from their in-the-moment experience to the patterns of their life. And as they do, organic changes occur which fit with the whole of their system.

Up to this point we had resisted producing a more procedural model because of the incongruence of teaching students to model bottom-up by giving them a top-down process! However we now had enough feedback that for some students the lack of structure was triggering responses which were inhibiting their ability to learn. The plea for scaffolding was the final straw. But what form should that intermediate step take?

We were aware of the downside of designing scaffolding. Once it is in place the path of least resistance is to leave it there. So we aimed to provide just enough structure for students to become effective at Symbolic Modelling while still giving them plenty of opportunity to acquire an expertise in bottom-up modelling.

Although we set out to provide ‘scaffolding’ we ended up with a process that acts like a ‘frame’ – or rather a series of interconnected frames. Rather than having to remove the scaffolding so carefully erected, we preferred the metaphor of a framework to which a variety of veneers and embellishments could be added. Hence A Framework for Change. That was in 2002. In the intervening years we have learned a lot about how people use the model with some surprisingly valuable side effects. We continued to tinker with the model until 2010 when it was renamed, A Clean Framework for Change (ACFC) – and that is the version described below.

Note: Since 2011 we have taught a simplified form of the 5-Stage Process in Metaphors in Mind, called Symbolic Modelling Lite – published as Symbolic Modelling: Emergent Change though Metaphor and Clean Language.

Stand-alone coaching process

We originally designed ACFC as a way for students to acquire the abilities required to be an effective symbolic modeller. It was not until we started using ACFC that we realised it was a fully-formed stand-alone coaching process. We reviewed several well-known coaching models and it was clear that while ACFC had overlaps and was compatible with many of them, it offered something different. The key distinguishing features are:

- The Clean Language of David Grove

- A modelling-based methodology

- Attending to metaphors generated by the client (an optional and highly recommended add-on).

We called the process A Clean Framework because the facilitator needs to commit to staying ‘clean’. This means using Clean Language at every stage. With Clean Language the precise wording of each question is given – the facilitator only need fill in the appropriate client words to complete the question. Furthermore, we have identified which Clean Language questions asked at each stage will likley achieve the maximum effect with the minimum of effort.

Although ACFC is primarily used for coaching, the facilitator is not a ‘change agent’ since they are not attempting to change the client nor their inner landscape. This is because ACFC is a modelling methodology in which change is a by-product. You will notice there is not a stage where change happens. Instead we recognise the client’s desire for something to be different as the starting point, the motivation and the contract for the session. Their desire for change does not need bolstering by our desire for them to change. In fact, the imposition of our desire into their process is often counter-productive.

Despite the specificity of the questions and the lack of an intention to change there is plenty of room for the facilitator to play a significant but different role to that of a traditional coach. Instead of putting effort into problem solving or thinking of ‘powerful’ questions or helping to motivate the client, the ACFC facilitator works with and within the client’s model of the world.

If you are an experienced coach or therapist you will probably be saying to yourself ‘I do that already’. And you may, but not to the extent required by ACFC. Over the last 15 years we have trained coaches, therapists, counsellors and facilitators from just about every school on the planet and what we have observed is that it is not until you use Symbolic Modelling, and more important, are facilitated by an experienced symbolic modeller, that you will realise the difference – and that difference makes a profound difference. We are not saying ACFC is always more effective or more efficient than other models, but we do say it can often get to patterns of internal behaviour that are rarely accessed by other means.

To be clear, staying clean and maintaining a modeller’s mind require a lot of a facilitator. These are not common ways of thinking, especially if you have been previously trained in problem-solving approaches. Facilitators have to work with approaches that are congruent with who they are. For some, ACFC doesn’t fit but those who persevere discover, as one of our students remarked, “it is not just another tool for the tool box, it is a whole new toolbox”.

Like all approaches, ACFC is not suitable for all clients in all circumstances. We acknowledge that there are occasions,rare in coaching, where an ACFC approach may not be appropriate. However, since we do not know in advance which are the few clients whose make-up is not compatible with this approach, we almost always start out with ACFC and make suitable adjustments based on the client’s responses (see the section: Anything Else?). The more a facilitator can adapt to clients’ unique ways of being in the world, the greater the range of clients they can work with using ACFC.

Features

A Clean Framework for Change is a model with a series of stages. It is designed to support a facilitator to invite a client to attend to aspects of the self so that he or she self-model’s their desired outcome, the effects of that happening and the conditions under which the desired outcome would happen naturally. And when a change spontaneously occurs, the client is facilitated to self-model the effects of that change having happened.

A feature of a clean approach, and what distinguished it from other approaches, is that the facilitator can only refer to what the client describes – both within their metaphor landscape and outside in ‘real life’. They cannot introduce any content that is not already present in the client’s inner world.

ACFC’s key features include:

- Based on David Grove’s ‘clean’ approach

- Client-information centred

- Non-directive at the level of content

- Outcome orientated

- Process orientated

- Accepting of ‘what is’

- Utilises ‘what ever happens’

- Trusts in the ‘wisdom of the system’

- Is a modelling process that facilitates the client to self-model

- Does not have an intention to change the client.

- Can be conducted ‘content-free’ (i.e. in metaphor so the facilitator has no idea of the ‘real life’ situation)

- Can be used over time periods of a few minutes to a series of sessions

- Equally effective when used with those who prefer to work ‘cognitively’ as well as with those who make more conscious use of their emotions and their body.

In the session there is only ‘now’. All desired outcomes are constructs of a human mind. As are all expected effects. And while the relationship between the facilitator and client is an important part of the process, more important is the relationship between the client and their constructs. In ACFC we want the facilitator-client relationship to drop into the background and the client-and-their-construct relationship to come to the fore. When this happens we say the client is self-modelling.

Applications

Primarily designed for one-to-one facilitated change work and in particular as a model for coaching, ACFC is an efficient way to start most change processes including many psychotherapies that recognise the importance of goals or objectives. Using the Problem-Remedy-Outcome (PRO) model of Stage 1 and the developing questions of Stage 2 is a remarkably elegant way to directa client to attend to the part of their experience that knows how they would like himself or herself and the world to be.

However ACFC has a much wider applicability. It has been used effectively in contexts that last anything from a few minutes to a few sessions. It has formed the basis of:

- The Weight Watchers’ One-Minute Motivation Programme

- Business planning processes

- Conflict resolution

- Gathering user requirements and customer specifications.

Sources

ACFC has not emerged out of thin air. Rather it is a product of a very fertile soil. That soil originated from a number of sources, including:

David Grove – primarily we constructed the process around Grove’s Clean Language, and based it on his way of working with clients’ internal experience, and in particular their metaphors. [See our Metaphors in Mind]

NLP (Neuro-Linguistic programming) – especially: the notion of modelling; the NLP presuppositions that “people aren’t broken so they don’t need fixing” and “people have all the resources they need”; and the ideas behind a number of models designed or articulated by Robert Dilts and Todd Epstein, e.g. Well-formed outcomes, TOTE, ecology, SCORE, Pathway to Health. [See: NLP Encyclopedia]

Robert Fritz – in particular his insights into the nature of desired outcomes and current reality. [See: The Path of Least Resistance and Creating]

Gregory Bateson for how to think systemically while working with and being part of a complex adaptive system. [See: Steps to and Ecology of Mind]

Steve de Shazier and Insoo Kim Berg and their Solution Focus Therapy for how to continually orientate questions to the client’s resources, changes and exceptions. [See: Words were Once Magic]

Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing process, for providing evidence that what the client does is the key to effective change-work, and for the value of the client keeping their attention on a single experience thereby allowing its form to become apparent and named. [See: Focusing]

In addition, sitting in the background of ACFC is our knowledge of self-organising systems, evolutionary dynamics and cognitive linguistics. Full references to the sources of these ideas can be found in the extensive bibliography in Metaphors in Mind and more recently in an article written with Judy Rees, Theoretical Underpinnings of Symbolic Modelling [1].

2. THE PROCESS

Terminology and format of diagrams

When using the word ‘outcome’ we make a number of distinctions:

Desired outcomes refer to that universal human impulse of wanting to create something new in the world or to develop our self.

Desired outcomes are distinguished from the desire to remedy or solve problems (defined below in Stage 1).

Desired outcomes have yet to happen while actual outcomes have already happened or what is are happening now.

A desired outcome becomes an actual outcome once it has been achieved or experienced. Notice that even if the desired outcome is not achieved, something always happens and therefore there is always an outcome.

And there are always effects or consequences of an outcome. In the case of a desired outcome the effects are what’s expected or anticipated and may or may not happen. Whereas once an outcome has actually happened there will always be further effects – some intended and often many unexpected and surprising.

In the diagrams below we have used a consistent format to indicate different aspects of the process:

- The purpose of each stage is indicated by the title of that stage.

- The questions in the diagrams show you what to do.

- Arrows show the usual flow though the process.

- We use colours to distinguish between different classes of experience as described by a client:

Red = a Problem

Purple = a Remedy

Blue = a desired Outcome

Green = a condition necessary for change

Orange = a change

Our diagrams are only one way to conceptualise ACFC, others have devised their own versions.

Overview

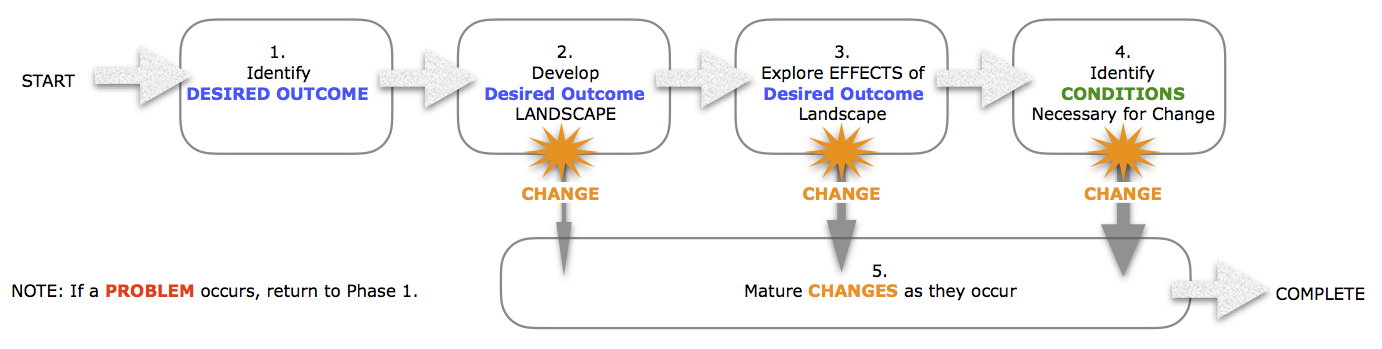

Before we go into the details of each stage we will look at the process as a whole and the relationship between the five stages shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The five stages are provided as a framework to guide the facilitator while accompanying a client on their unique journey of self-evolution. Your knowledge about where they are in the process will inform your choice of which clean question to ask and what to ask it of.

While we have presented the five stages sequentially the process is not linear, the transition between stages is necessarily ill-defined because so much depends on the individual circumstances happening in the moment. And, change is unpredictable, iterative, fuzzy and emergent. Stage 1 does not happen just at the beginning. The client may shift their desired outcome once or several times during a session. Unforeseen problems can reveal themselves at any time. Therefore the client will likely be taken through the Stage-1 process several times during a session.

Similarly, self-modelling is a recursive process which frequently produces spontaneous and surprising changes. Whether this happens during Stages 2, 3 or 4 no one can say. As soon as a change occurs, the client is immediately invited to mature the change and the process moves to Stage 5. Like all other stages, maturing is not a one-time event. It will likely to involve a series of iterations as the client’s landscape metamorphoses and a new organisation emerges.

In its simplest terms the ‘formula’ for using ACFC is:

Start at the beginning and go through the stages in order.

Use the client’s evolving desired outcome throughout the session as a dynamic reference for where to go next.

Acknowledge and note any problems as they arise and apply the Problem-Remedy-Outcome model.

Continue until a change spontaneously occurs, then immediately mature the change and see what effect it has on the rest of the landscape, in particular any problems identified previously.

Stop when a new landscape emerges which is agreeable to the client and can handle previously identified problems – or you run out of time.

To get a sense of the nature of the process note the metaphors we used in Figure 1:

Identify

Develop

Explore

Identify

Mature

A subtle yet vital aspect of ACFC is the perspective the facilitator takes in relation to the client and their internal landscape — the trialogue as David Grove called it. The facilitator sets aside their own perceptions and commits to working exclusively with and within the client’s metaphor landscape. ACFC is a guide for the facilitator and yet the purpose of each stage (as highlighted by its title) is what the client does. The facilitator’s role is to facilitate the client to self-model — to identify, develop, explore and mature — how their inner world works.

Holding this perspective requires the facilitator to split their attention in an unusual way. The facilitator is both tracking the progress of the client’s process from an outside perspective and simultaneously tracking the client’s attention from their internal perspective.[2]

What is a change?

Before we journey through the stages, let’s pause and consider what we mean by ‘a change’. In Metaphors in Mind we said:

At some point the client experiences a change. Given how little is known about the process of how people change, probably the most accurate description of this is: ‘and then a miracle occurs’. Thereafter the aim of the process itself changes—from seeking change, to seeking to preserve, stabilise and maintain the changes. Eventually the new becomes old as the client continues their journey of personal development. (p. 40)

That was in 2000, and all the revelations of neuroscience in the last ten years have only served to strengthen our opinion. How exciting to be working with a process that can’t be fully defined, can’t be predicted and can’t be controlled – makes you think of Mother Nature, doesn’t it?

The first thing to notice is that ‘change’ is not a stage in the process. It is not something that you do, it is an effect that can happen anywhere or at anytime. The three orange starbursts in the overview diagram (Figure 1) signify a change happening at Stage 2 or 3 or 4. We have attempted to show the likelihood of a change occurring at each stage by the thickness of the arrows leading from the starbursts to Stage 5.

Changes may be surprising but they are not random. ACFC is a cumulative process. As a general rule the more a client is facilitated to self-model cleanly, the more likely they will experience something shift.

Only though its effects can the significance of a change be known. Development rarely happens in a road-to-Damascus moment, more often it involves a series of incremental and iterative changes. When a complex adaptive system changes there will always be unexpected effects. The serendipitous nature (or not) of an event cannot be predicted in advance, it can only be known after the event.[3] This is why immediately a change is detected we mature it to find out what happens over time and to the rest of the landscape.

Often a small change will lead to another change, which will result in another change, and so on in a cascade or contagion. In this way even apparently small changes can set in train a process that ends with major effects. This is such an unpredictable process that we recommend you give up trying to second guess when the client’s system will experience a change and what the effects of that change will be. Instead, we put our attention on encouraging the conditions which offer the opportunity for change; on noticing the cues that indicate something is changing; on responding to those cues by maturing the change; and then sit back and marvel at what unfolds.

With enough experience of clients and their metaphor landscape changing you can develop an intuitive signal for when the client’s system is on the edge of, or has the potential for a creative change. When you get that signal, other than inviting the client’s attention to stay where it is, your job is to do as little as possible.

We will now look at the stages of the journey in more detail.

Stage 1 - Identify a desired outcome

Purpose of Stage 1

All change processes have to start somewhere. How the client starts and how the facilitator starts can have a major effect on the direction the remainder of the session takes. David Grove trained us to pay particular attention to a client’s first words.[4] In ACFC we start by asking the client what they would like to have happen. While commonly clients respond with a statement. it could be a sound, a gesture, a drawing or anything else that represents how the client would like themselves or the world to be.

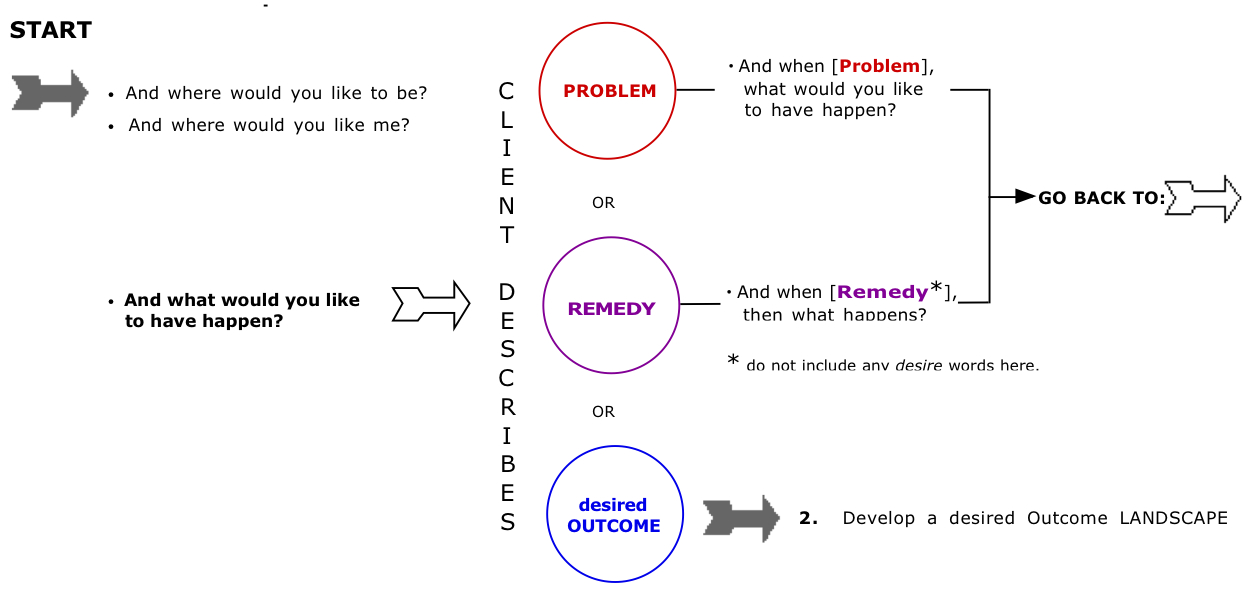

We did not know of any method that explained how to facilitate a client so that they identified a desired outcome in which they were not expected to meet any criteria. So we self-modelled how we did it cleanly. The result was our Problem-Remedy-Outcome (PRO) Model.[5]

The key to using this model is to be able to instantly recognise throughout the processwhen the client is attending to a current Problem, a proposed Remedy, or a desired Outcome. To do this you have to model what kind of experience the client is attending to from their perspective. This sounds simple, and it is, but it is not something even highly experienced therapists, coaches and facilitators do naturally. If you want to master PRO you will need to set aside many of your presuppositions, all mind-reading and apply yourself diligently to only work with the descriptions used by the client.

The PRO model is a two-stage process: (1) identify whether the client is describing a Problem, a Remedy or a desire Outcome; and (2) respond with the appropriate Clean Language question which invites them to attend to a desired outcome. We’ll say more about this below.

We will now examine the nature of desired outcomes, and the experiential and linguistic differences with problems and remedies.

What is a desired outcome?

Desired outcomes describe how the client would like the world to be, or how they would like to be in the world. They differ from remedies because they are not a solution to a problem. When a pilot sets out to fly a plane from A to B they know they may encounter problems along the way, but their aim is not to solve problems, it is to arrive safely – and that’s a desired outcome.

The most common way of communicating our desires to ourselves and others is through statements. However, a desired outcome is more than the words in a statement, it is a way of relating to the world.

A desired outcome statement has the following distinguishing features:

- It contains a desire word – a want, need, would like, etc. that indicates an impulse for a new situation, state or behaviour, i.e. for the world to be different in a way that adds something

- The outcome has not yet happened, i.e. it is in the future.

- It does not overtly reference a problem.

The last distinction is important. Even though you may think you can guess the client’s problem, unless it is stated, you will be guessing. If a client says “I would like to be more confident” you might assume their problem is ‘low self-esteem’ (or something similar). But that would be your assumption since the client has not given the slightest indication that the metaphors of ‘esteem’ and ‘low’ are part of the way they imagine themselves. Even if you assumed they suffered from ‘a lack of confidence’ you would still be presumptuous. Just because the client says they want ‘more’ confidence does not necessarily mean they ‘lack’ anything or that the amount of confidence they currently have is a problem for them. If the world record holder for 100m and 200m Usain Bolt says he wants to run faster, it doesn’t mean he has a problem; he may simply want to improve what he already does.

Secondly, even if the client experiences a problem they may not conceive of it through the metaphor of ‘lack’. For them the problem may be ‘scared’ or ‘overwhelmed’ or ‘feeling like a door mouse’ or … a thousand other possibilities, many of which you would never guess. It is much easier to stay clean, stick with the client’s words and to refrain from guessing and assuming.

It takes time and mental effort to try and second-guess a client’s problem – assuming they have one. With ACFC and Symbolic Modelling it’s more effective to put your attention on what they have told you and marvel at just how much information is contained in those few words placed in that particular order and said (or written) in that precise manner. To paraphrase Charles Faulkner, there is a world within each word.[6] We are aiming for the client to attend to that world. That world will be an inner, private, first-person world since at this stage their desired outcome only exists in their imagination.[7]

Desired outcomes are not WFOs, SMART or BHAGs

While the Well-Formed Outcomes of NLP, SMART goals and Big Hairy Audacious Goals have similarities to our definition of desired outcome, there is an important difference. They require the facilitator to decide whether what the client has said is ‘specific’, ‘measurable’ ‘realistic’, ‘achievable’ or ‘audacious’ enough. This will inevitably involve the facilitator’s personal preferences since what they may think as specific, measurable, realistic, achievable and audacious may vary enormously from what anyone else or their client thinks.

In ACFC the facilitator is still making a judgement but instead of a personal preference it is judgement sourced in the client’s words and based on the criteria: does the sentence contains a desire word, is it set in the future and does it notreference a problem?

We are not saying our definition is better than other models, we are saying it is different and simpler, and consequently gets different results. If being audacious or specific etc. does not suit the client, what are they to do? In this situation many facilitators will (unintentionally) help the client change their language to fit the facilitator’s preferences. And many clients comply – or at least appear to comply. Basically, the aim of ACFC is to leave the client as much freedom as possible to determine their own criteria for what constitutes their personal desired outcome.

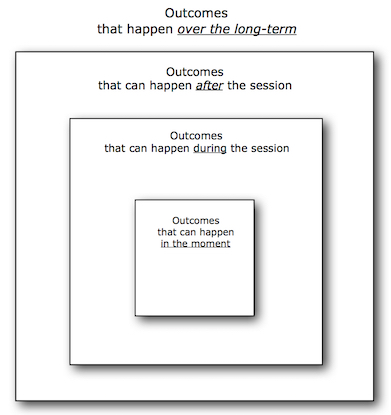

Timeframes: The 3-Box Model

Our aim is to facilitate the client to identify a desired outcome and often as the session unfolds other related outcomes make an appearance. The 3-box outcome model is a way to track shifts in a client’s desired outcome in relation to the time frame when the outcome can happen:

- Over the long term

- After the session

- During the session

- In the moment

Commonly the initial timeframe of the client’s outcome will be on what they want to have happen after the session and beyond. As a session progresses the client will often describe their desired outcomes with shorter and shorter time frame, until they are working on something that can happen ‘live’ in the moment.

For example:

| CLIENT’S DESIRED OUTCOME | TIME FRAME |

| I want to have a happy life. | Over the long term |

| I would like to get married some day. | After the session |

| I want to know how to take the first step. | During the session |

| I’m now ready to make a decision. | In the moment |

Encouraging desired outcomes that have shorter time frames does not negate the original longer-term outcome, it simply shifts attention. The shorter-timeframe desired outcomes can be thought of as nested inside longer-term desires like Russian Dolls. For simplicity Figure 2 shows smaller boxes nested within larger boxes.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Just as we are not problem-focussed, neither are we solution-focussed. By our definition a solution retains a relationship with the problem it is attempting to solve, and therefore remains indirectly problem-focussed.

But neither are we goal or outcome focussed in the commonly used meaning of those terms. Rather the approach ACFC adopts is outcome orientated. There is a constant orientation towards, and reference to the client’s desired outcome. We consider a desired outcome to be a dynamic reference point because as the session progresses the formulation and emphasis of the client’s desires often change. The facilitator needs to track these changes.

What happens to Problems?

While ACFC is an outcome-orientated approach, it is not anti-problem and it doesn’t only go for the ‘positive’ – quite the opposite. We think problems play a fantastically important role in the development of people’s lives. We also think that problems get far too much press. In everyday conversation people regularly spend a large majority of their time talking about the characteristics, causes and reasons of their problems. A small proportion is devoted to proposing solutions, and a tiny amount to how they would like themselves or the world to be — a desired outcome. ACFC seeks to redress this imbalance.

We define a problem as: a difficulty the person does not like. Both criteria, ‘difficulty’ and ‘not like’, need to be involved.

There is a significant difference between the kind of problems a person describes if you start by asking, ‘What’s the problem?’ and the problems that arise when a person is contemplating realising their desired outcome.

The most efficient way we know of identifying the latter kind of problem is to support the client to establish and develop a desired outcome landscape and to wait and see what problems (if any) appear. When a problem appears which ‘interferes’ with a person constructing and maintaining the imaginary future they want, you can assume that how that happens in the session is symbolic (or a fractal) of what happens in their life outside.

ACFC aims to establish a desired outcome as quickly and respectfully as possible. The stated desire acts as a dynamic reference point against which the relevance of problems can be considered. Working with problems is first about acknowledging them, and secondly about when and how to attend to them — timing and context are everything.

What is a Remedy?

The first version of PRO was called PSO – Problem, Solution, Outcome. However we found that the world ‘solution’ brought with it associations that were contrary to what we were attempting to achieve; therefore we changed ‘solution’ to ‘remedy’.

Solutions and remedies have their place. If you’ve got a dripping tap – fix it. If you’re experiencing an acute pain – do something to relieve it. After a problem has been solved, remedied or cured, what remains? In a word, nothing. When the tap is fixed it works as before, there is no sign of change. When a headache disappears we may not even notice it has gone because there is only an absence. Remedies take away, reduce, remove, avoid, stop and counter problems. They give little clue about how the client would like the world to be after the remedy has been applied.[8]

We use ‘remedy’ as a shorthand for proposed remedy. The ‘proposed’ indicates that these are potential future remedies: solutions that have yet to be implemented rather than ones that have been (successfully) applied. And these remedies are the ones that to some degree clients needs help achieving.

Many of the important aspects of life are not like leaking taps that can be fixed or headaches that can be relieved. Gregory Bateson pointed out that we are making an error of logic when we use these kinds of simple physical remedies and metaphors for complex, abstract and on-going situations. Waging ‘wars’ on drugs, terror, crime, poverty, cancer or any other abstract noun are examples of political remedies that have major consequences for us all.

Ageing is another example. The cosmetic industry want people to regard ageing as a problem that can be remedied with anti-ageing cream, pills or surgery. But getting older is part of living. Sometimes it can be masked but it can’t be made to go away. An alternative approach is to ask: How would I like to age?

In the west we seem addicted to the notion that complex social and personal issues can be solved “once and for all”. After an accident or a failure of a system, how many times have you heard someone on TV declare “We must never let this happen again”. It’s an honourable aim but airplanes will continue to crash, people will continue to commit horrendous crimes and unexpected confluence of circumstances will continue to mean accidents will happen.

Many problems such as those arising from long-term relationships may not be solvable. Instead, a new kind of relationship needs to be evolved or created that can, in the words of Ken Wilber, “transcend and include” the previous problems. In ACFC the first step is to envisage the kind of relationship wanted.

This is not to say, ACFC is only useful for the ‘big’ issues of life. It can be used with highly practical desires too. Individuals have learned to arrive on time, parents to listen to their children, and groups devise a business plan.

The PRO model

It’s not for the facilitator to decide what they consider to be a problem, a proposed remedy or a desired outcome. The client’s language (and associated nonverbal expressions) is the arbiter. It can be a challenge for professionals trained in traditional diagnostic techniques to adopt this restriction. We have observed many sessions where facilitators spend much of the time focusing on what they consider is the central issue without taking into account what the client wants. The clues are always there but it takes a special kind of listening (i.e. modelling) to recognise them.

The table below summarises how to distinguish between a client Problem, Remedy or desired Outcome statement, and once identified Figure 3 depicts the Clean Language response that invites the client to attend to a desired outcome.

| PROBLEM | REMEDY | OUTCOME |

| DEFINITION A difficulty the person does not like. | A desire for a problem to not exist, to be reduced or avoided. | A desire for something new to exist. |

CRITERIA A difficulty in the present (even if the situation occurred in the past or will occur in the future). Contains a word or phrase indicating (or presupposing) the person does not like what is happening. No stated desire for anything to be different. |

Has yet to happen. References a problem. Contains a desire for the problem to change. Usually a desire for less of something [the problem]. Often includes a metaphor such as stop, lose, remove, get rid of, solve. Usually a variation of “I want not the [problem]”. |

Has yet to happen. Does not contain a clear reference to a problem. Contains a desire, want, would like, need for a new situation, state, ability, behaviour or knowledge i.e. to create or add something to them self or the world. |

| EXAMPLES I hate X. X will upset me. I don’t like X. (or, in the context, X can be presupposed to be problematic, e.g. “I am fed up.”) | I need to stop X. I want X to disappear. I would like X less often. I wish I could avoid X. I don’t want X. Please take X away. | I want Y. I want to Y. I would like Y to … I need more Y. I’d like to have Y. I wish I could Y. |

Figure 3

David Grove’s question, ‘And what would you like to have happen?’ is more permissive and less imposing than many equivalent starting questions, such as, ‘What do you want (to achieve)?’. It gives clients a lot of freedom to answer any way they would like, regardless of whether that is ‘well formed’ or SMART. We want the client to express themselves in their most natural way because this will reveal the background structure of their thinking – primariy to themselves and also to you.

Whatever the client’s response to the opening question, we recommend you first acknowldge whatever they ahve have said, exactly as they have sais it. Then you can following this with the apprpritate question depending on whether they have indicated they are attending to a Problem, Remedy or deisered Ouctome.

Notice that the PRO question ‘And when [Problem], what would you like to have happen?’ overtly acknowledges that there is a context which the client considers problematic, and then asks them to consider what they would like, given that the problem exists exactly as they have defined it. The facilitator makes no attempt to solve, reframe or in any way change the problem. Instead we trust the wisdom in the client’s system to discover what needs to happen to self-learn and evolve into taking appropriate next steps — or not. We do not presuppose that change is always the best option for a client, and we are open to them discovering they want something entirely different to what they had first thought.[9]

Notice also that the PRO question to a Remedy, does not include the client’s desire word. This is because we want the client to presuppose their proposed Remedy occurs, and then to consider what happens after that.

To summarise, Stage 1 is about using the client’s precise words to acknowledge and note problems and proposed remedies, and to facilitate them to identify a desired outcome as soon as it is appropriate to do so. When this happens the facilitator has a ‘contract’ to support the client to make the changes necessary to realise what they want. A desired outcome statement is our signal that the client is ready to move to Stage 2.

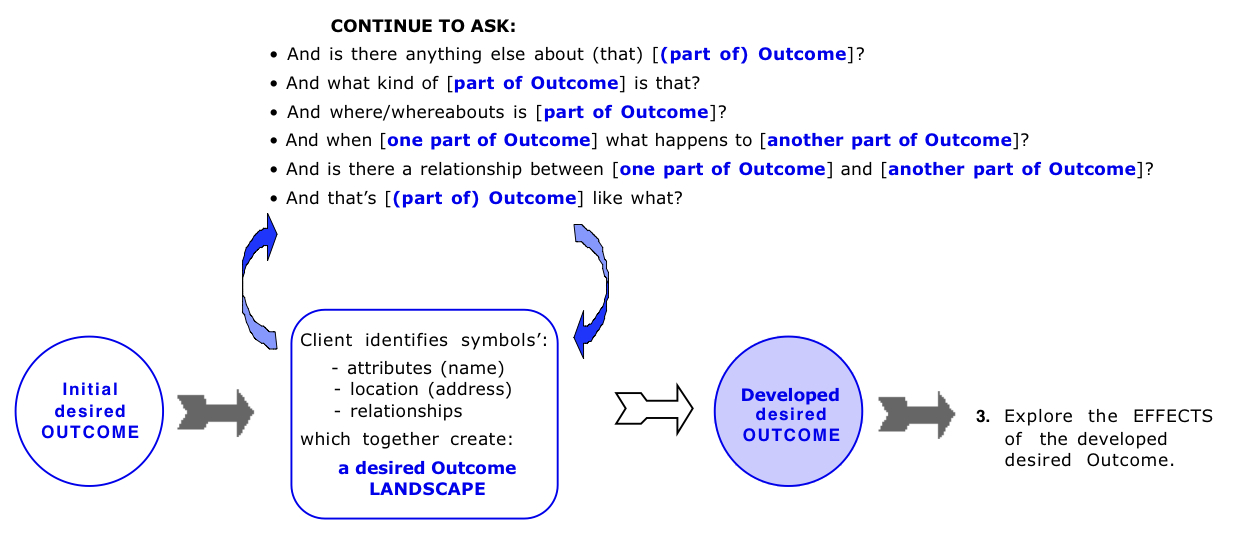

Stage 2 - Develop a desired outcome landscape

Once the client has identified a desired outcome, then what? Your job in Stage 2 is to nurture the client’s initial statement into a mind-body knowing — a three-dimensional embodied, psychoactive, metaphor landscape within and around them. David Grove called this process developing. The way to do this is outlined in Figure 4:

There are many benefits to developing a desired outcome from a statement into a rich mind-body experience. For example, attending to a desired outcome:

- Balances the tendency of many people to overly focus on problems.

- Goes beyond solving a problem.[10]

- Creates something to aspire to or aim for.

- Sets a direction for action and next steps.

- Is sometimes all a person needs to start to make changes in their life.

- ‘Provokes’ what inhibits the desired outcome from happening to make an appearance.

- Often spontaneously changes the relationship a person has with their problems.

Figure 4

Figure 4 How far the client gets towards fully developing a desired outcome landscape will depend on the complexity of the client’s system, the time available and the client’s reactions to their own perceptions.

A desired outcome landscape will not develop unless perceptual time is held still, and this is what developing questions do. A desired outcome statement will develop into a metaphor landscape as the client becomes aware of the symbolic nature of their experience.

As a landscape develops a number of things can happen:

| A show-stopping problem arises | >>> | Return to Stage 1 |

| A difficulty is encountered (which can be incorporated or noted and set aside) | >>> | Continue with Stage 2 |

| The client embodies their desired outcome happening | >>> | Move to Stage 3 |

| The client spontaneously starts to identify the conditions necessary for change | >>> | Follow client into Stage 4* |

| The client experiences a change | >>> | Jump to Stage 5 |

* You may need to return at some point to Stage 3 to check effects of their desired outcome happening.

When we say a ‘show-stopping problem’ arises we mean the client realises their desired outcome as currently conceived will not get them what they want, or not in the way they want, or the cost of achieving it is too high, or its not what they really want.

Sometimes a problem will surface which seems to have little to do with the desired outcome.[11] Unless the client indicates that working with the problem takes precedent over their current desired outcome then the problem can be acknowledged, noted, temporarily set aside and their attention returned to developing the original desired outcome landscape. If the client indicates they want to work with a problem, develop it for a short while before returning to Stage 1 to identify new desired outcome in relation to the problem. Notice, you may be using Stage 1 but you are not back to square one because both of you have updated information about the organisation of the client’s desired outcomes.

Generally, the desired outcome landscape is developed enough when one or more of the following occurs:

- Less and less new information about how the desired outcome is organised is described

- No new problems appear

- The client has identified the main aspects of their landscape and indicates they are satisfied with it

- The client’s attention spontaneously shifts to the effects of realising their desired outcome.

Stage 3 - Explore effects of desired outcome landscape

Stage 3 draws on the work of the erudite British biologist and systems thinker, Gregory Bateson, imported into NLP as ‘considering the ecology of the wider system’, i.e. exploring the effects of a client’s desired outcome happening. There are many ways to do this and we have devised a simple approach that uses only two clean questions (see Figure 5).

In Stage 3 the client is invited to imagine what will happen after their desired outcome is realised, especially in relation to the problems they previously described. And then to consider the effects of the effects, and the effects of the effects of the effects, and so on until the client has gone well beyond what they have considered before – both in terms of space and time.

Figure 5

As a result of exploring effects a number of things can happen:

| A show-stopping problem arises | >>> | Return to Stage 1 |

| A difficulty is encountered (which can be incorporated or noted and set aside) | >>> | Return to Stage 2 if desired outcome landscape needs updating, if not, continue with Stage 3 |

| The effects, and effects of the effects, etc. are explored without a problem | >>> | Ask client to specify the latest formulation of their desired outcome and then move on to Stage 4 |

| The client spontaneously starts to identify the conditions necessary for change | >>> | Follow client into Stage 4 |

| The client experiences a change | >>> | Jump to Stage 5 |

It is common that simply exploring effects will prompt a change. In fact the ‘boundary’ between exploring effects in Stage 3 and maturing changes in Stage 5 can happen so seamlessly that it is hard to say when one morphs into the other. At other times the client will report a distinct change which signals they are ready to move for Stage 5.

However, if a change does not spontaneously occur when transitioning to Stage 4 it is important the client has specified the latest formulation of their desired outcome before continuing. You request this by asking:

And when [recap desired outcome] what would you like to have happen now?

Stage 4 - identify necessary conditions

Should it be needed, Stage 4 makes use of one of the “strategic approaches” described in Metaphors in Mind – Approach E: Identifying conditions necessary for change. We chose this particular approach because it either:

provides a plan of what needs to happen

or

it helps to reveal any hidden logic which might act against the client’s desired outcome actually happening.

Identifying necessary conditions has proved to work particularly well with the kinds of issues client’s bring to coaching.

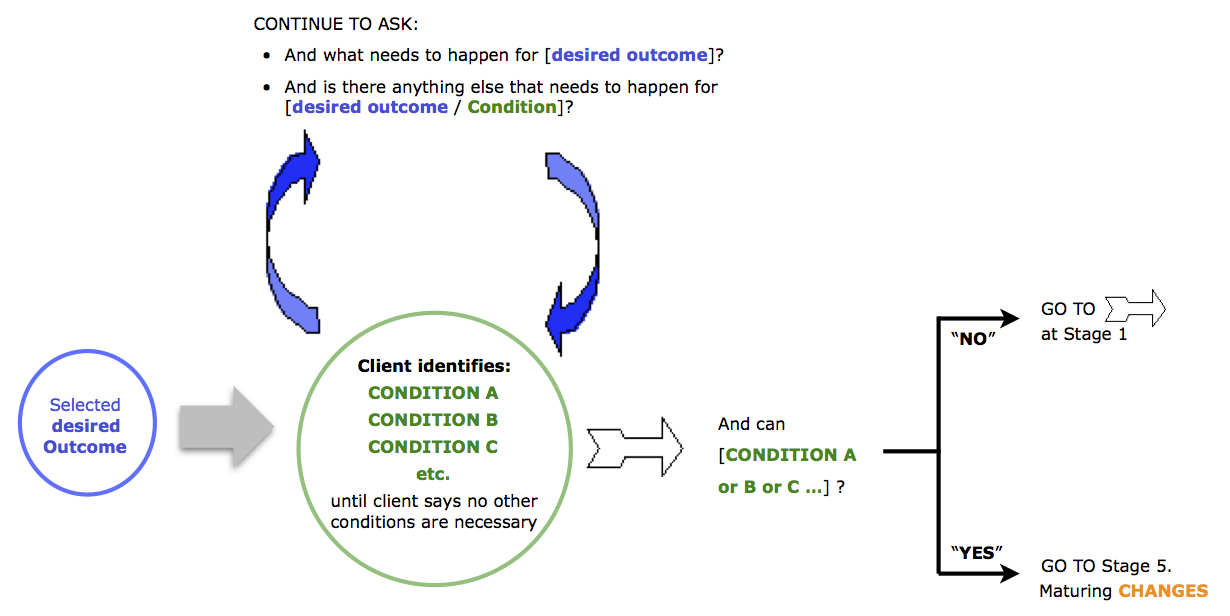

Stage 4 starts when having developed a desired outcome landscape and considered the effects, the client specifies what they would like to have happen now. Figures 6 shows how necessary condition are identified.

Figure 6

Figure 6 There is a distinction between ACFC and many traditional coaching methods. Rather than a client figuring out how to go from where they are to their goal — from A to B — the process charts a path from B to A using necessary conditions as the compass.

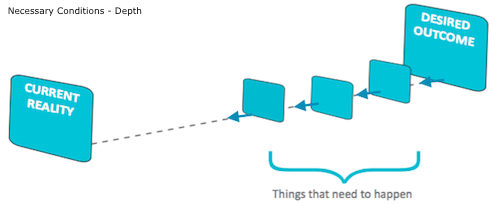

There are two ways to identify necessary conditions. Using Ken Wllber’s terminology, “And what needs to happen for …?” invites depth, while “And is there anything else that needs to happen for …” invites span, and these can be used in combination, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7[12]

It is important to ask the necessary conditions questions of a statement that is a desired outcome and not what you think would be good for them. The process will also cease to be clean and you may be leading the client if you work from animplied desired outcome.

e.g.

Not clean (Leading):

| Client: | It would be good for me to speak up for myself. |

| Facilitator: | And what needs to happen for you to speak up for yourself? |

Clean:

| Client: | It would be good for me to speak up for myself. |

| Facilitator: | And when it would be good for you to speak up for yourself, what would you like to have happen? |

| Client: | First I need to have the confidence. |

| Facilitator: | And what needs to happen for you to have that confidence? |

In the first example there is no stated desire for the outcome, in the second the word ‘need’ provides the permission to ask the ‘And what needs to happen for …?’ question. And while it is quite possible that the client would have arrived at the same conclusion by either route, asking the extra questions ensures it is their desire that sets the direction, and they know that.

There is a good example of identifying necessary conditions in the video: A Strange and Strong Sensation. [Annotated transcript available as PDF to download.]

Once conditions have been identified the information can be utilised in a number of ways. Three of the more common are to identify:

a. The first condition that needs to be fulfilled for the client to start the journey towards their desired outcome. Often this can be traced back to a specific behaviour or decision the client can do — if they want (i.e. it is up to them).

b. The most salient condition, the one on which many of the other conditions depend.[13]

c. Any inherent logic within the conditions which is problematic, e.g. the client says one or more of the essential conditions cannot or will not be met; circularities or paradox are involved; there are so many conditions the likelihood of fulfilling them all becomes diminishingly small.

When the first or most salient condition is identified, the necessary conditions process can be repeated at finer and finer detail, often ending at the client’s symbolic model of the embodiment of the decision to act (or not). It is enough to facilitate them to attend to (and stay at) the moment just before the decision. It is especially important the facilitator remains neutral; what the client does is up to them and often that will happen after the session. Whatever they do (or do not do), they will do it with a far greater degree of awareness of their own agency, and that will have an effect on their system.

In cases of problematic logic the facilitator’s responses is:

And when [problematic logic], what would you like to have happen?

Depending on the client’s response, the session may be concluded or they may need to take a trip through the whole ACFC process again, or anywhere in between.

However, in most cases facilitating the client to self-model the conditions necessary for change to occur will be enough for the system to start changing — the cue to transition to Stage 5.

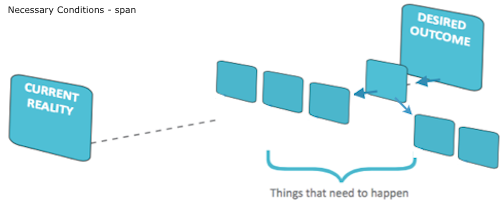

Stage 5 - Mature changes

Figure 8

Maturing has many purposes:

First, it offers the client’s system the opportunity to consolidate the changed landscape. In this way the client gets to know how the newly configured landscape can form new self-sustaining patterns. This takes time. We marveled at how David Grove could spend a third of the session maturing changes.

Second, maturing checks if the new landscape is robust enough to handle the problematic conditions previously mentioned by the client.

Third, maturing checks that the change is appropriate for the ecology of the client’s system. It gives the client’s system the chance to ‘object’ to the change by raising doubts, concerns, fears and other problems.

Fourth, while the first three are happening the client is simultaneously rehearsing making use of the new metaphors. Later this can be extended into rehearsing real-life situations which the client previously found problematic.

Fifth, maturing often sets a direction for changes in the days, weeks and months after the session.

As a result of maturing, one of three things happen:

| The changed landscape is consolidated into a resource which can handle the previous problems | >>> | Finish the session |

| An existing problem prevents or counters the change | >>> | Return to Stage 1 |

| A new problem emerges | >>> | Return to Stage 1 |

After a change, although the previous neural pathways still exist (and may be useful somewhere, some when), maturing a new pattern can become the behaviour of choice. And when that behaviour continues for long enough the new pattern becomes familiar and a natural way of being.

3. Anything else?

When nothing changes

If after journeying through ACFC the client has not experienced a shift, or enough of a shift for them to be ready to make a change in their life, two of the most valuable approaches are to:

a. Wait and see what effect the session actually has since surprisingly valuable changes can occur over the coming days and nights, even when the client was not expecting them.

b. Make use of the resources that have appeared in the client’s landscape.

Developing resources

A resource can be anything that the client values or proves to be useful. They can spontaneously appear in stages 2, 3, 4 or 5. A desired outcome is itself a kind of resource – especially when it is embodied. Like desired outcomes, resources can be developed and their effects on the rest of the landscape explored.

If you look for ‘resource’ in the index of Metaphors in Mind you will see how to notice overt and latent resources, how to bring them into the foreground of the client’s awareness, and examples of how resources can be utilised. In summary the process is:

- Identify (potential) resource.[15]

- Develop qualities of the resource (metaphor, location, attributes, function).

- Explore effects of resource, by asking:

-

- And when [resource], then what happens?

- And when [resource], what happens to [desired outcome or problematic context]?

- Mature changes as they occur.

Many people do not know how to access their own resources or do not do it often enough, and developing resources is therefore almost universally valuable. However, even when we facilitate a client to develop and explore the effects of a resource we are still not trying to change anything. If the client’s system remains unaffected then something important is happening and that is what we would invite the client to attend to next time.

When ACFC is not enough

Although A Clean Framework for Change works for most people most of the time, it doesn’t work for everyone all the time. No process will do that. You might be thinking, why wouldn’t a person who wants to improve their life identify a desire, construct an experience of that desire happening and what effect it will have, and then figure out what needs to happen for their desired outcome to become a reality? One reason is because they just can’t. It is not that they are incapable, it is that one or more aspects of their system reacts against the very idea. Even considering the possibility provokes a counter response.

There are different indicators that the organisation of the client’s system is not responding to ACFC at each of the five stages:

If after considerable skill, patience and modelling by the facilitator —

| Stage 1 | The client cannot identify a desired outcome. |

| Stage 2 | The client cannot develop a rich description of a desired outcome or keep their attention on their desired outcome. |

| Stage 3 | The effects of the desired outcome happening are unacceptable to the client or to some part of their system (including their perception of others and the environment). |

| Stage 4 | The client cannot identify the conditions under which the desired outcome can be realised. Or, a binding logic prevents the conditions necessary for change from being enacted. |

| Stage 5 | The maturing of a change is interrupted by a problem, concern or doubt which cannot be resolved by continuing with A Clean Framework for Change. |

The best way to find out if any of the above apply is to give the client multiple opportunities to: identify a desired outcome; develop it into a desired outcome (metaphor) landscape; explore the effects of that outcome happening; identify the conditions necessary for the desired outcome to become an actual outcome; and to mature any changes as they happen.

We have seen numerous facilitators say their client can’t get a desired outcome when in fact the facilitator missed a desired outcome statement the client had given them. This is often because (a) the desire was embedded in the middle of a lot of other non-outcome information and the facilitator stopped determining whether every statement indicated a problem, a proposed remedy or desired outcome; or (b) once the session is underway, the facilitator missed opportunities to use the PRO Model.

When going through the stages, if the client encounters an obstacle, problem or a ‘What if?,’ this is not an indication that ACFC is not working – quite the opposite. It is working perfectly because the process is designed to uncover the specific problems that inhibit the client making the changes they say they want. These problems are usually of a quite different character from the kinds of problems that would be described if the client had been asked at the beginning ‘What’s the problem?’.

Sometimes, a client concludes that what they would like to have happen either isn’t going to happen, or it wouldn’t be a good idea if it did. Of course, that realisation is a change. Mature this change as usual and at an appropriate moment ask, ‘And given […], now what would you like to have happen?’.

When we say ACFC is ‘not enough’ we mean that after several iterations it becomes clear applying ACFC to problems that arise does not produce a desired change. This usually indicates that the client is in a bind — a unwanted repetitive self-preserving pattern.[16]

Even in the presence of a binding pattern, ACFC still has its uses. It will work with straightforward binds although you may need to iterate through the stages a few times before all the strands of the bind are untangled.

While a client is focusing on aspects of their bind you are looking for opportunities to ask ‘And when [recap binding pattern], what would [you/symbol] like to have happen?’. Asked at an appropriate moment this question brings the client face to face with the whole pattern and then invites them to identify a desired outcome for how they would like to respond to experiencing a bind. They are unlikely to have ever been asked this question before and it may need to be repeated several times before the client grasps its significance.

On the rare occasions where this approach is ineffective, noticing how it doesn’t work turns ACFC into a sophisticated diagnostic. The process by which the client’s system rejects, counters, diverts or otherwise avoids going through the five stages can be taken as a signpost to what Ernest Rossi called The Symptom Path to Enlightenment. The stage that prompts the response and the means by which the response occurs is exactly where the client needs to focus their attention.

Achieving what you want

While we have described ACFC as a process for facilitating others to make changes in their life, it can also be considered as a general-purpose model for self-facilitated development. Once you embody the process of noticing what you want, elaborating that desire, considering the effects of getting it, working out what needs to happen for you to achieve that, and following through on the changes that occur, you are well on the way to being a success in our goal-orientated society. And the formula works just as well with less tangible desires, say discussing with your partner the kind of relationship you both would like.

Making ACFC work for yourself is not a one-time process. The key is to keep using it to adjust what you do in response to what actually happens, your changing needs and wants, and the problems or opportunities that arise.

If after diligently applying ACFC to an important desire in your life without getting the result you want, you might consider whether you are deceiving yourself. If so, you might need to learn how to act from what you know to be true before you can make the changes you want – but that’s another story.[17]

Concluding thoughts

You will not get the most from ACFC if you use it like a linear technique that you guide a client through step-by-step. The key is to use ACFC as a modelling methodology and as a high-level aid to facilitating the client’s unfolding journey. To do both of these well you will need to keep adjusting what you do in response to what actually happens – every step of the way.

Footnotes

1 James Lawley & Judy Rees (Jun 2011) Theoretical Underpinnings of Symbolic Modelling v3 [Download PDF].

2 James Lawley (Aug 2007) The Neurobiology of Space.

3 James Lawley & Penny Tompkins (Jun 2008) Maximising Serendipity: The art of recognising and fostering unexpected potential – A Systemic Approach to Change.

4 James Lawley & Penny Tompkins, A Model of Musing: The Message in a Metaphor, Anchor Point Vol. 16, No. 5, May 2002.

5 Penny Tompkins and James Lawley, Coaching for P.R.O’s, Coach the Coach, Feb. 2006.

6 Charles Faulkner, The World Within a Word (Audio tape set), Genesis II, Lyons CO, 1999.

7 More formally, a desired outcome is a state of being that has four aspects (PPRC):

- A perceiver of the desired outcome that knows the desire exists. This can be a person, an aspect of a person, a group of people or any sentient being. And in the land of metaphor any symbol with agency can have a desired outcome.

- A perceived – how the world will be if the desired outcome happens – the outcome part of the desire.

- A relationship between perceiver and perceived. By definition this will be some form of want, wish, yearn for, craving, fancy, impulse – anything that expresses the desire.

- A context within which the desired outcome has significance for the perceiver.

See Penny Tompkins & James Lawley (Feb 2006) Paying attention to what they’re paying attention to: The PPRC Model.

8 While the distinction between a desired outcome and a remedy often coincides with the NLP metaprogram distinction of ‘towards goals’ and ‘away from problems’ and the NLP well-formedness distinction of ‘stated in the positive’ and ‘stated in the negative’ it is not identical to either. For example “I want to find my lost self” would be regarded as towards a goal and stated in the positive, while in the PRO model it is classified as a remedy to a problem.

9 A key feature of the PRO model, particularly useful when it is being used outside of a coaching session (e.g. by managers, teachers, parents, etc.) is the understanding that problem statements do not contain a desire for anything to be different. They are simply a statement of the person’s experience, they do not require any response, except perhaps to acknowledge the person has a problem. If parents, teachers, and managers etc. train themselves to not image people want to change a problem when they have not specifically said so, it can transform their most important relationships. For example, a teenager says to their parent “I am fed up you bossing me about”. For sure, this is a problem for the teenager, but they have not said they would like it to be different. If the parent feels it is their job to solve problems they may well respond to this by proposing some kind of solution (probably exacerbating the adolescent’s problem!). Whereas, a ‘cleanish’ conversational response would be “OK, you’re fed up with me bossing you about. And given you are fed up like that, is there anything you want?”

10 Identifying a desired outcome and developing it in Stage 2 can have a similar effect to the Solution Focus “miracle question”: “Suppose that one night, while you are asleep, there is a miracle and the problem that brought you here is solved. However, because you are asleep you don’t know that the miracle has already happened. When you wake up in the morning, what will be different that will tell you that the miracle has taken place?” The Solutions Focus: Making Coaching and Change SIMPLE. Paul Z Jackson and Mark McKergow (2006). However, a key difference is that with A Clean Framework the client does not have to “suppose” that all his or her problems have disappeared.

11 To check the relevance of a newly surfaced problem to the original desired outcome you can ask ‘And is there a relationship between [new problem] and [desired outcome]?’.

12 Diagram modified from Marian Way, Clean Approaches for Coaches, p. 156.

13 Penny Tompkins & James Lawley (Feb 2009) Attending to Salience.

14 The processes of developing, evolving and spreading a change might seem familiar since they are exactly the same as the processes used in Stages 1 to 3 but used for a different purpose:

| Stages 1 – 3 | Stage 5 | |

| Identify desired outcome | ≡ | Notice change has happened |

| Develop desired outcome | ≡ | Develop what has changed |

| Explore effects over time and space | ≡ | Evolve change over time and discover whether change spreads to other areas |

There is only one difference. Stages 1 to 3 happen before a change has occurred and Stage 5 happens after. In terms of process, the questions you ask are identical. In terms of the client’s perception the difference seems like night and day.

15 An optional extra is to identify the source of a resource by iteratively asking ‘And where could [resource] come from?’ several times if necessary, and then utilise the source of the resource which is usually even more resourceful than the original resource.

16 How we work with binds and double binds is described in James Lawley, Modelling the Structure of Binds and Double Binds Rapport 47, Spring 2000, and in Chapter 8 of Metaphors in Mind. Also watch the video: When science and spirituality have a beer.

17 James Lawley and Penny Tompkins (Feb 2004) Part 1- Self-Deception, Self-Delusion and Self-Denial, and Penny Tompkins & James Lawley (Apr 2004) Part 2 – Learning to Act from What You Know to be True.